We love artists at The Wild Word.

Our Artist-in-Residence page provides a space for artists to showcase their work and to spread their creative wings. In their month of residency, invited artists are encouraged to collaborate with other contributors within the magazine, to experiment and develop new projects, while giving us an insight into their creative process.

Our IS ANYBODY OUT THERE? Artist-in-Residence is the writer and artist Donna Steiner.

Inquiries about purchasing the paintings may be made directly to the artist. Please write to her at donna.steiner@oswego.edu.

Second Art

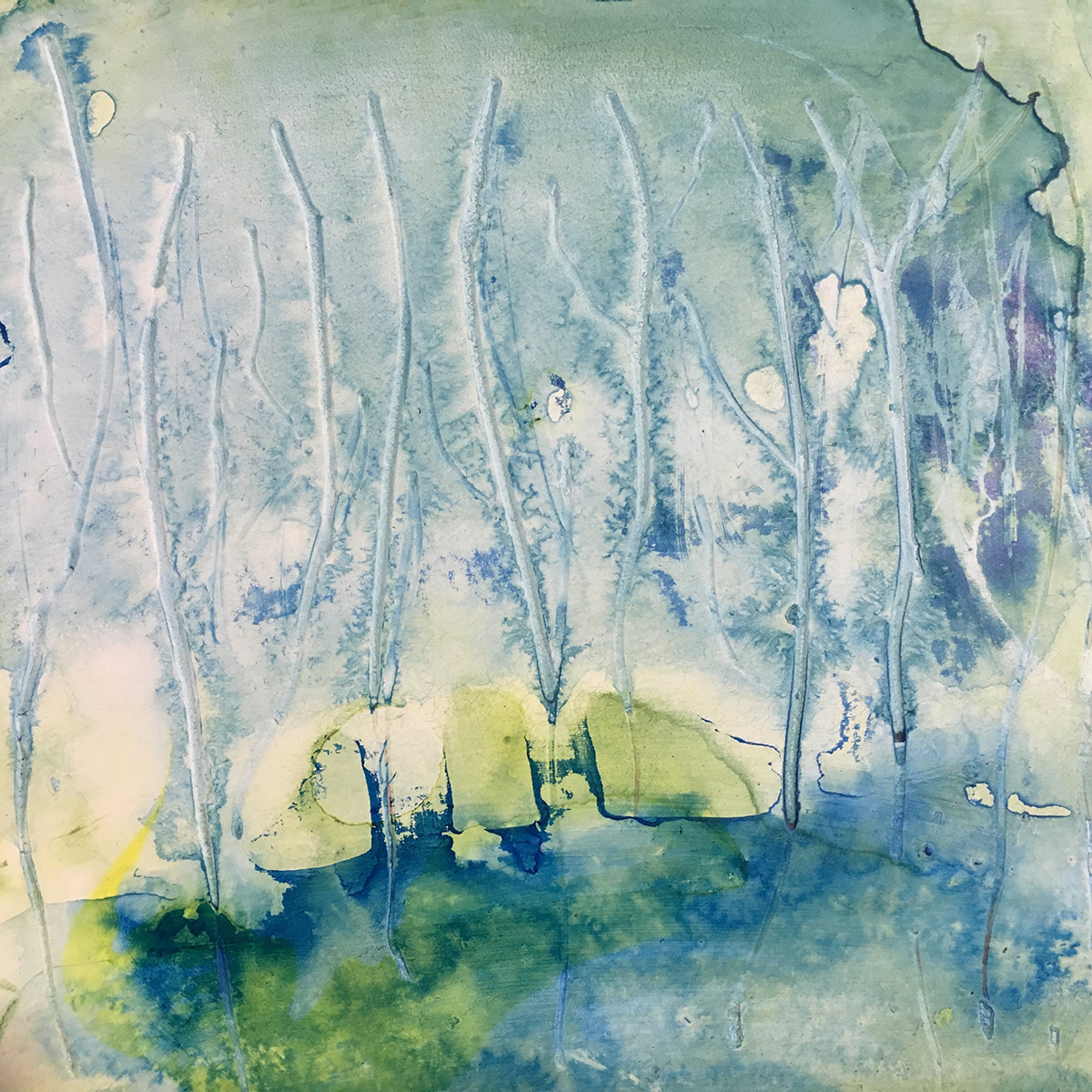

Not writing, or writing very little, was not acceptable; there was energy in my body that required expression. A wise and generous friend invited me to her studio and set me up with a big table and art supplies. “Make something,” she said. I started wrapping thread around branches, building small, broken, half-mended creatures.

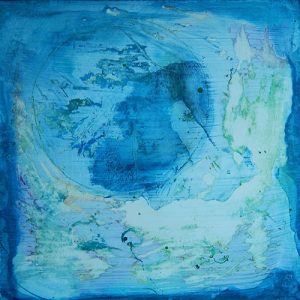

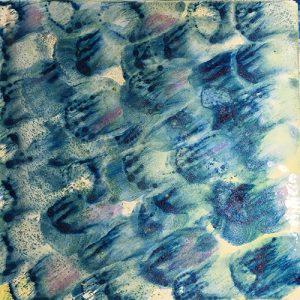

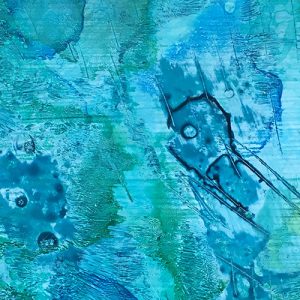

Weeks later, when I ran out of branches, on a day when I felt brave, I started brushing water and ink on clayboard. To me these were maps of the ocean, where my parents live now, and I painted blues and greens exclusively for many months. Most of the paintings were abstractions, but occasionally I scratched the outline of a squid or a fish into the surface of the board. I was creating a world for my parents, a home, and finding ways to communicate the magnitude of the loss.

When I was in the studio, time collapsed, sound collapsed, anxiety disappeared, grief abated. All that mattered was the physicality of standing at the elevated table, watching one color bleed into another. The ink was appropriate – my mother was a frustrated writer, my father an amateur painter. Both of them were master letter writers. Dissolving ink into water also felt significant. Not only had my parents’ bodies been cremated and their ashes released into the Atlantic Ocean, but the beach was our childhood home away from home; we grew up on the Jersey shore and there is still no place I would rather be.

My work in the studio engaged me when nothing else did. Painting became my second art.

There is tremendous freedom and comfort in not being expected to do something “right.” In learning a new art, I feel none of the pressure of convention, can relax into the process and move with abandon. That is not to say my studio time is frivolous, for although there are elements of play, my work there is intentional and intellectually engaging.

There is satisfaction in abstraction, in allowing the materials to tell stories that I cannot tell with words. There is pleasure in creating beauty, in observing the chemistry of paint and water and heat and gravity. There is control and absence of control, and confronting that dichotomy is cathartic. When I scratch the surface, actually use tools to cut the surface of the clayboard, it is also metaphoric – I am scratching the surface of emotion, of the body, trying to release something that has no other release.

And there is the discipline of patience – I literally watch paint dry. I watch particulates attract or repel the substrate, I watch ink gravitate to a corner that is microscopically lower in elevation than the rest of the board.

In my second art, everything has an irrevocable impact. If I choose to alter a painted surface, I have to say goodbye to what is in front of me. There is no way to get it back.

That is a lesson that I need to learn every day. There is no way to get it back.

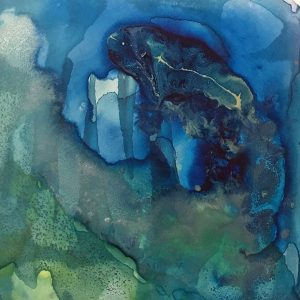

Below the Surface

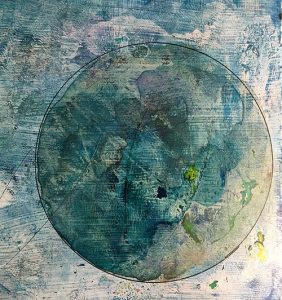

Perhaps making the globes look old evokes a sense of loss. We’re living in a time where, for many of us, things that once felt familiar, even reliable, now seem jeopardized. Perhaps we have always lived in a world that holds its secrets below the surface.

What interests me is creating and erasing simultaneously. It sounds very basic, but there is something about this negotiation that feels necessary and instructive. The effort of physically scraping a layer of “skin” off a painting leaves my fingertips sore, leaves the tools of this effort torn but elegant, and allows me to contemplate how to create in an era of perceived diminishment or destruction.

Making art is inherently hopeful to me—“practicing hope,” in effect, is built into my process. And I think I am drawn to things that feel incomplete, or even broken or damaged. My paintings feel like that to me—there are gaps, there are reductions, there are places that feel undone or exposed or hidden. Maybe those gaps, those real or metaphorical spaces, are places for someone else to enter the work. It’s like clearing a space on a park bench for someone else to sit. It’s like opening up an old map and saying come on, let’s figure out where we’re going.

Winter (Color Hunger)

There are days when visibility is more a concept than an actuality, days when I may not see another human being.

Actual view out my apartment window, during snowstorm.

My friends are the pigeons who perch on the neighboring church, the school crossing guard I see walking to her post in the dark hours of the morning, the snow plow drivers who clear the road.

When going outdoors is a poor option, I work inside. I write, I paint, I photograph the paintings. I photograph the inside of my apartment, close-ups that become almost abstract, images that look like they are on the verge of either disintegrating or coalescing.

During the winter, when the sky is gray with heavy clouds and just about every surface is white with snow, I crave color. It’s like craving fruit or Vitamin D – I NEED color.

I bought this pomegranate just so I could see the color.

Although most of my recent work sticks to a blue and green palette, in winter I experiment with yellows and oranges. I leave those bottles of ink out so my eyes can soak up their light. It is a little like sun bathing.

And if the colors I find are not enough to warm me, I wrap myself in the brightest blanket I can find and wait until new words come, or new images, or – if I am lucky – the sun itself makes an appearance.

Is Anybody Out There?

Look at the lower right quadrant – a little white skeleton…

I loved reading the poems in this issue of The Wild Word. There are ghosts and aliens, there is an intergalactic language with “some interesting alphabet sounds.” How can we resist not speculating about other dimensions, other lives, how can we resist revisiting concepts or beliefs we’ve long held as fact?

I wonder if the very acts of speculating and imagining are more important now than ever, as we witness growing intolerance of anything perceived as “other,” as “alien,” as Not Exactly Like Me.

Maybe that’s something this second art has given me—a deeper sense of opening, of consideration. Whether making marks on paper or on a screen, or using a paintbrush to swirl ink, or a camera to shift or freshen or refine an image, when I physically handle the materials and tools of these arts I am closer to what matters.

It can seem, quite acutely, for those of us attempting to share creative work, that nobody is listening, nobody is noticing, nobody is out there. Submitting one’s writing or putting one’s art out there – isn’t that what we literally say to each other– “you’ve got to put it out there” – can feel like exercises in futility. But when the world itself seems precariously tilted, when loss is a tidal wave of grief, when joy – yes, joy – falls on my shoulders as lightly as a bed sheet wafting down, I am so lucky to have a set of brushes and pens, I am so lucky to have friends who say “make something.” I am so lucky to have an ocean of memories, and time, and faith.