We love artists at The Wild Word.

Our Artist-in-Residence page provides a space for artists to showcase their work and to spread their creative wings. In their month of residency, invited artists are encouraged to collaborate with other contributors within the magazine, to experiment and develop new projects, while giving us an insight into their creative process.

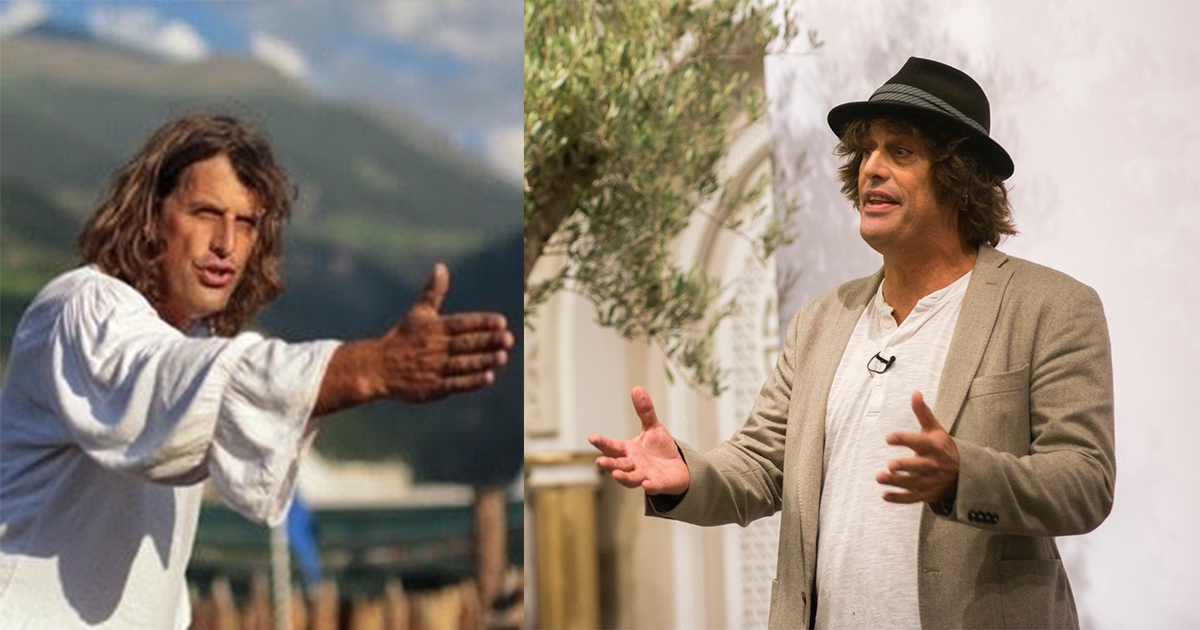

Our AND SO WE LOVE Artist-in-Residence is the storyteller and writer Christian Rogers.

Where Waters Meet

The soundtrack to my childhood was the sea. My bedroom was just a short two-minute run down to a beach at the edge of the Atlantic ocean. I grew up listening to the songs of the tidal changes, the waves crashing against the rocks discharging their energies onto the shore, and the soft, smooth, swish of water rolling over the sand. The sea was playing a permanent push-me-pull-you game with the coast. Its rhythm was persistent and undeniable.

The land had an uneasy pact with the ocean. A restless peace that I shared with it then and still do today.

It is said that if you listen to and remember what the sea tells you, then you will always come back to it. I can only agree.

We moved a lot. My parents were, and still are, restless people. We were living in London when my mother decided to take us back to the sea and so I grew up in North Devon. I was very lucky.

A large and very bustling stream ran down to the sea near our home. It fascinated me and I came home wet from it many a time. I would follow it back up the hills as far as I dared looking for its secrets. It flowed in and out of sight, under and above the ground with a steady and continuous self-assured flow. It knew what it was about, that stream, as it wound its way down to the place where, tumbling over the debris of a cut in the cliffs, it became part of the sea. This was Watersmeet.

Every stream or river rises somewhere. Ours rose on the edge of Exmoor, a wild beautiful place. I would imagine its journey from the source flowing along, gathering strength and vigour, growing deeper and more grown up. All the time picking up energy and material from the places it passed. Then it would flow into the great ocean and become part of a greater story.

In this place, where I grew up, I became restless too… Then I left.

I have made many mistakes, got loads of things wrong and messed up often. I tried my hand at so many different jobs. I was always uneasy. At the time I had the belief that there was no such thing as a bad experience. Which is true. I was looking. Searching.

I discovered juggling. Here was something for an uneasy spirit.

I began performing in Wales as a street performer in 1986. It was a way to make a living and one that I could do on my terms. No boss, no rules. I had developed, by that time, a healthy allergy to institutions and the political state of Britain at that time was depressing and restrictive, the state, particularly the police, didn’t like people like me very much, so I left to travel, alone, through Europe. I lived only from what I could earn on the streets as a clown and a juggler. I went to each corner of Europe as it was then, meeting travellers, vagabonds and crazy people from all around the world. I learnt to accept people as they were just as they were accepting me as I was. I learnt tolerance. It was a revelation. I learnt not to judge people too quickly either.

Along the way I absorbed much from the cultures that I encountered. Like how a stream is losing its old identity as it flows to the sea, creating a new one by picking up stuff along the way. I was driven by curiosity and an overwhelming desire to look round the next corner. My restlessness was being useful.

The more I traveled the more I learned about people. I became aware that everybody had stories to tell. These stories piqued my curiosity. Then I discovered folk tales from a peasant farmer in the Pyrenees. His name was Jacketas and he was a goatherd. He had the most amazing azure eyes. He had lived in the same house, as far up as was possible at the head of a valley, tending goats for over eighty years. Only once in his life had he been out of the valley and seen the nearest town. I loved him. There were a few others, mostly German, “freaks” like us living nearby, and between us we could translate his language into one that we could all understand. I had to learn Spanish pretty quickly.

The importance of culture and, especially, language as means of preserving identity is vital. I became fascinated by folk tales and their role in keeping culture alive. I began to delve deeper into them and discovered how entertaining and effective a simple tale could be. As a traveler bound to traveling lightly, I found in stories the perfect material for my shows. Performing a mixture of tales and anecdotes using juggling, physical comedy and marionettes that I made out of materials I found on the streets I created a self-contained entertainment that could be performed anywhere. Therefore I could live anywhere I chose.

I am still restless. Like the stream I have gathered strength and vigour, become deeper and more grown up while flowing through life. Like the stream I have picked up energy and material from the places I have passed through. These places, the people I have known remain with me still and often when I am telling my stories they return to me in my mind to become part of the tale. The listener will not know this, but he or she will hear it. To know this is a wonderful pleasure for me.

Now I work full-time as a professional storyteller in schools, for consulting agencies and management coaching projects, as well as being the official storyteller to the Vapiano chain of restaurants. I run workshops, I teach performance and communication skills to anyone who is keen enough to want them. I am bringing the skills that I have learned on the streets and in the theatres of the world, in my life, into classrooms.

But first and foremost I am a storyteller. I have over three hundred and fifty of them in my head. Tales from all over the world. Tales that confirm the power of humanity and offer promise to the downtrodden and weak. These stories have empowered humans for millennia and they are as persistent and undeniable as the rhythm of the oceans.

In India, according to Salman Rushdie, they say all stories flow into a great ocean. The sea of stories. They too have picked up strength, vigour and energy on their way there.

I remember, often, the child who got soaked in the stream while searching for secrets at Watersmeet and now, understanding more about what I do, I am aware of the privilege it is to be who I am.

The Sadhu

There was once a King who ruled a land in the cold north. He was a hard man with an iron will and people feared his rule.

He was not only hard but he was also cruel and he would think nothing of punishing anyone who offended him by taking their lives and he enjoyed thinking up new ways of doing so.

One day he was walking with his dog along the banks of the lake upon which he had built his palace. It was early winter and on the lake there were already small patches of ice forming on the surface of the water.

He walked along throwing a stick, which his dog, with a yelp and a wag of the tail, would run off to retrieve. The king liked to do this. It seemed so pointless an exercise to him, which made a change from all the other things he had to do as the king of a great country. As he came closer to the lake he threw the stick into the water but instead of jumping in after it, as he usually did, the dog stood barking towards the place where the stick had landed. Her master caught up with the dog and encouraged her to go in but each time she put a paw in the water she pulled back from the edge and just stood there whining. The king wondered why this was. Perhaps the water was too cold. The king took off one of his boots and dipped his foot into the water, then he swiftly removed it. The water was very, very cold. So the stick remained where it was and he and his dog returned to the palace.

That evening, as he sat by the fire looking out across the lake he began to wonder about how cold the water was. How did the dog know that it would be too cold to swim in? How long would she have survived for had she have jumped in? These questions kept him awake long into the night until he decided that he had to find the answers. He was a king and therefore must know everything.

But how could he find out? He could just get a slave perhaps, or a prisoner, and throw them into the water. He had such cruel thoughts. But that just seemed too easy. No, he felt a bit of sport was to be had here. He had a clever idea.

The next day, all around the country, in every town, large notices appeared stuck to the walls stating that the king was to have a competition. A challenge. Anybody who could spend twenty-four hours standing up to their necks in the water of the lake without anything to keep them warm as they did so would gain anything that they should ask of him. The king knew very well that no human being could survive so long in the almost frozen water so he was sure that he would not have to honour his part of the deal. This was how he would find out how long anyone could survive in the water.

The date for the challenge was set.

Many young men came. Some poor, some rich. Some idle in search of quick riches, others stupid but brave. People gathered at the lake in front of the palace to see the spectacle.

The king sat up on his balcony to watch the proceedings and one by one the hopeful and foolhardy men went down to the lake. They stripped off and stepped into the water. Up to their necks they stood. Some managed to remain in the water for twenty minutes or more before, half frozen themselves, they had to be dragged out by the ropes that were tied to their ankles. Most gave up after just a few minutes. The king was disappointed.

But when the crowds had left, a young Sadhu appeared at the lakeside. He looked up at the king and announced that he would try to stand in the water for as long as the king had stated on his notices. The Sadhu was so thin and looked so weak that the king could not imagine that he would succeed but he waved a hand to the young man and told him to try and that he should not forget that he was allowed nothing to keep him warm. The king sat down again to watch.

The young man stepped into the lake, showing no expression as he did so. He went out to a place where the water was deep enough to cover his shoulders and then he stood very still. He looked serene and peaceful as he stared ahead of him up at the balcony where the king sat. Even after an hour his expression had not changed. He was used to hardships and discipline. He knew how to slow his heartbeat down so his breathing became almost imperceptible. The king watched him even more intently as the time passed. The hours passed.

The evening came and darkness began to fall. Still the young man stood stock still in the water, his face wearing the same expression of serenity. He stared up to where the king was sitting even though he could no longer see him clearly for, although the moon was full and strong, the king sat in the shadows. But he was there, very intently watching the mad man in the water who did not move. He could see him very clearly and began to wonder about the young Sadhu.

The water was much colder now, but he had slowed his heartbeat down so much that he did not feel the difference. Time meant nothing to him. He was going to stay where he was until he was no longer able do so. As the night drew on he began to drift further into himself. Deeper into his mind. He knew that if he could control that then he could control his body. Had he been less aware of this and more of what was around him he would have noticed little slithers of ice floating around him. One even bumped into his back but he had lost his sense of feeling long ago and was no longer in his body. He had stepped out of it and his existence was now purely in his mind. His eyes were the only part of his body that connected him to the world. They stared ahead without blinking.

Tiredness played no part in this. He had done many things in his life that had pushed him to his limits. He had no idea of how long he had been in the water or how long he still had left to go.

But the water was getting colder and his will, like his strength, was beginning to fade.

Then a small, flickering light appeared in a window. The Sadhu’s gaze turned slightly toward it. Someone had put a candle on the ledge of a window in a room near to the king’s balcony. Now he kept his gaze fixed on this light. In the glow coming from the candle his eyes saw a face. A soft and beautiful face. This was the face of the king’s own daughter and she too had been watching the young man in the water.

Now she had lit a candle as a sign to him that he was not alone.

He became aware of her as he saw that she was watching him. His willpower began to stir back to life. He could see in her expression that she had a great compassion for his plight and it came to him that she would remain there at the window as long he remained in the water. She was willing him to stay alive.

So, instead of weakening he grew stronger. His breathing, still almost unapparent, grew steadier as he turned his eyes away from her face and stared into the bloom of the candle.

When morning came he was still alive. Still standing up to his chin in the cold, almost frozen water of the lake. The twenty-four hours had passed. As the guards pulled him out, the young man was unable to move so they had to carry him up to the palace. As they did so the king, from his balcony, heard the crowd, which had returned to see this marvellous feat. They were cheering for the Sadhu and he realised that he would now have to keep his part of the bargain. This worried him. What would the young man ask of him?

The king began to think of ways to get out of the deal.

At first they wrapped the young man in blankets and then very slowly they warmed him up using tepid, and then gradually warmer, water. After a few hours they put him near a small fire and then, towards evening, he was able to move and to speak. The King, begrudgingly, congratulated him and wondered how he had managed to stay alive for so long in the icy lake.

Slowly the Sadhu explained about his breathing and the importance of discipline. How he had learnt to master his own body and to control his willpower. He then told the king about how, just as he was beginning to lose his will to live, a candle had appeared on the window ledge.

At this the king clapped his hands and shouted out.

“Hah! I told you that you may not have anything to warm you. Nothing to aid you. But you had a candle. Someone brought you a candle that must have kept you warm. The deal is over!”

Relieved to have found a way to get out of the bargain he gave the Sadhu no further chance to speak and ordered the palace guards to throw the young man into the prison. This was done and the king was spared having to reward the poor Sadhu with any of his own riches.

Some days later, the king was sitting at his breakfast table. He saw that his daughter had not joined him and he asked the servants where she was but none of them could answer him. She had not been seen for a while.

When he did not see her that evening the King began to get concerned. That night he went to her rooms but she was not there. She was nowhere to be found. Now he began to worry.

The next morning the King rode away on his horse and began to search for her. He travelled along the coast and through the mountains. He followed every track in the forests. He stopped in all the villages along the way to search the houses. Wherever he went he asked about her but nobody had seen the princess. Finally, after more than a week of searching, he gave up and turned his horse in the direction of the palace.

It was late when, entering the wood that surrounded his home, he saw a light to the side of the road. He stopped his horse and got down to take a closer look. He pushed his way through the bushes and came into a clearing.

He saw her sitting on the ground beneath a tall tree staring into a candle.

“Where have you been?”

“Nowhere Father, I have been sitting here.”

“You have been missing for more than a week, where have you slept?”

She pointed to a pile of leaves.

“You are a princess, somebody must look after you, feed you. You must come back with me now.”

“I cannot Father, I am waiting for my rice to cook.”

She pointed up to the top of the tree where the king could see a cooking pot hanging from the uppermost branch.

“But how can you cook rice in a pot hanging in a tree?”

“With this candle Father.”

“How stupid you are daughter! A candle cannot be used to cook a pot of rice, it would not even warm it from down here.”

“But Father, you said that a candle had kept the man in the lake warm. If that is so, as you say, then the same candle can warm the rice in my pot.”

The king felt the cold inside his heart as he realised what she had done to him. She had shown him how pitiless he was. He saw the kindness of her spirit and how it had shamed him. He blew out the candle and took her by the hand to his horse. When he arrived in the palace he ordered the guards to fetch the Sadhu from the prison. As the Sadhu stood before him the king spoke words he had never used before in his life.

“I am sorry. I have treated you unfairly so, please, I beg your forgiveness and if you grant me that I will grant you anything you wish for. Anything that lies within my power.”

While he had been standing in the water and staring into the face of the princess, without knowing who she was, the Sadhu had seen the empathy in her eyes. It was that compassion that had kept him alive. He had understood then, and again later alone in his prison, how important unquestioning mercy for another human being can be. This understanding had given him a deeper, greater strength of purpose and mind.

The Sadhu forgave the king.

The princess knew that true compassion was not simply a helpless pity for someone, but an awareness of their situation and a determination which demanded action. She had acted and then, choosing her words carefully, had held up a mirror to her father’s actions. Through them she had shown him how he, as a ruler, a leader of men, should behave.

The king would change his ways and become a better man because of this.

As for the wish.

All the Sadhu asked for was a place to sleep, sufficient food and a place of peace in which to continue his meditations.

The king granted him his wish.

Through her love, the princess had saved the life of the Sadhu and changed that of her father. She remained happy for the rest of her life.

The Sadhu lived in the palace until he died.

– Christian Rogers, 22.03.02017

Out of the Shadow of the Tree

My grandmother died just as she was about to turn seventy-five. I was thirteen years old. I had not had much contact with or even seen her for a few years because we were living in Devon which is far away from London. At the age of thirteen a few years is a long time. Growing up so fast it is easy to forget about people who are at least out of sight and I only remembered her as an old woman, older than all the other grans of my friends because she had had my father at forty-nine.

Nan was a large woman in so many ways. Larger than life and full of charisma with a manner that was easy to warm to. She was funny. Not in a comical sense like someone who is always cracking jokes or doing mad things—she was just fun to be around. Her eyes had a benignly mischievous look and she was always smiling in a way that made me smile too.

She was simply funny. Different. Odd. I thought so anyway.

Perhaps other people saw her in a different light but these are my memories.

Those memories are few but they are very vivid.

When I was very small we lived in her and my grandfather’s house, on the floor above theirs in sparse rooms without much furniture. We were not well off and money was tight. It was the mid-sixties, a time when post war austerity had not yet been forgotten and todays rampant materialism was unheard of. Working hard and saving up for things was what everybody did. With both my parents having to work at running a business my Nan looked after me. She would pick me up from primary school and take me home. She would feed me lukewarm baked beans on toast soggy with margarine one day and spaghetti hoops the next. The toast, brown on one side only, came out from under a grill above the gas cooker which was black and greasy. She had grown up in a house with servants and maids and I don’t think that she knew how to cook at all but she could warm things up. The kitchen was not a part of the house that looked loved or lived in.

Out the back there was a messy garden full of weeds and cat piss which, on a hot summers day, gave off a smell I have never forgotten. Whenever I was sent off to play by myself or with my cousins when they came around it was to that garden that I went. It wasn’t big. A typical middle-class terraced house back garden. Against a wall at the back was a lean-to potting shed full of empty plant pots, broken crates and a rusted lawnmower. This is where the cats lived. Whose cats they were I never knew. They came and went in and out of the garden and the house too. I think everybody in the street fed them which is why they were all fat. That explained the little craters of shit in the empty patches between the nettles and whatever else those weeds were. I loved the small white trumpet flowers that grew on creepers that wildly smothered everything else, except the nettles which win any game of ‘who can be the wildest’ in a wild garden. We called them granny-pop-out-of-beds because if you squeezed them at the base of the cup the flower head grew in then they popped out and floated down to your feet.

In the house the front room was very much my grandmother’s domain. Here there was a piano on which she tried to show me how to play from a book where the notes were drawn as wide-eyed ants that danced on the staves. I remember lots of crotchets, semi-quavers and Nan’s smiles all seen through clouds of cigarette smoke. Her painted pointed finger nails clacking on the keys.

In the corner, facing the television, there was a faded wicker chair in which she settled down every evening to watch her favourite programmes. Next to her on a curious tall but very narrow table there was a glass of something, which I didn’t like the smell of, and her cigarettes, which curiously I did, When that awful, mournful theme tune of Coronation Street came on I was shushed and banished to the floor. I would play under the piano, parking my toy cars between the pedals pretending they were a garage. Once, wearing short trousers, I knelt in cat shit and vomited. She waited until Coronation Street was over before she wiped my knee clean and the vomit from the carpet. The cat shit was ignored and went crusty so I never played there again.

Sometimes, when my parents had their late nights out in town they put up a camp bed in my grandparent’s bedroom. It was set it up between their separate beds. When Nan came in to go to bed she would pull the bedcover over my head so I wouldn’t see her undressing. Curious as to why something was being hidden from me I peeped and saw her. She was a woman of considerable layers, mostly woolly, which as they were peeled away revealed plenty of flesh being supported by or contained within swathes of stretchy skin-coloured underwear which must have required as much effort to take off as to put on. So she didn’t take them off. When she finally climbed into her bed and the light went out I was left with visions dancing on my eyelids that I rather not have had. Dear Nan.

I am fortunate now because I do not need to rely on memory to be able to find and understand Thelma Tuson. There are other visions to be had. There are plenty of photographs of course, one or two of which are on eBay. But more than that there are pictures that move. My grandmother had been a bit of a star in her time. She had been in the movies and today she can be seen on YouTube singing with George Robey who was known as “The Prime Minister of Mirth” and was recognised as being one of the greatest musical hall comedians of all time.

The hit song from the film was ‘Anytime Is Kissing Time’.

Her name was Thelma Tuson and she was born in South Africa on the 24th of August 1900. In her late teens she moved to London, having won a bursary, to continue studying singing and to work in Operetta. She was a soprano and could sing in Afrikaans. She made a few records, the old 78rpm shellac discs, two of which I have found reviews of in the Gramophone magazine archives from 1928. They contain both bouquets and brickbats for her singing which is probably why she was known as a comedy singer thereafter.

Not much is known about her career apart from the two better-known films that survive today.

Chu Chin Chow was a much-loved comedy operetta which was made into a film in 1934. It is an Ali Baba story—‘See Ali Baba and His Forty Thieves Plunder for Gold and Women!’ A review describes Thelma as portraying ‘a richly funny Alcolom’, the sister-in-law of Ali Baba himself. She is wonderful and gives a delicately sweet comedic performance. The same smile she provoked in me when I was little she provokes in me still whenever I watch the film. Then I was innocent and she simply charmed me, whereas now I am much older, a little wiser and I watch her acting with eyes educated in the same art as hers. Her talent is undeniable and her timing impeccable. Timing is my strength. It is the one thing I really did not have to work on as I learned to use my talents on stage.

It is supposed that talents skip a generation. That is to say that certain traits or behaviour that are present and developed in someone will also be present in their grandchild rather than the son or the daughter. There is no hard evidence for this so perhaps it is just a myth but I have a strong suspicion that it is true. Because I too have made a living out of performance and predominantly out of being funny. I cannot sing though.

Having estranged myself from my family in my teenage years I knew nothing about my grandmother’s life or career except those few memories from my very early childhood. Nothing that could have influenced of informed me in my chosen career. I didn’t see the films that she had been in or listen to any of her records. The last film she had had a bit part in had been made in the 1940s. It was all too distant for anything to have rubbed off onto me.

In my forties I returned to my family after a very long absence and became, naturally enough, curious about the past. With the help of scrapbooks and through listening to my parents I began to piece together a picture of Thelma, rather than my Nan, that would complement my memories. My father gave me a copy of Chu Chin Chow on video. It was grainy and old but watchable and I love the Arabian Nights tales. It is a good film and what a thrill it was to see Thelma as a young woman. She plays a slightly dizzy, scantily clad and overweight woman which gave the screenplay writers a lot of scope to put witty double entendre into the script. She sits around a lot, once on a swinging bed being pushed by two serving maids, while eating and being pampered. She must have loved that.

In A Date with a Dream, made in 1948, she has a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it part. But it was her name, which could still draw punters, that went on the posters because everybody else was so unknown. The film is about young up-and-coming artistes trying to get a show together. The main star was Terry Thomas and it was the first film in which Norman Wisdom appeared. Both of whom would become legends. Thelma was billed as a ‘rehearsing soprano’ and that is exactly what and all she does. Strangely in one scene she appears directly after a juggler. When I saw that the hairs on my arms stood up. It was juggling that gave me my career.

So did I get my talent from my Grandmother? Certainly when I see her perform I know what it is that is making her tick. I can clearly see what she was doing with her character and studying her performance, focusing in on each nuance, I can relate her. So, perhaps I did inherit her comedy genes.

But there is more to Thelma’s story.

She had had a son, she must have been very young at the time, who became an actor and would have gone to Hollywood had he not have died of tuberculosis shortly after refusing to sign a seven-film contract with MGM. He had known that he was about to die while he was making the film. His name was John Hoy and he had starred in the Cannes festival grand prize winning film The Last Chance directed by Leopold Lindtberg. In America the film received a Golden Globe for Best Film Promoting International Understanding.

The premiere in London was attended by both the King and the Queen and John was the star attraction.

How would our family have turned out had he not have died? It is a ‘what if…’ that haunts our family even now.

This of course debunks the generation-skipping talent gene myth.

So perhaps it just more of a case that an apple never falls far from tree. Some roll onto fertile ground out of the reach of the parent tree while others remain in the shadows.

A seed will grow where no shadow falls.

One thing is for sure, both of my grandparents were larger-than-life characters and while not eccentric they were certainly a little bit mischievous. My grandfather also had a wonderful sense of humour. After serving in and surviving two world wars, he became a theatre manager. He wrote poetry and knew a lot about literature. Apparently he was liked by all, especially the ladies.

Thelma married Bob when they were both in their mid-seventies. I was in attendance.

Down the road from their house there was a pub called The Popes Grotto where my grandfather would go for a drink every evening. Dirk Bogarde drank there too. Sometimes the whole family gathered there but I had to sit outside with my orange juice and crisps. In those day children were not allowed in public houses because of the licensing laws so I sat there watching the cars going up and down the Hampton Road listening to the grownups laughing inside. My grandad’s laughter was always the loudest.

What must have I been thinking about? Listening to that laughter all alone outside the pub…

My favourite memory of my Nan, the one which brings me closer to me than all of the others, was sparked by her role as ‘the rehearsing soprano’. After finishing practising her scales she leaves the sound studio and sees some people who had been wanting her to finish. She asks them if she had kept them waiting and when she finds out that they had she pats one of them on the cheek saying, “You silly little boy, you should have told me.”

She would often do exactly the same thing to me.

A pat on the cheek of the silly little boy that I was.

Winnitonka

Telling the stories

I am a storyteller. That is to say that I tell stories to audiences for a living: sometimes to children and other times to adults, at management seminars or business meetings for example. I also work with consulting agencies.

As a storyteller.

Simple.

I don’t read the stories from a book because they are in my head. I have over three hundred of them there already and I am still gathering new ones. New to me that is because the tales that I tell are hundreds, often thousands of years old and in need of a renaissance. They are folk tales, fairy tales and Märchen. “Wonder tales”, as they are called these days, from all around the world.

The differences between reading a story out loud from a book and telling one from memory are many and significant. For a start and obviously enough, it is the possibility to improvise whilst telling which is perhaps the most important. The story lives when it is told freely rather than when read from a page which must be followed. A book becomes a sort of fourth wall forming a barrier which inhibits the magnetic flow between listener and teller. Without having freedom to be expressive, which is vital for interpretation, a reader is bound whereas a storyteller is free.

While telling I am able to observe the audience’s response and, if necessary, can make the narrative clearer without interrupting the flow of the story. I have many possibilities to express the depths and meanings of the tale and to make the experience more enjoyable and meaningful.

Thus the telling of any story becomes a personal experience for both myself and for the listeners. By the very nature of not having a ‘scripted’ text to follow each telling is a unique event. This unique aspect is very important, especially for children who respond positively to such intimate and therefore personal experiences. A listener will have the feeling that the tale was told just for them and only that once. Which in a way it was.

Each telling has a dynamic of its own which depends on a raft of factors. A Monday morning is not a Sunday afternoon. A rainy day is melancholic whereas a sunny one is bright and bouncy. The audience will never be the same twice. The teller never in the same mood. The Greek philosopher Heraclitus wrote that a man can never step into the same river, meaning that everything changes and nothing stands still. This is exactly how we should view the telling of stories.

Telling is a performance which brings its own energies and vitality. When the ‘vibe’ is there then it becomes a self-sustaining act and the teller can move around within the story and explore.

Reading a text or a book does not permit any outcome other than repetition. Therefore the story will not be told in a vivid, living way. It will sound flat and dead.

This might sound harsh. I am often told that reading a book at bedtime to children is worthwhile and beneficial to which I agree. It is certainly better than nothing. But we should try to do better than that. Teachers and parents often say to me that they cannot tell stories spontaneously even stories that they know well. Perhaps they could if they tried. The child would certainly appreciate the effort made to do so.

My partner, in heart and soul, is a teller too. Her name is Kerstin Otto. In fact, she was part of the vanguard of storytellers that piloted a project which brought storytelling into the schools of Berlin predominantly as a way of using stories to support the learning of language. It was found that listening to stories had a big influence to the way children then spoke. I got involved as a foreign language teller and told in a bi-lingual school.

It all snowballed from there as the benefits of having a regular storyteller became obvious.

One day I met with a father of a child in a class where I had been telling, once a week, for over a year. He happened to be an Oscar winning actor and a very interesting man. He told me that he always knew when I had been in the class because on that day, when his daughter returned home, she would not stop talking. Sometimes she would tell him the story that I had told but always she would tell about how her day had been. Her father thanked me for empowering his otherwise shy daughter to speak. He went on to sponsor me with my Telling…Told project and I am extremely grateful for that.

His words empowered me.

THE SELLER OF WORDS

Soul Cages

In the middle of the Neues Kranzler Eck in Berlin, two minutes walk from Zoologischer Garten, there are two large bird cages. In the cages there are birds. Tropical, colourful, and caged.

One morning I arrived in Berlin on an earlier train than usual and way too early for work. To kill time I decided to walk to school. It was a warm morning with the promise of a lovely day. The walk took me past those birdcages.

At that time of the morning, it was just after seven, my mind is at its most sponge-like. Early is good for my brain as it is not yet cluttered. It is open to stuff and I am able to see things clearly. Sometimes it feels like I have taken or smoked something which has given me an exaggerated sense of awareness. But those days are behind me.

So I stood before them. The bird cages. Set in a square of high-ish buildings the two prism shaped cages pointed mockingly, the way out, up to a sky that the birds within would never know.

An immediate hot rush of anger flowed over me as I watched them gliding around within the restraints of the cage. They would pull up, as if slamming on breaks, in sudden surprise at reaching the mesh, the limits of their freedom. It angered me so much. One bird did this time and time again as if some instinct within it couldn’t accept the presence of the restriction, even though it was forced to repeatedly recognise it.

When I was younger I had travelled through Spain and for a while, sick of, and from, picking chemically dusted mandarins, I found work with a circus. My job was to clean out and prepare the elephants. Tarting them up for the evening show. At first I loved it. I was being adventurous, romantic. Like the authors I carried around in my rucksack, Laurie Lee, Hemingway or Kerouac. I was thin, windswept and smelt of elephants. But the attraction soon faded. Seeing, even hearing, them being persuaded to enter the ring by handlers with electric pokers wasn’t pleasant. The young and very naïve idealist that I was wanted to whisper in their ears and say “Please”. After they had performed they were hobbled and put out in enclosures to feed. But at night they were, still hobbled, chained to palettes, large enough for them to lie down on. Often they would stand up all night long and I remember, so clearly, seeing some of them sway from side to side lifting their feet as far as the chains would allow. I would sit on the straw bales and watch them, fascinated, until I realised what they were doing. They were marking time. They were doing what they would have done had they have been free, they were walking, roaming, but they did it in those chains which let them get nowhere. Their eyes were always dull. No wonder.

In Valencia, on Christmas day I left the circus and the elephants, emptied of certain romantic ideas and full of dislike for chains.

That morning in Berlin, watching the birds trapped, but permitted to behave naturally enough for us to delight in them being birds, caught in a small pocket of freedom surrounded by glass, concrete and metaI I felt a complete and utter hatred. Of myself. I was watching them and I could, would, walk away without doing anything to end this unjust cruelty I was seeing. Instead of pulling out a knife to break the net. Twenty years earlier and I would have done just that. I always carried an Opinel in those days.

On the way up the Ku’damm I tried to reason with myself. Now that I was older and wiser, I understood that by freeing the birds I would be killing them. They wouldn’t survive in the wild, especially not in a city. Moreover, trashing the cages would be vandalism. Blah, blah, blah. On and on my thoughts went gradually freeing me from the responsibility of having to honour my own values. I was copping out with the argument of reason.

I was as much caught up in the system as the birds. I was trapped too. And I had to go to work.

The Kurfürstendamm is one of the busiest streets in Berlin. But not at seven in the morning. The shops don’t open in Germany until ten. It was almost empty of people. No shoppers, tourists or building workers. Few cars and even fewer buses.

As I walked along I looked around, back in my sponge mode. Shops without shoppers, doors closed, are just buildings. Lots of glass. Dark inside and lifeless. Turned-off televisions whose screen reflect the room that they are in. Passing a sportswear shop I saw, on the other side of the glass, a cleaning woman working with a vacuum cleaner. Who calls them that these days? She was middle-aged, small and obviously not German. Polish perhaps. She had a worn down look about her as if she had not been properly cared for as a child. The doors were locked and she was inside. The glass separating us. I watched her for a while and thought to myself “Here’s another bird”. She wasn’t happy there in that shop full of bright, shiny things. That was obvious from her expressions. She wasn’t in her natural habitat either. She never looked up, out through the glass doors to the outside world. I couldn’t help comparing her to the birds. “Smash the glass, let her out” I thought. Yeah, yeah. More misplaced idealism.

Walking on, enjoying the sunshine and the thought of going to work, I recognised that instead of having to fight in order to destroy cages we should fight against the building of them. We should not trap anything in the first place. But that is easier said than done, of course. And what about the woman cleaning the floor of the shop? How would she cope without her cleaning stuff? It was all she had.

I was on my way to school. To do some storytelling.

School…Storytelling…

A long time ago my sponge mind had soaked something up by Rumi… Nothing much but…

As I walked along the empty street I let the story weave itself in my mind…

There was once a very rich merchant who came from the south but lived in the north of the country. He was good at being a merchant and had grown very successful. With his profits he had built a large fine house. The merchant was proud of his wealth and wished to display it.

In the hall there were two striking staircases, built to form the shape of flower petals, winding up to the upper floors. He had a library built, the shelves of which he filled with expensive and rare books. The important books he displayed at lower levels so that guests would see the titles and be impressed by his knowledge. In all of the rooms there were fine tapestries and rugs. The dining room was decorated with bright colours, not gaudy but lively. A large mahogany table dominated the room. There was an abundance of silver candelabra. Paintings and long heavy curtains covered the walls. The many bedrooms were no less splendid and guests always marvelled at their airy nature.

To keep the house in order he had a butler, a cook, and some servants. He regularly invited people to dine with him in order to show off his wealth and his taste.

On warm evenings, when he was alone, he would sit in the fine garden, which had been created by the best designer in the land, and would enjoy the perfumes of the flowers on the fresh air while he drank expensive wines. It was all very magnificent.

But the garden was not complete. He felt that something was missing. He wondered long and hard about what that might be and one day decided that he needed a song bird. To remind him of the sound he had heard as child when he had lived, in the south, near to a huge forest full of birds. Yes, that was it. He needed a song bird.

He sent for a trapper and paid him to travel to the forest where he had lived to catch such a bird.

When the trapper returned with a beautiful song bird in a gilded cage the merchant was very happy. He hung the cage in a small pavilion in the garden and would sit and listen to the song which did indeed remind him of his youth.

His guests, amazed by the staircase, the dining room and the garden, and impressed by the books in the library were charmed by the bird in the golden cage. The merchant revelled in this. From then on he needed no excuses to invite guests and they in turn needed none to accept his invitation.

One day the merchant decided to travel back to his birth home in order to do some business. In a generous mood he went the butler, the cook, and the servant and asked them if there was some gift that he could bring them from his journey. The butler asked for a special jacket, found only in the south, that would make him stand out more and therefore better reflect the merchant’s taste. The merchant wrote this down in a little notebook and went to see his cook. Who asked for spices that could not be found in in the north and which would make the food he put on the mahogany table unique, once again reflecting the merchant’s taste. This too was written down in the little book. Next he asked his tailor who said that he wanted a special cloth of a colour only found in the south so he could fashion a cloak for the merchant. He wrote this down, smiling. The servants also asked for things that would improve their work and thus the merchant’s pleasure. He was happy about this.

The evening before he was to travel the merchant sat alone in his garden and meditated. When he was finished he heard a voice behind him.

“And what about me?”

The merchant looked around but could see no one.

“Yes, me. What about me?”

He saw that it was the bird that had spoken.

“What about you?”

“Well, you have asked everybody what they want but you have not asked me.”

The merchant went up to the bird and asked him what it was that he wanted.

“I want you to open the cage for me. Let me out. Set me free. You will not be here to enjoy my song so let me out.”

“But I will be return and then I will wish to hear your song. Besides, you are the most wonderful thing in the garden. My guests would be so disappointed if you are no longer here. I’m sorry but I cannot let you out.”

“I thought you would say that. So, please, I want you to go into the forest near your home, for you and I come from the same place. I want you to go a hill in the middle of the forest where the trees are taller than all the rest, whose leaves are of a green incomparable with other leaves on any other tree. There I want you to shout out to the birds about me. Tell them that I am locked in a cage and cannot return to them. For they are my brothers and sisters, my uncles and aunts. My family. Tell them so they will know and no longer be worried for me. Tell them that I live and, but for this cage, I would fly with them again in that forest.”

“This I will do.” Said the merchant.

He left the next day riding his favourite horse. He was accompanied only by a few servants.

A week later, after a pleasant and peaceful journey, he arrived in the land of his birth. He went to his family home and got straight down to business.

After he had spent some time with his family he went into the city and took out the little notebook with the list of presents. One by one, as he bought them, he ticked the items off and soon he had all that was required. He prepared to travel back north, to his beloved home.

The journey up was as uneventful as the journey down had been. As he rode along the edge of the great forest he was glad to hear the bird song that reminded him of his youth. It also reminded him of the bird’s request. He ordered his servants to wait for him and walked into the forest. It didn’t take him long to find the place. The hill with the greener-than-green leaved trees.

He climbed to the top of the hill and began to shout. At first he felt this to be a stupid thing to do but it was what the bird wanted and so he shouted louder. The forest fell silent. As if every living creature there was listening to him. He was quite enjoying himself now. He told the forest everything that the bird had asked him to tell and then he stopped and listened to the silence. He heard a rustling sound above him and looked up. On the tallest branch of the tallest tree he saw a bird. As beautiful as the one in the cage in his garden.

It was wobbling. Then it leaned out from the branch at a strange angle and, twisting in the air as it fell, thumped onto the forest floor below.

The merchant was shocked. He sat down and he realised that his words must have killed the bird.

“Surely, it was one of my bird’s brothers or and sisters. Perhaps even his mother. The news I gave them has broken its heart.”

Pale and saddened the merchant left the forest and returned on the journey back up north.

A week later he arrived, cheered up now that he was home again. The butler looked splendid in the new jacket. The cook was delighted to be able prepare even more astonishing meals and the tailor got straight down to work on the new cloak. Oh how happy he was!

But he avoided the garden. He was afraid of telling the bird what had happened in the forest.

Some days later he had guests and after the dining and the drinking were over they all went to sit in the garden. It was lovely warm evening and the bird was singing. The wine was smooth and the conversation light. It got late and his guests left. The merchant found himself alone in the garden.

“Well?”

At first he tried to ignore the bird.

“Did you do as I asked?”

He went to the cage but couldn’t look at the bird instead he stared down at the ground as he spoke. He was sad and a little ashamed, but he told the bird, in every detail, exactly what had happened.

When he had said all that there was to say he looked up and saw the bird.

It was wobbling. It leaned out from its perch at a strange angle and fell onto the cage floor. The bird lay lifeless on its back.

The merchant was so shocked that he didn’t react at first. He just stood there staring at the beautiful bird feeling a deep shame. Then he tore open the cage door and reached in. Carefully he picked the birds body up and held it to his heart.

“I must have killed it with the news, just as I had killed the bird in the forest. It is my fault. I have broken their hearts.”

Tears began to fall from the merchant’s eyes as he held the bird in the palms of his hands. Then he felt something and he saw the bird stand up, spread its wings and fly away. His tears of joy turned to laughter as he realised what had happened.

He never put anything in a cage again.

* * * *

When I got to school the story was ready and so I told it. I have done many times since. After one class a student said to me that he found school classrooms to be cages and that he felt that he was trapped within their walls.

“Well” I said to him, “that depends doesn’t it…”

This is one of the reasons why I became so interested in storytelling. Through telling such tales I have the chance to show people that there are ways with which we can empower ourselves and find ways of escaping the traps that seek to keep us in our places. Of course, it is better to avoid those traps in the first place and education is a great tool for this but sometimes we find ourselves caught in traps that are not of our making and then we must rely on help from others.

The question most asked about this story is if the bird in the forest died or not. I never give an answer because I do not have one.

Christian Rogers

March 2017

Christian Rogers is storyteller and performer. A Welshman born and schooled in England, shaped and formed in Wales, France, Spain, Portugal, Italy and Holland and currently living just outside Berlin on a small holding. Phew! He has been performing for just over 30 years most of which have been on the streets of Europe. He has lived in Germany since 1998. He formed the Fleapit Theatre Company in 2001 with Kerstin Otto the renowned and prize winning storyteller and together they perform traditional Märchen with an anarchic twist with the aim of bringing folk tales back to the folk. Until recently and for many years they were the artistic directors of the Weberfest in Babelsberg. As well as having been engaged in many schools in Berlin, working in German, he has been the resident storyteller in the Nelson Mandela School since 2010 and the International School Berlin since 2011. He runs storytelling and performance workshops for both children and adults and works with a number of consulting agencies as both a storyteller and running workshops. He has also worked with the Landesinstitut für Schule und Medien Berlin-Brandenburg. He is the official storyteller for the Vapiano restaurant company.