THE TUESDAY STORY WRITER

★ ★ ★ ★

By Alan Harris

Bruce was a 87-year-old man-of-the-world with pancreatic cancer. He was also a talker and quite the charmer—I could see why the social worker identified him as a good candidate for me to write his story. But despite Bruce’s willingness to talk non-stop for hours, it was difficult at first to uncover his story. If Bruce had his way we would write about his work-life and not about his marriages (four in total). I heard him say as though disappointed in himself that he was unlucky in love. But I watched as his bride of 32 years encourage him to drink his water as the hospice nurse advised. I heard his favorite music in the background—Waylon Jennings crooning about a good-hearted woman in love with a good-timing man. I knew right then and there that I was helping Bruce write his love story. Though he never came out and said it, we both knew who his audience was as his wife changed the record player to an old Roger Whitaker tune.

I have no fear of death

it has no sorrow

and I have loved you dearly

more dearly than the spoken word can tell

I volunteer for Sparrow Hospice, a division of Lansing, Michigan’s Sparrow Health Systems. Our program the Tuesday Story Writers is based on Mitch Albom’s famous book Tuesdays with Morrie, in which he sat with his dying sociology professor for 14 days and wrote his story. I am one of multiple volunteers whose charge it is to meet with hospice patients and listen—and ultimately write their memoir, their story, letters to a loved one, or a poem for whomever comes along willing to read it.

Like Albom I write in the first person, but always from my patient’s perspective. After all, these are not my stories. I am the ghostwriter. But I am also not a tape-recorder that simply plays back what is said. I look for themes. I weave memories along the thread of a story arc. And when the story is finished the patients and their audience—their loved ones, can find meaning in their own life at a time when such an understanding makes all the difference in the world. When that happens the Tuesday Writer’s purpose is also clear. It is the best evidence I have come across that answers the question as to why I am here.

When I listen to the patient I am paying particular attention to life events, particularly those that resulted in an abrupt change. The most interesting of changes are those which produced long-lasting effects on themselves and others. Such changes may seem subtle at first like a decision to alter one’s major in college or a childhood move off the family farm. Some life event changes lead to transitions in roles. The daughter becomes the wife, the mother, the grandmother. Some life events set a person on a new trajectory such as getting their draft notice in 1968. Other times the new trajectory is kicked off by a death: of a parent; of a child; of your best friend in 7th grade.

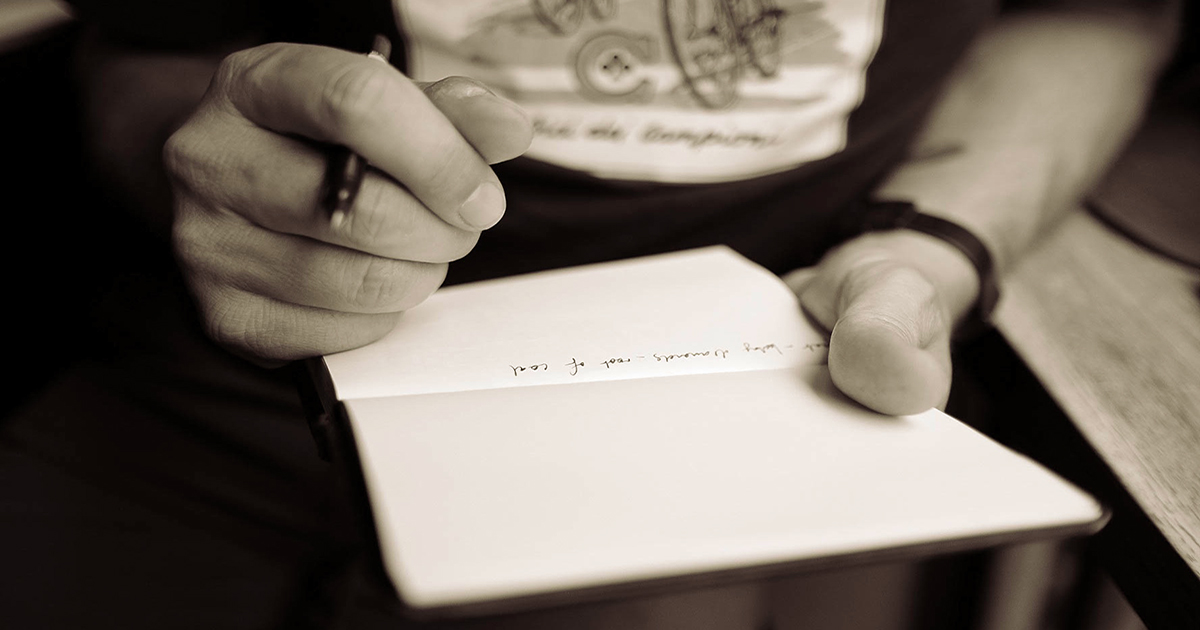

These life events set the stage for journeys to other places, alternate futures, paths they never planned to go down. These memories fill the volunteer writer with a treasure trove of facts and details, sights and sounds from which we carefully construct the framework of a personal narrative not our own. Their story comes alive with our pen, pencil, and touchpad. We ask open-ended questions, masterful questions, Pulitzer Prize-winning questions like…and then what happened?

We are not healthcare professionals. We are writers. But there is a therapeutic value to what we do. By encouraging patients to talk about their life-story, the re-telling has been shown to have a positive, therapeutic effect. The mental health professionals call it ‘Reminiscence Therapy’. Even the mere recalling of memories is often enjoyable for the storyteller. It reminds the patient that they are a real person with an interesting past. And because I listen, smile and share with them a genuine look of awe—they know that their life-story has meaning. For me, it doesn’t get much better than that.

As the end comes near I get busy putting the story together. Sometimes I have 5 pages of notes. Sometimes I have 50. Each story is only limited by how much time the hospice patient has to tell it. My first patient had only 60 minutes of lucid life-storytelling before I had to complete the narrative. That is another reason why that first visit is the most important and why the ability to listen is the volunteer’s greatest skill.

It is not always a story. Some patients simply want help leaving behind letters for their loved ones. But what I will not do is write an obituary. I will always avoid writing, “…he was born here, they married then, he worked over there, and finally died of cancer.” Instead I prefer to start my patients’ narratives in the middle of the action:

I wasn’t ready for it. She caught me by surprise, that big brown mother bear who waited for me at the edge of the meadow—much like the prostate cancer diagnosis a year later.

The first moment I stepped off the transport chopper in Vietnam I could smell what we had done to this place. The foul odor was everywhere not just in Base Camp Blackhorse. When three gallons of diesel fuel is poured in every latrine every morning it leaves a sanitizing stench that the jungle rains can and will never…ever wash away.

So allow me to make a request. Pass a message along to the writers’ groups in your area, to anyone you know who writes. Ask them if they are interested in a new trajectory, a fascinating bend in the road of their own life-story. Then join them as you all contact your local hospice to offer your time, your patience and your skills.

Tell the hospice that you are all good listeners.

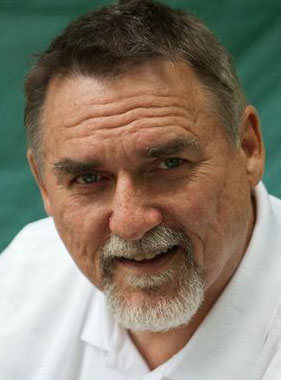

Alan Harris is a 61 year-old hospice volunteer and graduate student who helps hospice patients write memoirs, letters, and poetry. Harris is the 2011 recipient of the Stephen H. Tudor Scholarship in Creative Writing, the 2014 John Clare Poetry Prize, and the 2015 Tompkins Poetry Award from Wayne State University. In addition he is the father of seven, grandfather of eight, as well as a two-time Pushcart Prize nominee.

What a wonderful undertaking! I’m doing this informally with two 90-year-olds in my own family. An organized outreach to hospices would make a huge difference in many lives; I hope many writers heed your call to action.

Thank you, Maria. It is my hope that other writers do as well. Health care organizations are welcoming but there is always the vetting process as they follow protocol for background checks and such. But it is well worth it!

Wow! Alan, this is inspiring. God bless you for the light you shine with your beautiful gift!

Thank you, Kathryn!

Congratulations! What a beautiful thing that you are doing . I’m so proud of you❤️

Love, Becky

Thank you, Becky!

Great job, Alan, for the humanity of it and for the writing. I’m looking forward to your book!

Thank you, Bob.