SPOTLIGHT

★ ★ ★ ★

Transatlantic Thoughts on 9/11

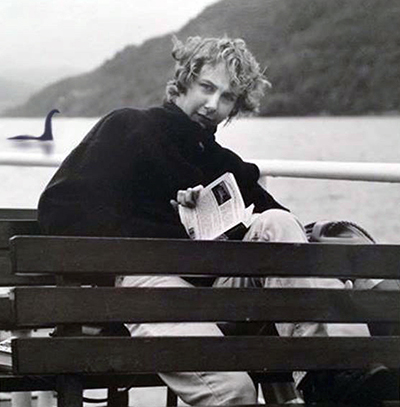

Image by Bjorn Simon

By Maria Behan

I was driving along the west coast of Ireland with my father, who was visiting from California. The weather had been iffy for much of our trip, but that was a sunny, warm day. Maybe it was the other side of the high front that made the New York weather so perversely crystalline that awful morning.

My dad and I stopped for a picnic around two or so, eating late because we’d been holding out for the perfect spot. We found it in a large flat rock surrounded by artistically sloped fields. The Atlantic roiled and glistened in the distance. We gazed at it as we ate our sandwiches, unaware of the horror that was transpiring on the other side of that beautiful sea.

The radio in our rental car started up as soon as I turned the key in the ignition. Before I could make any sense of what the announcer was saying, I was struck—and frightened—by the barely contained emotion in his voice. Reporting on some kind of tragedy that had happened in New York, he uttered words I’ll never forget: “and the world may never be the same again.”

I was born in New York, and it was my home for my first 30-odd years. I didn’t know what was going on, but I knew it was huge and happening to New York and New Yorkers. I started crying. My tough Marine father, a World War II veteran, stayed calm, gently chiding me for being so upset. We both hoped his reaction was the appropriate one.

We reached Leenane, checked into the first hotel we saw, and went into its dingy lounge to watch the TV. There were a few other people there and like us, they seemed sickened and sometimes uncomfortably thrilled by the real-life disaster movie unfolding on the screen above the snooker table. None were Americans, but in Leenane and elsewhere, we received sympathetic looks and comments whenever anyone heard our accents. With glances, nods, or a murmured word, people conveyed that classic Irish sentiment, “Sorry for your troubles”.

We were in Dublin that Friday, which Ireland declared a national day of mourning—the only other country, aside from Israel, to join the U.S. in that. As far as I could tell, more than half of the businesses in the capital, and probably three-quarters of the restaurants, were closed that day.

My father and I appreciated the international solidarity, but we were hungry. When we finally found a hotel restaurant that was open, the staff was apologetic, embarrassed that two Yanks had discovered them working. We were just grateful to be fed.

My dad flew back to the States once the air traffic ban was lifted a few days later, and I flew from Dublin to New York three months after that, for Christmas. As I waited for my bag at JFK Airport, a woman with a Queens accent told me she’d been volunteering at Ground Zero and had seen things she never wanted to see again, things she’d never get out of her head. I didn’t ask her what they were; I didn’t want to know. But I hugged her. New Yorkers are considered hardboiled for good reason, but there we were: strangers who’d never met before and would never encounter each other again, weeping with our arms around each another.

Check It Out

It wasn’t until a year later, during another visit back from Ireland, that I felt ready to visit Ground Zero. By that time, the debris and human remains had been mostly cleared away, and the stench of smoke was gone. A friend and I made our way to a wooden fence with lots of flyers on it: photos, tributes, pleas for information—still, even though it was more than a year after the attack. But that wasn’t what unleashed the tears that flowed as if I were still piloting that tiny white rental car through the Galway countryside, trying to envision the hell that had descended on my birthplace thousands of miles away.

What got me were the people selling lurid photo booklets documenting the Twin Towers’ destruction. The covers were bright, and all involved dark plumes of smoke, smoke that carried bits of metal, glass, and flesh. Those disaster-porn purveyors were hawking their wares with the same muttered commands to “Check it out” I used to hear from the drug dealers in Washington Square Park when I lived in New York in the 1980s.

But that wasn’t the most sickening thing about Ground Zero in 2002; it was the people posing for photographs. They crowded each other out as they vied for space in front of the spots where you could peer into the gaping hole that had been the towers’ foundation. Some tried to look serious as they posed, but most of them smiled, which was worse.

Following a route dictated by my dark Irish-American nature, we then made our way to the Irish Famine Memorial. It’s just a few blocks from the spot where the World Trade Towers stood, but it feels like a different country: like Ireland. The memorial’s centerpiece is the ruin of an abandoned farmhouse that seemed to have dislodged from the Mayo coast, drifted across the Atlantic, and grafted itself onto Manhattan Island. The thing that overwhelmed me was the smell. The memorial’s tiny plot had been planted with flora indigenous to Mayo. I told my friend, an Italian-American who’d never been to Ireland and likely never would, that he should take a deep breath of the country that had become my home.

The Irish have long known that anything from blight to bombs can suddenly reverse both individual lives and national trajectories. Fortunate America’s collective childhood lasted longer than most other nations, but that lesson was finally learned twenty years ago.

America’s response to the terrorist attack—including the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, widespread Islamophobia, and a spiraling distrust of “the other” that spurred the election of Donald Trump—has caused more harm than Osama bin Laden and the others involved in the 9/11 attacks could have dreamed.

That Irish radio announcer was right on September 11, 2001: The world hasn’t been the same since.

Maria Behan writes fiction and non-fiction. Her work has appeared in publications such as The Stinging Fly, Huffington Post, The Irish Times, DailyKos and Northern California Best Places.

Beautiful, Maria. Thank you.

BTW that last comment was from Jon-Marc, who can’t figure out this mysterious interface!

So beautifully written, thanks Maria!