Eric Odynocki

★ ★ ★ ★

POETRY

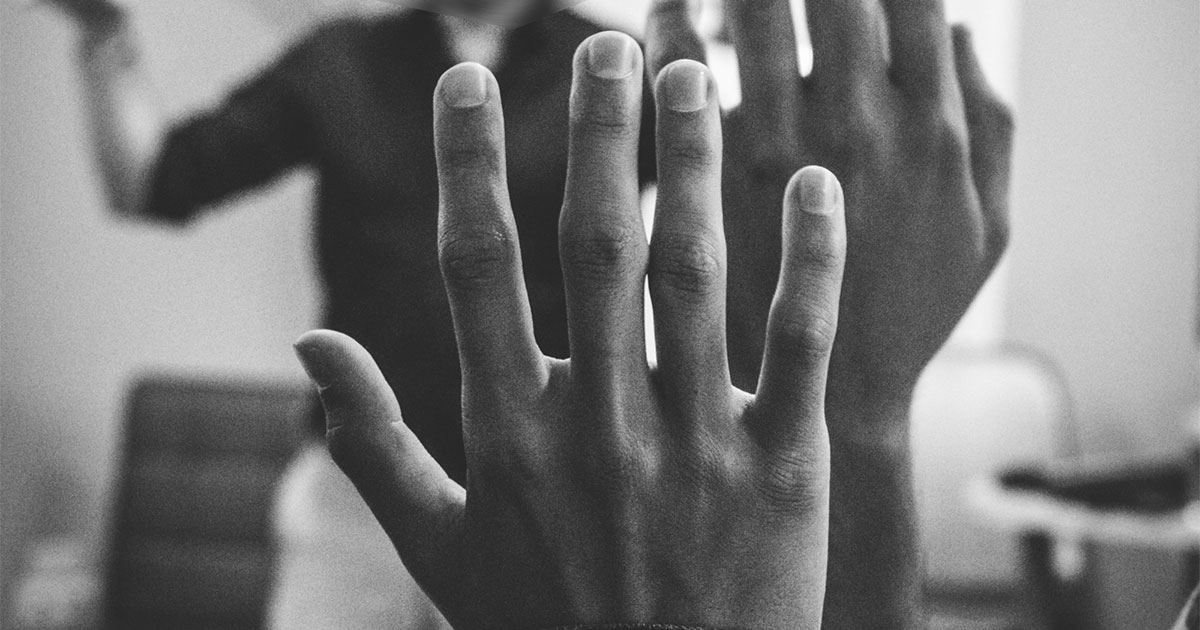

Image by Artem Maltsev

AT A LOSS

From bell to bell I chime to the question

Profe, ¿cómo se dice…? and I pluck

the gleaming lexeme that balances

the scales of translation. I never

have the heart to tell them there is no

perfect translation. Then this winter of

line graphs, when we learn our hands,

even raised, are not immaculate.

And I see the question in their eyes while

I try to mask my own: as the adult,

how do you… what can I… in the time of…

Every morning I sigh with relief after

I check off all the names in the seating chart,

speak non-native normalcy as I thumb through

its dictionary of increasingly redacted entries.

My voice box scars with each, ¿Profe? ¿Profe?

ANAGRAMS

1

Listen, says the speech therapist. She dangles

a card with a house on it. Brown triangle roof.

Red bricks. Green door and single blue window.

Her lips draw back and the black chasm

of her mouth unswallows house. I look at her

mushroom perm. Her oversized sweater of

random, pink and teal shapes. I think she’s

funny. I mimic the sound, yawning like a lion.

I always listen. I just don’t speak. I don’t see

the problem the adults do. On the phone, mom

goes sí, sí, sí. Dad goes, tak, tak, tak. Until they

don’t. And sometimes they cry when they hang up.

2

Mom lay still, listening to the conversations

in the next room even though she had been

tucked in already. A few days later, she listened

from the backseat as her mother and her comadre

confirmed their suspicions, passing by his

nido de amor. Mom hated how much quieter

the house was after her father left.

In those days they treated you like a doll.

3

Silent and listen are anagrams. Escuchar and silencioso

are not. Neither are słuchać and cichy. Linguists see

a common ancestor among the verbs: an Indo-European

notion to incline, to lean in. It survives in sibilants.

Alveolar affricates and velar fricatives. Like the sound

so many cultures make to hush babies, to catch

someone’s attention. Like the sound of the wind

through leaves – the earliest warning. A signal

for change of season or a coming storm.

So many common consonants. All voiceless.

4

I wonder how babcia felt sitting in the one-bedroom

after her last born left. Did she think of those years

in the War? Babcia learned in her late twenties not just

how to listen but what to listen for. That pressing your

lips into a white line could be just as vital as speaking

the tongues of your oppressors. Ja. Да. At the right time.

Afterward, she returned to a quiet that was not solace.

5

You’re not listening if you’re talking. It’s pedagogy 101.

You must be silent like the t in listen, like the letter

that looks like the stick figure profile of a child sitting

with arms outstretched. Before class starts, I exit

the window with all the headlines in either all

blue or all red caps. I open my files, scroll

through my past and future lessons on Lorca’s Casa,

los desaparecidos, las Mariposas. I click

on the presentation about saludos, the importance

of shaking hands and of besitos on the cheek, when

to use tú and usted. In the video conference, I ask

my students a question, remind them to unmute themselves.

LEGENDS

When my students read folklore

of other cultures, I send them

on scavenger hunts for the moraleja,

to match archetypes to their long-lost twins

across storybook borders. Sometimes I pluck

anecdotes from my childhood,

share them like churros or ptasie mleczko.

Like the time I stood beneath Chapultepec Castle

with its halo of afternoon sun. My mother said

when the fortress was under siege, six niños héroes,

teen soldiers, stayed to defend it. Rather than surrender,

they plummeted to their death from the craggy perch.

Before he leapt, the last one wrapped himself

in the Mexican flag so it would not fall into invading US hands.

When I was ten, I walked the cobbled streets of Kraków,

looked up like everyone else at the red bricked towers

of St. Mary’s Basilica when the trumpeter played

the Hejnał mariacki. My father said it was to honor

a boy from the 13th century who alerted the city

to oncoming armies, his plaintive tune cut short

by a Mongol arrow through the throat.

I pause my lesson for yet another

active shooter drill. How do I explain to them

their characters’ arc in this story? I must tell them

to stay huddled in the corner, quiet.

At a Loss

Eric Odynocki is a teacher and writer from New York. His work is often inspired by his experience as a first-generation American with Mexican, Ukrainian, and Ashkenazi roots. Eric’s fiction has been nominated for Best Small Fictions and has appeared in Gordon Square Review and pacificREVIEW. Eric’s poetry has recently been published or will appear in Plume, Brooklyn Review, Cold Mountain Review, American Poetry Journal, PANK, Magma Poetry, and elsewhere.

Such beautiful writing.

Me gusta el poem. Te amo.

Me amo este poem

Me gusta los glizzes

I love this!