FROM THE INSIDE

★ ★ ★ ★

LIFE AND DEATH BEHIND BARS

Image by Bernard Hermant

By Ryan M. Moser

The silence on the other end of the speaker phone is surreal. My biggest fear is realized as I breathe deep and tap my foot on the tiled floor of the chapel office. “Dad,” I say. “l know you can hear me. There are some things I want to tell you… “

My father can’t respond, but l want to believe he can. He’s lying unconscious, brain activity dormant, wires and electrodes connected to his temple and cranium, hair combed just right by my grieving step-mom, gown smoothed across his broad chest, a benign countenance. Machines beep slowly. It’s been 48 hours since his heart stopped. 48 hours since the lack of oxygen to his brain caused him to fall into a coma. 48 hours since I’d learned I will never see my spiritual guide, my mentor, and my paternal guardian again.

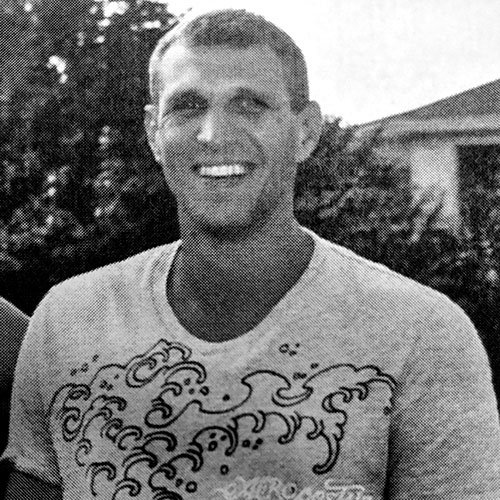

The prison chaplain acts as my emissary, sitting quietly in his office as I speak my final words. My family is 800 miles away in the hospital ICU; my youngest brother holds his cell phone to our father’s ear, allowing me to say goodbye. The pain is only surpassed by the surprise of it all. We’d spoke on the phone two days before; had our regular video visitation one-week prior. My dad was an All-American college athlete who exercised regularly and ate well. A popular university professor in his sixties who kept his luminous mind sharp. Now he is lying cataleptic on a gurney, being memorialized by his loving family as we prepare to let him go. The doctors say he will never regain consciousness again.

I cannot put my father to rest in person (in the respectful way that sons have done for hundreds of generations) because I’m incarcerated in a state correctional institution for burglary. I cannot bury the man who spent his life supporting me unconditionally, even after I broke the law, the man who never judged me because of my addiction, even as it tore my family apart. There will be no placing of flowers upon his grave or bowing as I chant a Buddhist blessing for the departed, no hugs to console his wife of forty years. The punishment of missing my dad’s death and funeral is an exacting toll that I was not prepared for; a price too high to pay; a load too heavy to bear.

When I came to prison I knew that I would lose my freedom, my dignity, my lovers and friends, but never once did I think about losing the right to say goodbye to someone I love; the privilege of sending a parent into the Great Unknown with honor. My folks were too healthy and invincible for me to even consider it. I’d heard other men talk about the agony of losing a loved one while behind bars, but I never put any lasting thought into the matter until today.

Not being permitted to attend a family member’s sacred interment is torment. I was sentenced to ten years in state prison, but there are other penalties that weren’t apparent at the sentencing hearing—failed relationships, not seeing my son’s high school graduation, missed family milestones. Not being able to put my father in his final resting place. These unspoken retributions hurt more than the time I’ve served inside of a cell. On the street my addictions were formidable, but in retrospect, if I’d foreseen the anguish of missing these momentous events, I believe I would’ve changed my life before it was too late. I regret that I didn’t think about the consequences more deeply, but it gives me some comfort knowing that my father forgave me, and because of that I can sleep in peace.

Unexpectedly becoming the patriarch of your family is a sobering realization that life is fragile and should be led with full enthusiasm, something my father did well. I can’t possibly replace him, and being incarcerated takes away a lot of my high ground. After all, I can only be so much of a good role model to my siblings and nieces and nephews from inside a penitentiary. But people can change, and I have. He believed that. Now I can walk out of prison with my head held high, and the memory of my father’s encouragement echoing in my ears. And maybe someday, my large family can look to me for guidance the way we looked to Dad for so many years.

When I shared with one of my friends about my father’s imminent passing, he told several guys in our circle. Most of them are decent men serving time for stupid mistakes. One by one, in my darkest hour, these men came to console me with a pat on the back or a kind word.

“I lost my mom in prison, kid,” one old bank robber told me. “Let me know if you want to talk.”

“Sorry for your loss.”

“My sympathies to your family.”

An army veteran gave me a card and brought me food, knowing that I didn’t want to walk to the chow hall and deal with the daily insanity of prison life. “When my brother died it killed me not going to the funeral. You’ll be okay… in time.”

I was touched and surprised by the humanity around me and realized that many men and women behind bars go through the same tragedies and hardships. The outpouring of support made things just a little easier.

As I write this, my father’s breathing tube is being disconnected from his lifeless body, left to stop functioning by its own volition. My kind and devoted step-mother leans over him, whispering loving words of reassurance and calm. My siblings and aunt cry in the corner of the room, a backdrop to the quietude. An angel sings.

Ryan M. Moser is a recovering addict serving a ten-year sentence in the Florida Department of Corrections for a nonviolent property crime. Previous publications include Evening Street Press, Storyteller, Santa Fe Literary Review, The Progressive, themarshallproject.org, medium.com, thewildword.com, thestartup.com, and more. In 2020, his essay “Injuries Incompatible with Life” received an Honorable Mention award from PEN America, including publication on pen.org. Ryan is a Philadelphia native who enjoys yoga, playing chess, and performing live music. He is a proud father of two beautiful sons.

This column was made possible with the help of Exchange for Change, a non-profit based in Florida that teaches writing in prisons and runs letter exchanges between incarcerated students and writers studying on the outside.

Exchange for Change believes in the value of every voice, and gives their students an opportunity to express themselves without the fear of being stigmatized. Their work is based on the belief that when everyone has the ability to listen and be heard, strong and safe communities are formed, and that with a pen and paper, students can become agents of change across different communities in ways they may otherwise have never encountered.

0 Comments