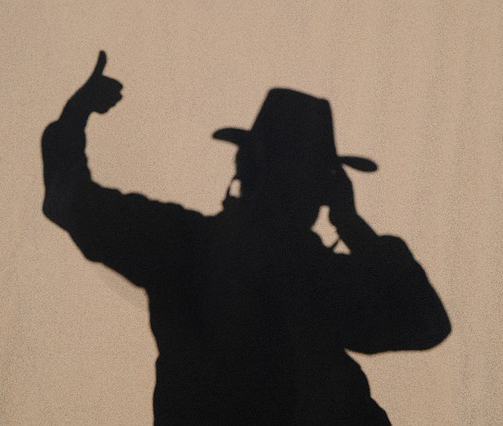

MAN OVERBOARD

★ ★ ★ ★

A new comic serial about a man, his life and the path of most resistance

‘A Small Victory’

By Leif Ecklert

There is something healthy about running a gauntlet every morning. In the front door and through the hostile silence of distrusting associates is very aerobic. All of my subordinates ignored me. Exactly the same as every day since I was promoted to supervisor. I walked into my small, cramped office.

I was living the dream of supervising the Die Cut Department at a fashion leather production facility. Somebody would dream up something fashionable in leather. Our design team would reduce it into manageable parts. The files would come to my assistant “The Coordinator.” She would put the work orders on my desk, and send the large pieces of leather to individual machines to be cut using a hydraulic press, and a die that was really just a cookie cutter that could handle 1500 pounds of pressure.

The cut parts were placed on a cart and sent to the sewing room. Where some other “Coordinator” would have the pieces assembled into an impressive seat cover, or jacket, or vest, or almost anything that was fashionable, made of leather and cost a lot of money.

My real contribution was to sign and log the work orders and report problems. There weren’t many problems, the people who worked for me were efficient, and experienced. They had all been there much longer than I had. Which contributed to the animosity.

On my desk were four manila folders marked “Manpower Requirements, Projections and Allocations,” “Supply Budget Forecast,” “Capital Expenditures, Second Quarter,” and “Process Analysis and Improvement.” They were labeled respectively “Hot,” “Urgent,” “Important,” and “ASAP.” Opening the drawer I put them under a box of emergency crackers my wife gave me. She gives me “emergency” food in case I forget lunch and don’t have time to go out. I ate a handful. We have different definitions of emergency. I turned to my computer and emailed her, “Hey, some cookies would be good next time.”

Ellis stormed in. His red and black checkered flannel shirt was tucked in on the left, but not the right, his shoes didn’t match, and part of his bushy, black hair was standing in defiant solidarity with the disheveled look that meandered down the rest of him. Ellis had a way of looking almost orderly, almost neat, and almost out of focus. His mustache and eyebrows stood out from his face. Somewhere between starting and finishing getting ready he lost track, ran out of time, or just decided he looked good enough. He was the only guy I ever met who could comb half of his hair.

“I need to increase the intensity of my insurgency,” he said.

When they had changed the Art Department to Graphic Design Ellis was mad. “They only did that because it sounds more productive. Not as flaky, more business-like.” He told me. When they hired someone from outside to be the Graphic Design Director Ellis was livid. “They don’t think I can manage an art department?”

To prove he could direct the Graphic Design Department, and to enjoy a bit of revenge, he started a guerilla war against the new art director, the plant manager, and anybody who got in his “damned way, dammit!”

He never asked for my help, but would stop by occasionally and update me on tactics, which were diverse and ingenious, and progress, which was almost non-existent.

Leaving several fresh mackerel in the long abandoned dark room was his first act of rebellion. Noisy flies were constantly buzzing at the dark room door, and the awful stench was starting to spread through the whole building.

The owners sent in a crew of tradesmen to clean the room out. In its place they built an executive lounge complete with espresso and cappuccino machines for senior managers. Which included the Graphic Design Director but not the Die Cut Supervisor.

“I think I got their attention now,” Ellis told me, quietly, confidently, the next day, his index finger pulling skin down under his right eye. A move I had seen before but never understood.

“They are suffering through their frothy, delicious drinks right now.”

“Exactly.” He looked at me, and smiled.

He left loose change on the floor of the Finance Manager’s office, a neat trail of pennies, dimes and nickels, in the shape of an arrow pointing to the safe. On the safe door Ellis had taped a small, neatly lettered sign which asked “Missing something?” The finance guy picked up the change put it in his pocket and threw the note in the trash.

Since the change had come exactly to one dollar he bought a lottery ticket which paid over $300.00. A sum that so delighted the Finance Manager he took all of the senior executives out to lunch.

“How much time do you think he wasted double checking his figures? How many nights did he lie awake wondering if his count is wrong?” He winked at me.

“They don’t keep cash here, at all. The safe doesn’t even lock anymore. All they keep in there is printer paper, paper towels, office supplies and hand sanitizer.” I told him.

“Take a look at this.” He pulled a bottle of hand sanitizer from his pocket, a crooked smile crossed his face, then decided it was not a wholesome place and moved on. He cleaned his hands at me and walked away. I thought he was going to start dancing.

Ellis was, for a time, so sure the revolution was succeeding he tried to grow a wispy mustache and beard like Ho Chi Minh. But, his beard and mustache were so thick, and his grooming habits so erratic the look quickly degenerated into homicidal chic. “Why do people keep leaving the break room every time I go for coffee?” He asked, filling his mug from my coffee pot.

“Maybe they have to get back to work.”

He ended up buying a Che Guevara beret, and man he did look revolutionary in that. Plus he didn’t have to worry about combing part of his hair. It just flowed, curls exploding from the under the brim in wild, almost beautiful disarray. Che would have been proud.

But he had not scored a real “victory” in weeks, and he was getting desperate. It was only a matter of time before the politburo consolidated its power and the masses were sufficiently repressed.

“I made this flyer and hung one in all of the bathrooms.” In the center of the flyer was a roll of burning toilet paper running to jump into the sink, a cigarette dangled from its mouth. No Smoking In The Restrooms in bold demanding letters marched across the top. And on the bottom was the signature, Management.

“They’re beautiful. But smoking isn’t allowed anywhere in the building. It is the state law. Everybody knows you have to stand by the dumpster in the alley if you want to smoke.” They were beautiful. Ellis had a knack for graphic design. His corporate insurgency could use some work, but his art was flawless.

“In two days I am going to take them all down. All of the smokers will think the rules have been relaxed, and start lighting up in the bathrooms. All of the non-smokers will rise up in clean lunged, self-righteous vindictive fury. Management will get crushed between the two forces.” He looked like a victor. A scruffy, sort of unkempt victor who had somehow lost his beret, and forgot to wear socks, and only trimmed half of his mustache, but a liberator nonetheless.

“I guess you thought of everything,” I said, thinking maybe they should put him in charge. It obviously meant a lot to him.

“I did. Oh, I borrowed this,” he said, digging a two-part epoxy syringe from his back pocket and throwing it to me. An expensive glue that we used in the Die Cut Department to hold conductive pads together.

“What did you do with it?”

“I glued the handsets to the bases on all the phones in the art department.”

“But, we’re the only department in the place that uses this glue!” I almost shouted.

“So?” He looked at me, his surprise was obvious.

“They are going to think I glued the phones,” I almost hissed. I was amazed that he was so callous about this.

“Don’t worry, Leif, they’ll think it was one of your malcontents. I don’t know what you’re so upset about, pick one you don’t like, and blame him, or her. You can’t like them all.” He strutted from my office. He was feeling good and it showed.

“Fantastic,” I said, to myself.

The next morning before I could get to the safety of my little office my assistant stopped me and said the plant manager wanted to see me. “It seemed urgent,” she said.

His office was full, every department was represented, and I took a seat at the back.

The plant manager cleared his throat and said, “We have decided to get new phones. They will be delivered today. A fantastic upgrade, we’re all thrilled.”

Please, I thought nobody ask why. Everybody just keep your mouth shut. Nobody ask anything for a change. Just let it die, for once, for God’s sake, just let it go.

“Why?” It was me. I couldn’t help it, I had to know. I cursed myself, but it would have killed me not knowing. Wondering if they were building a case against me, looking over my shoulders, trying to listen in on conversations, I had to know. Were they coming for me?

“Graphic Design needs more capacity, more versatility; they were having a lot of problems with the current system.”

As I was leaving the plant manager pulled me aside. “How well do you know Ellis Flynn?” he asked.

I had to think about that one, but after a few seconds I told him “We’re friends.” It was accurate, and sounded so much better than co-conspirators, or sons of the proletariat.

“Fine, real fine,” He said, putting an arm around my shoulder. “That man has a talent for getting things done. Big things. We are promoting him to Improvement Coordinator, don’t tell him. Big surprise announcement this afternoon.” He shook my hand, punched me on the shoulder and mussed my hair. He smiled, a smile that knew he had won every battle and just ended a war. Then he disappeared into the executive break room for espresso and biscotti. The aroma from the closing door was rich with the caffeinated smell of victory.

Leif Ecklert chased success from Iowa to Ohio. He found glory managing a small department in a small production facility owned by a huge corporation. Married to the woman of his dreams, father of two sons, and firmly entrenched in the middle of the road.