CENTER STAGE

★ ★ ★ ★

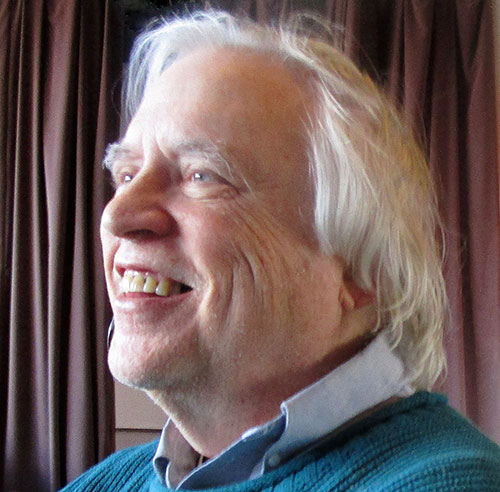

MARTIN WILLITTS JR.

Image by Jamie Pilgrim

Conversation

Many people never talk about death honestly,

as if mentioning the word will bring mortality

and talk indirectly, not looking someone in the eye

when they are dying, as if avoiding will help them.

We don’t have good words for the process.

But death isn’t like that. Not one bit like that.

Each death is different and unique

but ends the same way. Most are more willing to talk

about the beautiful transitions during sleep; less so,

the violent ones. Catch-phrases and euphemisms

like “they look so peaceful, now,”

or “they’ve gone to a better place” are identified.

But I’ve seen the messy side of death during war

as well as a stillbirth. So, I had a heart-to-heart talk

with Death, and Death assures me it’s nothing personal.

Afterwards, I visit the spring-fields,

where trees begin to bud

and Life is busy, quietly planting wildflowers.

Fine-Tuning the Earth

I appreciate when I touch the ground,

it touches back, practically swinging with color.

The odometer of time I’ve spent

highlights my backyard with flowers.

My only solid belief is that earth

Touches and grounds me

to be tender in the garden.

I can squelch the weeds,

but before the day evaporates,

whole clouds scribble

all the words we never say.

The ground assurers me,

I am on time. I plant with color in mind,

the practical music, rooting deep,

reading the message when I open soil,

and the soul of the earth

sings back. It is only common sense

to listen to the fingering of air, the harp

of birds, the intimate release.

I do not believe I deserve this —

generosity — speaking from the ground

through my hands. As if to answer,

a ladybug trundles over my knuckles —

a predator of unwanted insects, a good sign —

opens her red dome shell, shows off wings.

No matter how lost I become in this world,

the universe continues to amaze me.

My Son in the Back Seat Asks the Eternal Question

He persists as soon as we start,

how long before we arrive?

After a mile, the road extends to

are we there yet? We haul forever:

one ghost-shell of a town

after other nameless ones,

offering no rest; just boarded-up

has-beens, never-was places

with graffiti water towers,

fat like mushrooms,

and unkempt fields gone seedy.

He is determined to find an end-it-all rest,

as I transfer from job to failure to unrest,

no sooner unpacking, then uprooting, again.

We never fully arrive, we never fully depart,

pulling up stakes, hammering them in,

yanking them out like pulling unwilling teeth.

He barely makes friends, learns their names,

leans into the secret handshakes, and we’re off

again, jiggety-jig. All he can do is look back

at the unsteady world of what-might-have-been,

as if we’re easily transplanted like tomatoes.

We ain’t there yet.

Q&A with poet Martin Willitts Jr.

Describe your “writer-self” in three words.

Listening to silence

What is the most challenging aspect about writing for you?

Trying to discern what to keep, what to remove, not accepting a first draft as a done draft which is the opposite of Allen Ginsberg’s “first thought, best thought,” but also not as obsessive with revision like the hundreds of versions of Dylan Thomas’ “Do Not Go Gentle into that Good Night.” There must be a balance; it is up to the poet to find it.

Where, when and how are you inspired to write?

I have a daily practice of writing, and the time or where I write is not a factor. I sometimes write poems while waiting at a doctor’s office because I bore easily. For me, it is trying to capture the inspiration whenever it happens. A brain is a muscle and it needs to be exercised. This is why some poets get “writer’s block.” First, just write and don’t think; let the poem tell you what it wants to be. Then, put it aside for a month. Let the poem simmer. Some poets try to recall the poem and basically write it again, and some revise the original.

What are you reading right now?

I am re-reading some poetry on my shelves: Margaret Gibson’s “Not Hearing the Wood Thrush,” and Wally Swist’s “A Bird Who Seems to Know Me.” I think this is the tenth time for both books.

Best piece of writing advice you’ve received?

Re-write everything into first person, even if it happened in the past.

If you could tell your younger writer-self anything, what would it be?

I started writing poetry late in life and I had no one to tell me how to write or submit when I finally got around to writing poetry, therefore, I’d mentor my younger self, help point myself in the right direction and start sooner.

Which poet or character from a book/movie would you invite to dinner and why?

I think it would be interesting to talk to William Blake about his visions of angels, poetry, printing, engraving. I was a handset letterpress printer when I was younger, so I would already know how to print. I have made engravings and woodblocks. He could stay past dinner, sleep in my spare room, and I would be sad to see him leave.

Martin Willitts Jr. has 24 chapbooks including the winner of the Turtle Island Quarterly Editor’s Choice Award, The Wire Fence Holding Back the World (Flowstone Press, 2017), plus 11 full-length collections including The Uncertain Lover (Dos Madres Press, 2018) and Coming Home Celebration (FutureCycle Press, 2019). He is an editor for The Comstock Review.

0 Comments