A KING IN IRELAND’S SONS

Labhraidh Loingseach, 1954

★ ★ ★ ★

GUEST COLUMN

By Pádhraic Ó Dochartaigh

I grew up in a coastal town in the west of Ireland. A day without wind was as rare as a solar eclipse, and when the wind picked up and was joined by icy rain it was best to run for the shelter of your home, if you had one. This story is like that wind. There is no knowing when it will change direction and God knows where it will end up.

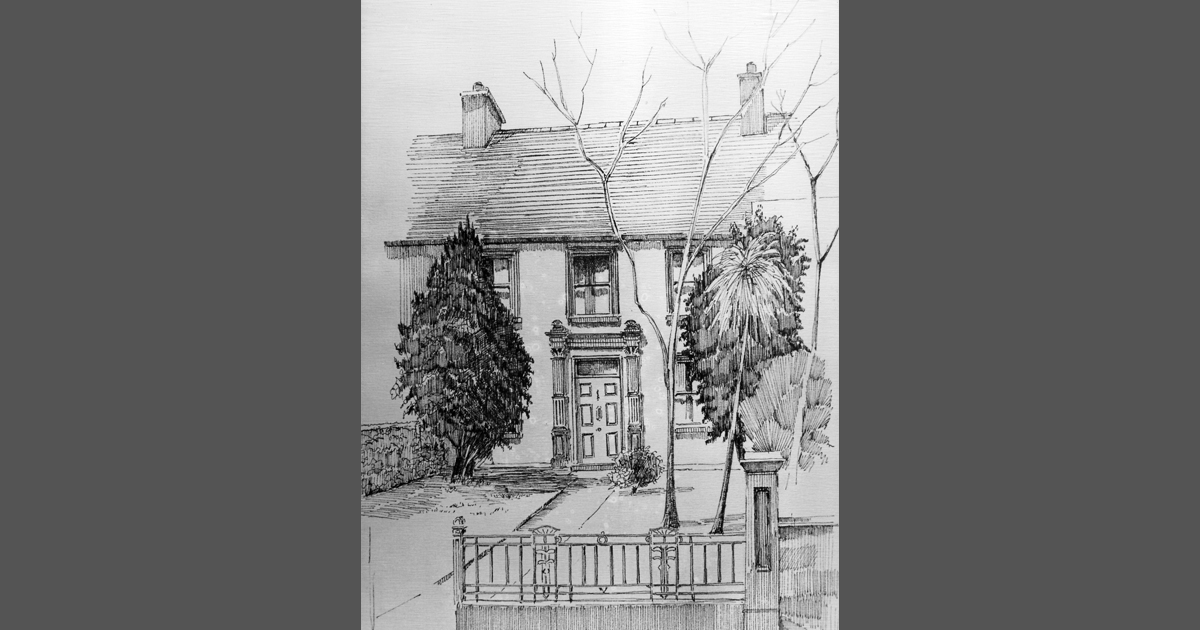

I lived in a magical house in the middle of the town. When you walked in the door it was like passing through the stellar gateway in the Stargate movie. You were in a separate universe. Outside you rarely heard anything but English, inside you rarely heard anything but Irish. Of course we spoke English to schoolmates who came to play because they couldn’t or wouldn’t speak Irish to us. But we didn’t mind much. They were friends and someone to play with. As soon as they left we just switched back to Irish and carried on with our lives.

Going outside was a different matter. We learned early that if we wanted to avoid trouble it was best not to be heard speaking Irish in public. People made us feel it was really rude and deeply offensive to speak Irish in what they considered their domain. And if we were unlucky, we could run into serious bullying—as we did now and then. And so we practiced the Irish art of public silence—of making ourselves invisible.

At some stage our da got a house on the Aran Islands. It turned out to be a second magical house but this time with a magical island all around it. Everyone there spoke Irish to us all day long. No more scowls. No more denigration. We just lived happy children’s lives. Time became an infinite thing with a beginning we couldn’t remember and an end which seemed so far in the distance it didn’t matter. Our only markers were day and night and the small dot which appeared some days on the horizon off Black Head announcing the arrival of the steamer from the outside world.

Da didn’t spend much of the summer with us. He seemed to work all the time. He was a man of the people. Hard work was his weapon. He had schools to build and plenty more to run. They were his castles and he looked after them well.

There was a sense of urgency about all his endeavours as if he had to compensate for the hundreds of years of willful neglect and exploitation the people had been subjected to.

One summer he came for his short annual holidays proudly displaying a pair of fancy hairclippers. From now on we were going to get proper haircuts. So he sat us down one by one on a chair out on the lawn and started practicing. It was a disaster. We wriggled and howled every time the clippers jammed and we got tweaked. And it happened often. The whole affair felt like an execution, with an executioner who hadn’t a clue.

Now there was once a king in Ireland and his name was Labhraidh Loingseach. His name means “the seafarer who speaks”. He was a great king of the Leinstermen and his harper Craiftine played the sweetest music heard on the harp in Ireland in his time.

It is told that the king’s ears had the shape of a horse’s ears and because of this every person who cut his hair was executed immediately afterwards lest the king’s secret become known to anyone.

It was the custom for his long hair to be cut once a year and all the men in the kingdom had to draw lots because of the fate in store for the chosen one.

It happened one year that the lot was drawn by the only son of a poor old widow. The old woman went to the king’s castle and pleaded with him for her son’s life. She had no other relatives and there would be no-one left to look after her if her son were taken. The king relented and promised not to execute her son on condition he swore never to reveal what he would see to anyone for as long as he lived.

The son cut the king’s hair. But soon after he fell seriously ill because of the anguish that keeping the secret caused him. He had to take to his bed and though many tried to help no doctor could find a cure. A wise druid was sent for and after examining the boy he told the mother that the secret was the cause of his sickness and that he would never be cured unless he told his secret.

The druid ordered him to go to the forest and walk up to the first tree he saw on his right-hand side, embrace it, and tell the tree his secret.

The boy went to the forest. The first tree he encountered on his right was a big willow tree. He told his secret to the willow and he began to feel better straight away. By the time he reached his mother’s house again he was completely cured.

Some time after this the king’s harper Craiftine had an urgent problem. His harp was broken. When he was out looking for a suitable piece of wood to fix it, he happened on the same willow tree the widow’s son had told his secret to. He cut a suitable branch off the tree and went back to the castle to fix the harp.

When the wood was shaped and fitted and the harp was restrung Craiftine tried it out. To his surprise the only sound he could get out of the harp was: “Dhá chluas capall ar Labhraidh Loingseach”; in English “two horse’s ears on Labhraidh Loingseach”! The king’s secret was out. No matter how much the harper tried, these were the only sounds he could get out of the harp.

When the king heard about it he was struck by remorse for having killed so many people just to keep his secret. He uncovered his ears and he never tried to hide them again.

Those haircuts spoiled our summer. Lingering anguish festered in our hearts. Would our heads be on the block once a year from now on?

At the end of the summer Da announced he had thrown away the clippers. There would be no more haircuts during the summer holidays. We heaved a sigh of relief and praised our king’s wisdom.

Pádhraic Ó Dochartaigh was born in Galway to an Irish-speaking family. He worked as a writer, TV format developer and producer for BR, Kirch Group and Tele-München. He also worked with SFB and DW-Akademie as a TV programme training development expert. He has lectured and trained extensively at TV stations and media universities in Africa, South-East Asia and China. He lives in Berlin, Germany.

DEAR READER

At The Wild Word we are proud to present some of the best online writing around, as well as being a platform for new and emerging writers and artists.

If you have read the work in The Wild Word and like what we do, please put something in our tip jar.

THANK YOU FOR YOUR SUPPORT!

What a great story. I really enjoyed that. Thanks.