SPOTLIGHT

★ ★ ★ ★

A Dispatch from the Front Lines of the Climate Emergency

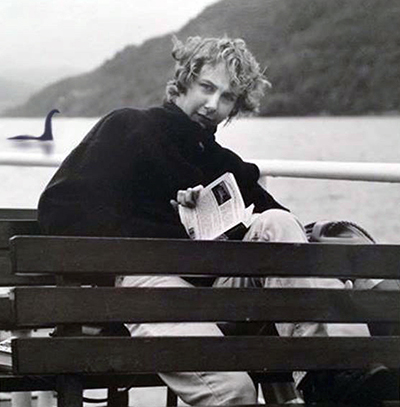

Image by Patrick Perkins

By Maria Behan

Human beings have harmed the environment, and now the environment is harming human beings. Poetic justice, sure. But man, it’s a bitch to live through.

It’s been a couple of decades since we started hearing about how climate change would impact the planet and hence, the creatures living on it. Ice would melt, seas would rise, and extreme weather would get extremer: hotter, colder, windier, wetter, dryer.

Sure, I worried. About polar bears, particularly the mamas and babies we see in Greenpeace calendars. About Venice, an inconceivable metropolis growing ever more inconceivable as the sea around it grows higher. About the Maldives, an island nation I’ve never seen, but hope to visit before it’s reduced to the occasional sandbar jutting out of the ocean…then not even that.

Like any bleeding-heart worthy of that sobriquet, I felt concern for those who’d fall victim to climate change. Islanders losing their islands. Farmers without arable land. But as a first-world denizen only likely to be kicking around the planet for a couple more decades, I assumed the biggest impact on me personally would be higher air-conditioning bills and maybe giving up on that trip to the Maldives.

I didn’t anticipate that privileged people like me would find ourselves on the front lines of climate change. But here we are. And as someone staring down the smoking barrel of what’s looking to be an unprecedentedly hot, dry, and wildfire-ravaged several months, I can attest that it’s unsettling on good days, overwhelming on bad ones.

We used to call climate change global warming, a term that continues to sound apropos in the well-toasted part of the American West where I live. It was 106 degrees Fahrenheit (41 Celsius) when my plane touched down near my home in California following a pandemic-pause vacation centered around drinking in the cool moistness of Portland, Oregon—which stuck close to its average June temperature of 73 F (23 C) when we were there last week. A few days later, that hot-cool temperature contrast flipped, and things got positively freaky. Portland hit 115 F (46 C), shattering not only records for Portland, but for notoriously steamy Houston, Texas. Clearly, something is up besides the mercury.

One casualty from the Pacific Northwest’s late June heat wave is particularly haunting: a man working on irrigation lines who’d immigrated to Oregon from Guatemala a few months before. Dwindling crop yields due to climate change are a big factor driving Guatemalans to migrate north to cooler climes, so it’s heartbreaking to think about that man dying so hot so far from home.

Wine Country Dries Out

Ever experienced drought? I hadn’t until I moved to rural-ish California. And this year, we don’t just have drought, we have “exceptional drought.” The Russian River, the primary water source here in Sonoma County, is drying up. Conservationists are scooping up trout and salmon and trucking them off to locations they hope will retain enough water for them to survive.

They should probably do that for us humans, too. Instead, officials in my town are hoping we can limp along until rain comes again—which likely won’t be until October or November—with a mandatory 40% cut in water use for homes and business. Lawns, that classic symbol of American pride and prosperity, are turning brown wherever you look. And if they’re not, call the city to rat on your wastrel of a neighbor.

Country hikes that were my balm during recent lockdowns now raise my cortisol level. It starts with the dirt under my feet: once muddy or sandy, it’s been baked into something like pottery. Grasses and weeds are crispy and an otherworldly golden-grey that registers on the eye as a vegetal scream. Some vines and trees are already dead, others, fighting to survive, are sickly versions of the colors they turn in autumn. And it’s July.

Whenever I venture near one of the very few water sources left around here, which is mostly swimming pools, I find dead and drowning bees and ladybugs, more than in previous years. Often I rescue the survivors with the brim of my hat, but sometimes I don’t. Why prolong the inevitable?

Then It Ignites

The hot, dry conditions in much of the West are accelerating wildfires at a horrifying rate. For instance, as of 2019, four of the five largest fires in California took place over the past 10 years, which was scary enough. But in 2020, four of the five biggest wildfires in state history happened in that year alone.

I’ve evacuated three out of the past four years, and due to the peril-multiplication provided by the coronavirus pandemic, last August was the most memorable. Yet another fire was burning on the outskirts of my town, the atmosphere so choked with smoke that midday resembled an infernal twilight, so I hightailed it to cooler, fog-bound San Francisco. I have family and friends there, and a few offered to take me in. I declined, fearful that if I pierced their household’s Covid bubble, I might bring the virus along with me.

Instead, I waited out the worst of the fire in a dingy motel that I surmise the city was using as an emergency coronavirus shelter for the unhoused. I heard some worrying things before figuring out that the superannuated air conditioner in my room didn’t generate cool, but it did produce a whole lot of white noise. And I felt way safer among meth heads in that SF motel than in my own bucolic Wine Country community, which once again was getting licked at by wildfire.

I shouldn’t complain, since I’m one of the lucky ones. My sister and brother-in-law lost their home and everything in it during the 2017 Tubbs fire. My nonagenarian aunt had to flee that same fire in the middle of the night after staff at her senior community abandoned the residents, including those with disabilities and dementia, to fend for themselves as flames raced toward them. My father, who’s even older, has been evacuated in the middle of the night twice to escape two other fires. Every time I visit him—still a novelty since they only recently opened his community up to vaccinated visitors—the massive burn scars on the surrounding hills remind me of just how close last year’s Glass fire came. My ex-partner wasn’t so lucky. That same fire devoured the spread we once lived on together, taking his home; the surrounding acres of woods and meadows; and Kylie, a sweet German shepherd who ran off in panic as the flames closed in.

As human beings who presumably can learn lessons from what we observe, my neighbors and I have taken some precautions, made some plans. We clear brush on our properties, pack go bags, map out escape routes. But even locales with more concrete than trees can be burnt off the map, as we saw in 2017, when a wind-driven wildfire jumped a four-lane highway to take out a trailer park and a supermarket. And we can’t know in advance which escape routes might be cut off by approaching fire, how much notice we’ll have, and how many others will be trying to flee when we are.

We don’t like to admit it, but in truth, my neighbors and I are no match for the relentless capriciousness of wildfire. During fire season, we are less like people with agency and options, more like deer: nervous, sniffing the air, always ready to flee. It’s a grim thought, but the truth might be that climate change has made the region I love, a place I’ve lived for the past decade, unsuitable for human habitation.

Some local officials are better than others, but most are only paying lip service to improving the situation while continuing to make things worse. They ask us to let our lawns go brown while they greenlight new developments, including those of obscene scale. The most egregious is an exclusive (and absurdly expensive) resort erected on the periphery of what had been my favorite local hike, though it’s now marred by the beep of bulldozers clearing the way for more of the excrescences that make up the compound. If current homes and businesses are cutting their water consumption by nearly half to try to last thorough the long dry season, how can we provide water for these new complexes? Tourists paying $1,200 a night are going to splash around in their double Jacuzzis, not take truncated showers under low-flow nozzles like us locals.

One of the new developments going up in the ever-expanding outskirts of my town is called Enso, a community for seniors organized by the San Francisco Zen Center. It will likely attract wonderful, spiritual (and well-off) people. But idyllic as the place sounds, where are they going to get the water for all the planned shade trees? And are meditation and chanting calming enough when the air is choked with smoke and a shift in the wind would bring flames your way?

Apparently the word Enso denotes infinity and enlightenment. But when it comes to climate change, enlightenment requires recognition that the resources of the planet are not infinite. And it’s way beyond time we started living that way.

The new developments aren’t just reckless, they’re delusionary. The climate crisis is stripping away our first-world privileges—even new-age Neros hoping to fiddle while California burns are going to have to face up to that. Addressing the climate emergency playing out here in California and all over the world requires bold action. Actions that will disrupt business as usual, depriving many of us of things we’ve taken for granted. Because the biggest thing we’ve taken for granted—Mother Nature—is growing louder and louder as she tells us she will be ignored no longer.

Maria Behan writes fiction and non-fiction. Her work has appeared in publications such as The Stinging Fly, Huffington Post, The Irish Times, DailyKos and Northern California Best Places.

Oh, how I missed your writing Maria.

Unfortunately, all too true. Yet, broad measures to reduce greenhouse gases linger in political battles with naysayers and fossil fuel supporters. I fear not only for the present, but especially for future generations that will experience even worse effects of climate change if we don’t get off of our butts and bring about rapid change to control greenhouse gases.

What an outstanding piece. Kudos to you, Maria!!

“The new developments aren’t just reckless, they’re delusionary. The climate crisis is stripping away our first-world privileges—even new-age Neros hoping to fiddle while California burns are going to have to face up to that.” Amen to calling them delusionary, but I’m not sure the builders and clients WILL have to face up to that. You’ve put your finger on a tiered or class system developing, with only certain folks– the taxpayers– having to foot the bill for negative externalities created by luxury speculation.

You’ve hit on almost every one of my concerns and fears. It is so heartbreaking that those in power in our city continue allowing all this new development for visitors to our city, while Mother Nature and our residents are screaming “There’s a problem here”!

Insightful, daunting, acerbic, quick witted. If only more people were listening…

OOPS…I am anonymous.