NOT ANOTHER TV DAD

★ ★ ★ ★

THE NOTEBOOK

Image by Alicia Christin Gerald

By CL Bledsoe

I first realized my brother was sick when I went to visit him. He lived in Arkansas, where I’m from, and I’m just outside DC. I was sitting in my father’s house when my brother came in. He could barely walk and moved from the door to the kitchen table to a chair, holding himself up on furniture. No one had warned me about his situation. He’d been struggling with a bad fall that exacerbated his back injury but couldn’t afford medical care. It had gotten so bad so rapidly.

His wife and I were able to convince him to go to a doctor, anyway. He was diagnosed with a vitamin deficiency, on top of a back injury he’d sustained a few years prior. But I knew that wasn’t the real problem. The problem was Huntington’s Disease, which runs in our family. Huntington’s attacks the nervous system and the brain, so that you lose not only control of your body but also your memories, your personality.

It was obvious to me, but no one else seemed to agree. I tried to get him to take the test, but he listened to his doctor, who seemed convinced it was something else, regardless of the family history. My brother went into physical therapy in a care facility, found God, and started writing a book.

My brother had several years of recovery where he was able to walk again and take care of himself. He continued his physical therapy and stayed active, but when I spoke with him on the phone, I could hear the difference in his voice. His personality had always been larger than life. Before, he had been a great storyteller. Everything in his life was fodder for a grand epic, even a trip to the grocery store. But after his fall, he didn’t really tell stories anymore. He talked about his bible studies and what he watched on TV.

My brother called me a few years ago to tell me he was writing a book. It was an autobiography about an illness he’d had and (we thought) recovered from. He found God while he was sick, and it gave him peace. He sent me a few pages, and I encouraged him, because that’s what you do.

I had a difficult childhood. My mother was dying from Huntington’s Disease, more of an invalid than a mother. My father was usually out drinking with his friends. He had no time for this weird, bookish boy born late in life. My brother was eighteen years older than me, and people thought he was my father. In many ways, he was. He always had time for me. He took me to concerts and Cardinals baseball games. He would take me on long drives out in the country where we’d listen to music—he would quiz me on the names of the musicians and the songs. He watched movies with me. Everything was a joke, to my brother. Anything a person said or did could be reimagined as a jape. He had a quick wit, and it was a constant contest to try to tell the funnier story or make the better joke. But it wasn’t just a competition; it was about delighting in life. Finding joie de vivre, though I’m sure he wouldn’t have known what that phrase literally means.

A couple of years ago, my brother started falling again. He had a walker, but caring for himself—basic things like going to the bathroom and showering—were difficult. Eventually, he had to return to a care facility. His spirits seemed crushed. He deteriorated rapidly. I went to visit and was shocked by how thin he was. How difficult it was for him to feed himself or even turn over in bed. He wasn’t able to walk anymore. He couldn’t read his bible anymore. I fed him snack cakes and gave him water. We decorated his room for Christmas. I went back home and was told he’d been rushed to the emergency room because he’d thrown himself from his bed in an attempt to kill himself. A couple months later, he was dead.

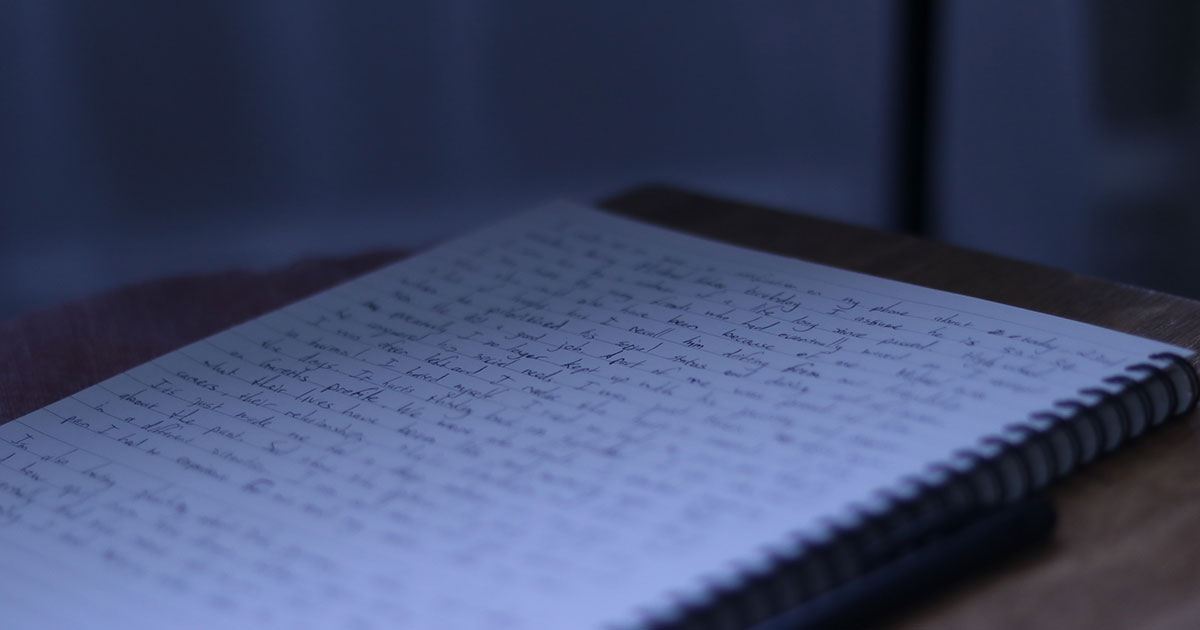

After the funeral, I flew home and my brother’s widow called. She told me he had finished his book about his life. He filled up a notebook before he was no longer able to write. She said she was going to mail it to me, to see if I could use it to write something about him.

Days passed, then weeks with no sign of the notebook. I contacted the post office, who said it had been delivered, though it obviously had not. They said they would investigate it, and I didn’t hear from them again. Then, one evening, I heard a bang on my door. I went and checked and someone had left a package. It was the notebook.

At his funeral, people I barely recognized would tell me stories I’d forgotten about my brother, about the life I’d left behind so many years ago. He had been in misery, those last few months. He was in pain from his nerves dying. He had all sorts of physical problems due to the ravages of Huntington’s. When he could still talk on the phone, I would tell him stories about things we did when we were younger, about how much he’d meant to me.

I haven’t read his book yet. I flipped through it. The writing deteriorates as it progresses. It’s smudged and, at times, difficult to decipher. I will need to sit with it for a long time, and I don’t have the bandwidth for that yet. Grief will have to lessen its grip on me a little. But I’m so glad to have this glimpse into his life, this reminder of his personality. When my mother died, I found a diary she’d started when she was a kid, and then continued later, when she was a teenager. The thing that stood out most about it was how banal it was. This woman who’d been dying most of my life had gone to the movies. Dated boys. Been mad at her parents. Tragedy overwhelmed her life, but this snapshot of who she was before that is so valuable to me.

It’s the same with my brother. This notebook, regardless of when I get to read it, is a beautiful reminder of his humanity. His dignity. Something that happened with my mother and then with my brother is that the immediacy of the illness began to overshadow my memories of them. I forgot who my brother had been. His warmth and humor was replaced by his suffering. The notebook gives me a chance to remember him more fully. I’m grateful for that chance.

CL Bledsoe is the author of sixteen books, most recently the poetry collection Trashcans in Love and the flash fiction collection Ray’s Sea World. His poems, stories, and nonfiction have been published in hundreds of journals and anthologies including New York Quarterly, The Cimarron Review, Contrary, Story South, and The Arkansas Review. He’s been nominated for the Pushcart Prize fifteen times, Best of the Net three times, and has had two stories selected as Notable Stories of the Year by Story South‘s Million Writers Award. Originally from a rice and catfish farm in the Mississippi River Delta area of Arkansas, Bledsoe lives with his daughter in northern Virginia. He blogs at NotAnotherTVDad.blogspot.com

0 Comments