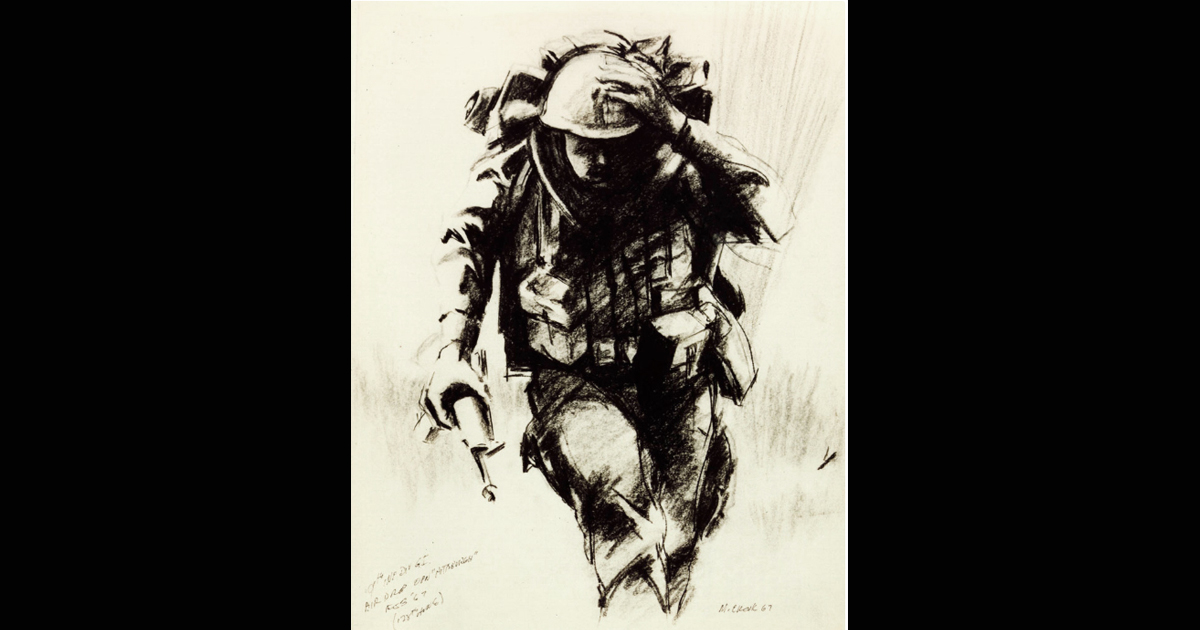

ORIGINS

★ ★ ★ ★

ALAN HARRIS

Full Measure

Lincoln said it at Gettysburg

of how

they gave the last full measure of devotion

Jimmy was from Boston

his dad had died

and his mother had to raise his special needs brother alone

Vietnam never called him

he was the man of the house

he could have stayed home

But Jimmy enlisted and took the higher pay rate

the combat bonus

to send home to his mother

He was stationed in Camp Blackhorse

drew the sympathy of commanding officers

and given a repair rig to drive

But the VC were neither sympathetic

nor knowledgeable

about US Army vehicles

the smaller faster trucks stocked with ammo

were both in front and behind

the boy from Boston

All he was hauling were spare parts

gears, tires, a transmission

along with a commitment to send his paycheck home

Charlie hid in the field

waited until the largest vehicle lumbered by

and detonated their deadly charge

Ammunition got to where it needed to go

tires and gears and transmissions

were easily replaced

But a son’s love

his last full measure of devotion

lay scattered in the jungle far from Gettysburg and Boston

By Alan Harris

My hospice patients do not realize how well they tell a story. Memories flow like a well-spun yarn. These yarns often bind up a hidden wound or a heavy heart. As I write their hospice narrative, part of me believes that my role in converting these honest, genuine and sincere recollections of the past is to break the bind. In so doing, a wound may bleed again but on the other hand, a heart can be released from its tether. I keep my questions simple, mostly open-ended. These stories I am gifted with fall into a variety of thematic categories. A common pool of memories that many old soldiers pull from are slices of life while in uniform. Some veterans hold on to these narratives as though stamped “Classified” and for their eyes only. One particular hospice patient who had survived the Vietnam War shared several stories with me. Most of which revolved around family, around mothers and sons, around brothers-in-arms, although home and loved ones were a world away.

One day I asked my patient whom among the soldiers he had met stood out five decades later. He thought about it and then told me the story of a young man from Boston. He lived with his mother and little brother whose special needs required costly medical care. His father was not there nor was part of this story except to point out that his son was now the man of the family, the male head-of-household. The boy from Boston could avoid the draft, a situation many enlisted men, including my patient, were envious of. The young man was not well-educated. The family had little means. But this eldest son felt a moral obligation to his mother and brother to enlist in a war that did not pursue him and to dutifully send his paycheck home like a good son.

He had learned of the opportunity to earn combat pay and did not hesitate to increase those earnings for his family back home. That’s where they met in Base Camp Blackhorse. The young man’s backstory made the rounds. He quickly became everybody’s little brother. In a jungle far from home, embracing a new grunt as one of your own kin was a common and worthwhile pastime. The very first thing his new brothers did for him was to take the young man out of night patrols by convincing the Commanding Officer that the boy was an experienced truck driver. Everyone knew that night patrol grunts were the first to use up the body bag inventory. Then they put him behind the wheel of a basic parts truck. He carried no weapons, ammunition nor explosives. My hospice patient drove the more dangerous munitions truck, a smaller vehicle that replenished supplies in the field.

He told me in great detail about the morning their convoy headed out to deliver supplies to a camp closer to hostilities. My patient got behind the wheel of the smaller truck filled with ammunition. The young man from Boston drove the bigger, safer truck loaded with spare replaceable parts. How that story ends and why it remains a vivid memory after 50 years challenged my ability to entrust it to verse. My hospice patient had shared this important memory on the anniversary of Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, November 19th. I wrote ‘Full Measure’ before the day was done. I can only hope that the bleeding is over and my hospice patient’s heart is finally untethered from the grip of dark memories.

“Full Measure” is a poem from the forthcoming full-length poetry book entitled “Fall Ball: Poetry for the Late Innings“, published by Finishing Line Press. Available in December.

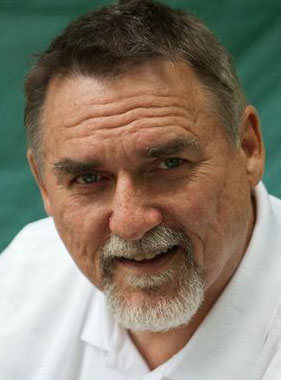

Alan Harris is a 61-year-old hospice volunteer and graduate student who helps hospice patients write memoirs, letters, and poetry. Harris is the 2011 recipient of the Stephen H. Tudor Scholarship in Creative Writing, the 2014 John Clare Poetry Prize, and the 2015 Tompkins Poetry Award from Wayne State University. In addition he is the father of seven, grandfather of eight, as well as a two-time Pushcart Prize nominee. He has a poetry chapbook, Hospice Bed Conversations (Finishing Line Press) and Finishing Line Press will also publish his full-length book of poetry, Fall Ball and other late-inning storylines, in December.

DEAR READER

At The Wild Word we are proud to present some of the best online writing around, as well as being a platform for new and emerging writers and artists.

If you have read the work in The Wild Word and like what we do, please put something in our tip jar.

THANK YOU FOR YOUR SUPPORT!

Man, that is a great poem, and it has to be a tough job. I’m glad that somebody does it.

Thanks, Tim.