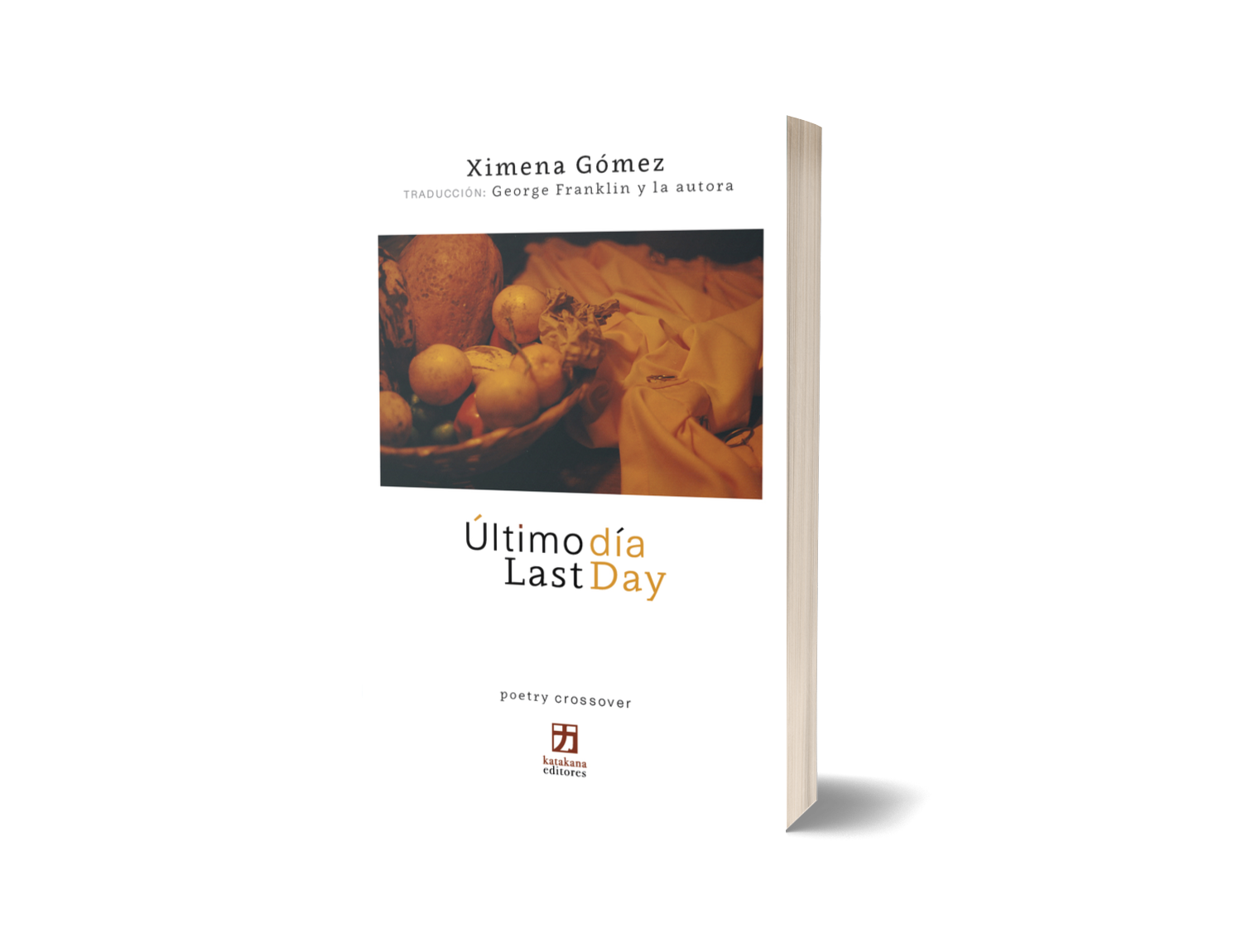

‘Último Día/Last Day’

★ ★ ★ ★

POETRY BOOK REVIEW

By María José Claros

Último Día/Last Day is the newest poetry collection by the powerful poetic voice of Ximena Gómez. Divided into three very different sections, the author presents us with a portrait of her loved ones. In the first two sections, Gómez anchors her narrative in images and memories related to her parents. In the third, the poems revolve around her partner. This poetry collection captures the reader by its intimate and melancholic depiction of the familial as the poet brings us into a very personal universe through her craft. Though this universe may seem provincial, the poet transports us from the local into the universal, from empty rooms into feelings of tenderness.

The spaces her loved ones inhabit are carefully created through a deft use of language and concrete images, and repetition in the shape of free verse. These techniques help order the poet’s memories and also establish a dialogue with her dearly departed, who come back to life through her poetic voice: “Because I feel you alive/In this microcosm of soil.” Using different objects in varying aspects, she tackles universal themes such as death and love. Although these objects may seem cold and distant, they suggest what unites us, showing us the beauty of the common and ordinary.

Last Day is Gómez’s second collection, her first poetry collection, entitled Habitación con Moscas – Room with Flies was published in 2016 by Torremozas. In that collection the author had already started to work on literature as micro-geographies in the shape of poems. Through intimate, and necessary, nostalgic introspection, her memories guide us back to a realm of the local and domestic. Thus, we can find a poem entitled ‘You’ll know how to make it home’, where the author invites us to “See the secret entrance/The door is half-open/Come in.”

This second collection starts with ten poems grouped in a first section called “I dream of her in a room without a door”, where the author invites us into her childhood birthplace. Some poems are illustrated with black and white photographs, which help us imagine the journey into her own past. A hallway, a dining room with an armchair in, and some windows covered by ivy steer us through the intricacies of her narrative memory.

This private universe is opened to us with the first unsettling image of a cockroach sliding down the curtains of her bedroom. This disturbing scene is recreated in the opening poem of this collection called ‘Paramnesia’. Paramnesia describes the phenomenon of not being able to distinguish real from imaginary memories so we become aware that we should be alert to those memories the poet shares with us.

It comes as no surprise that she starts with this creature to which she had already dedicated the opening poem of her previous Room with Flies. Then she stopped to watch the insect in the shape of a leg trapped in the cracks whilst now it slides down the curtains “Drunk with poison.” It reminds us that it is the author, the only owner of her own vision, who is entitled to remember what she wishes from whatever angle. The Asturian poet Antonio Gamoneda, who Ximena Gómez admires, was also aware of how memories can get entangled and become murky when toying with nostalgia: “Someone has entered the white memory, in the stillness of the heart./I can see a light in the fog and the sweetness of the mistake makes me close my eyes.”

Gómez keeps on recalling her mother and recollecting from that “white memory” through the first ten poems, though her father is also present as another type of loss. Like the Imagist poets, she uses the stroke of a few impressionistic brushes of those childhood places. Her mother appears under the roses, in a black and white photograph, where we can hear the flapping of her flip-flops, feeling her presence. This is the feeling I get from the poem entitled ‘Living Room Set’, probably the most humane and humanizing of them all.

As the Northern Irish poet Seamus Heaney did with his renowned sonnet sequence ‘Clearances’, Gómez recreates those spaces occupied by her loved ones, filling them up with flashes of her memories: “Then, as I got used/ To that sunlight,/ That vacancy, That’s where she settled,” the poet confesses. There is also another relevant poem entitled ‘A Revelry of Birds’, where the writer wishes to cauterise her wounds after losing her mother. She imagines herself as a duck, with feathers coated in oil, so she may relieve the pain after the loss. This first section ends with another poem called ‘Zapateado’, where she recalls her mother half asleep in her armchair. In this poem the poet hears the tapping sound of her mother’s shoes so loud that she appears again asking her “What time is it?” Once more, our memories help us live with our ghosts.

The second section is called “There are no more bird sounds”. Here she vindicates nostalgia as an introspective dialogic tool. Her mother is absent, but that silence is broken by the poet, who addresses her ‘In the Next Room’. This is another great poem, which serves to exemplify enumeration as a technique that characterizes the author. Here Gómez unearths from her memory objects like the chair, the desk and the bookshelf that once stayed in that room. Perhaps she revives them from oblivion to heal old wounds such as “a handwritten card” that she never gave to her mother.

In Ancient Rome a poet was called a “vate”, meaning both poet and prophet. We can apply this term to this collection as the poet presents those objects as sortilèges, endowed with magic. She places them for us to dig in her own archaeology and roots. Such is her devotion for inanimate objects that most of her poems appeal to us as still lives. Her vision can sometimes leave us cold, where it is only animals that can seemingly alter her static sense of order through scatological scenes, like the aforementioned fly that “courts the feces of a horse.” in the poem called ‘Eden’.

In these first two sections there are moments when the poet’s very precise focus on the objects make the reader disconnect from those absent characters who inhabit her poetic universe. This feeling ceases in the third section of her collection, “Under the sheets, we spoke in whispers”, where the presence of her partner draws us closer. He appears walking on the streets of Chicago, again portrayed among everyday objects, like some clothing that will lead them into a passionate encounter in ‘Bathrobe’ or some sheets that still smell like him in ‘One Monday’.

Last Day ends with the poem that gives this collection its title. Here Gómez looks prospectively at a last moment together before it all ends and there is no more space for objects to be placed one against the other. It is a closure to the poetic space she has walked along in this powerful collection, one of empty rooms, unhealed wounds, memories and begrudges but also of sweet nostalgia.

* * *

Último día / Last Day es una obra de gran fuerza poética donde Ximena Gómez nos presenta en tres bloques claramente diferenciados un retrato de sus seres queridos. En los dos primeros la autora ancla su voz narrativa en imágenes y recuerdos relacionados con sus padres, mientras que en el tercero el protagonista es su pareja. Esta colección atrapa al lector porque es un retrato intimista de imágenes muy familiares que hay que descifrar desde la melancolía. La autora nos transporta a un universo muy personal al elaborar imágenes que requieren un esfuerzo añadido al lector de poesía. Su tono puede resultar un tanto costumbrista pero la autora consigue sublimar la realidad y pasar de lo local a lo universal, de estancias vacías a sentimientos de ternura.

Sus seres queridos habitan espacios que son descritos mediante un lenguaje directo que se articula mediante la enumeración y la repetición en el marco del verso libre. Estas dos herramientas le sirven a la autora para ordenar sus recuerdos y también para dialogar con los que ya no están, aunque gracias a su voz poética reviven con el pulso de la palabra: “Porque te siento viva / En el microcosmos del suelo”. Con múltiples enumeraciones de objetos, la autora aborda temas universales como son la muerte y el amor; aunque aparentemente nos pueden resultar fríos y ajenos, estos objetos pueblan un espacio y aluden a aquello que nos une. Ahí radica el atractivo de lo común y lo cotidiano.

Último Día es en realidad la segunda incursión de Ximena Gómez en el complejo mundo del género poético ya que Habitación con Moscas supuso su debut como poeta de la mano de Editorial Torremozas en 2016. En esta colección la autora ya dio muestras de cómo la literatura sabe de micro geografías en forma de poemas, donde la memoria rescata desde la nostalgia un mundo doméstico y local que necesita de ese ejercicio íntimo de introspección. Así lo percibimos en el poema ‘Sabrás llegar a mi casa’, al que llegamos invitados de la mano de la autora: “Verás la entrada secreta/La puerta está entornada/Entra.”

Precisamente este segundo poemario arranca con una decena de poemas agrupados en un primer bloque titulado “Con ella sueño en una habitación sin puerta”, donde nos invita a adentrarnos en la casa de la infancia de la autora. Las fotografías en blanco y negro que se incluyen después de algunos poemas nos ayudan a visualizar ese camino de recuerdos. Un pasillo, un salón con su butaca y unas ventanas al jardín tapadas por una hiedra nos sirven de guía para no perdernos por los entresijos de su memoria narrativa.

El primer bosquejo nos presenta una escena que le hizo sentir pavor, el aleteo de una cucaracha que se coló entre las cortinas de su habitación. Esta imagen perturbadora la recrea en el primer poema de esta colección: ‘Paramnesia’. Este término médico se aplica a la alteración de la memoria por la que el sujeto cree recordar situaciones que no han ocurrido o quizá altere otras que sí han acaecido. Podemos interpretar pues que el lector ha de mantenerse alerta ante la veracidad de los recuerdos que Ximena Gómez va a compartir con el lector.

No es casualidad que haya empezado con este animal, le dedica también el primer poema de su anterior Habitación con Moscas. Entonces se detenía a observar al insecto en forma de pata atrapada entre las grietas mientras que ahora cae por las cortinas “ebria de veneno”. Al fin de al cabo, quién sino el autor para ser dueño y señor de recordar aquello que quiera desde la óptica que prefiera. El poeta asturiano Antonio Gamoneda, admirado por la propia Ximena Gómez, también supo que en los juegos de la melancolía hay recuerdos que se pueden entremezclar y volverse turbios: “Alguien ha entrado en la memoria blanca, en la inmovilidad del corazón./Veo una luz debajo de la niebla y la dulzura del error me hace cerrar los ojos.”

Durante los diez primeros poemas, Gómez va a seguir ofreciendo una suma de recuerdos que habitan en esa “memoria blanca” que en gran medida giran en torno a su madre, aunque su padre también aparece como otro tipo de pérdida. Lo hace al modo de los poetas imaginistas ingleses y norteamericanos, con meras pinceladas impresionistas de esos lugares de su niñez. En retrospectiva aparece bajo los rosales, en una foto en sepia; quizá oigamos sus pasos en forma de chanclas o podamos incluso sentir su presencia. Esta sensación es la que me provoca el poema titulado ‘Juego de Sala’, quizá el más humano y humanizante de todos.

Como hizo el poeta norirlandés Seamus Heaney en su afamada secuencia de sonetos ‘Clearances’ (‘Vacíos’), Gómez recrea los espacios que habitaban sus seres queridos e intenta llenarlos con destellos de su propia memoria: “Cuando me acostumbré/A esa luz del sol/A ese vacío/Ella se instaló allí”, confiesa la autora. También destaca otro poema titulado ‘Algarabía de pájaros’, donde la escritora quiere cauterizar las heridas tras la pérdida de su madre imaginando ser una hembra de pato no de pájaro – somos víctimas de nuevo de la paramnesia – pertrechada de plumas bañadas en aceite. Sólo así parece mitigar el dolor de la pérdida. Este primer bloque se cierra con otro poema -cuadro- bosquejo titulado ‘Zapateado’. Primero la autora recuerda a su madre en un duermevela en el sillón, pero revive gracias al sonido de un zapateado con tal fuerza que consigue que dicha presencia o quizá ensoñación le llegue a preguntar “¿Qué hora es?” De nuevo, la memoria nos ayuda a convivir con nuestros propios fantasmas.

El segundo bloque de poemas se titula “No se escucha ningún pájaro”, donde Ximena Gómez sigue reivindicando la nostalgia como herramienta de diálogo introspectivo. Su madre ya no está pero ese silencio es alterado por la voz poética de la autora quien la invoca en ‘En el cuarto de enseguida’, otro gran poema que presenta una técnica que caracteriza a la autora: la enumeración. Ximena Gómez consigue que sus catálogos de objetos – la silla, el escritorio o el anaquel que habitaban esa estancia – dejen de estar soterrados en la memoria y sean rescatados del olvido para quizá curar viejas heridas como “una tarjeta/Escrita a mano” que nunca llegó a entregar a su madre.

En la antigua Roma, al poeta se le denominaba vate porque se le atribuía poderes adivinatorios. Bien podemos aplicar este término a este poemario, donde se disponen todos esos objetos cual sortilegios. De este modo, la autora los coloca para que excavemos en la arqueología de su pasado y sus raíces. Es tal su preferencia por las naturalezas muertas que muchos de sus poemas parecen auténticos bodegones. Su mirada a veces nos puede dejar un poco fríos ya que sólo los animales parecen alterar su orden estático mediante momentos escatológicos, como de nuevo una mosca “cortejando las heces de un caballo” en el poema ‘Edén’.

En estos dos primeros bloques hay momentos en los que al poner de modo tan preciso el foco en lo material, el lector puede perder el contacto humano con los personajes aparentemente ausentes que habitan el universo de la autora. Esta sensación se ve interrumpida en la tercera parte de este poemario, “Entre sábanas hablamos en susurros”, donde sentimos más cercana la presencia de su pareja. También aparece dibujado entre bosquejos de un paseo romántico por las calles de Chicago, de nuevo entre objetos de lo cotidiano como una prenda que conducirá a un encuentro apasionado en ‘Bata de baño’, o unas sábanas que todavía conservan su olor en ‘Un Lunes’.

Último Día cierra con el poema que le da título a esta obra de modo que Gómez lanza una mirada prospectiva a un último momento juntos antes de que todo termine y ya no haya espacio en el que los objetos se ordenen unos contra otros. Es un punto final a un espacio recorrido de habitaciones desiertas, de heridas por cerrar, de recuerdos y reproches pero también de dulce nostalgia.

Ximena Gómez is a Colombian poet, short-story writer, translator, and psychologist. Translations of her poems into English have been published in Sheila-Na-Gig, Cigar City Journal, Two Chairs, The Laurel Review, Nashville Review, Gulfstream, and Cagibi. She has published two collections of poetry, Habitación con moscas (Ediciones Torremozas) and Último día / Last Day (Katakana Editores), whose title poem was a finalist for The Best of the Net award in 2018, and a translation of George Franklin’s Among the Ruins / Entre las ruinas (Katakana Editores). She now lives in Miami, Florida.

Images by Hayika Maras

Living Room Set

After

She was cremated,

I got rid of the living room set.

Two men carried off

The load of green corduroy,

Springs and foam.

The space was left empty.

I swept up flowers of lint, dust,

Hair, dead skin cells, fibers,

And a few insect droppings

Hidden for days

Under the two sofas.

The blinds

Remained open.

The mid-day sun

On the tiles,

Shined with

An unfamiliar clarity.

Then, as I got used

To that sunlight,

That vacancy,

That’s where she settled,

In the deserted room, the

Oblique afternoon light.

No one saw her. I didn’t see her either.

But there she was, quite small, subtle,

Omnipresent, filling the space left

By the furniture.

Juego de sala

Después que la cremaron,

Saqué el juego sala.

Dos hombres se llevaron

El cargamento de pana verde,

De resortes y espuma.

El espacio quedó desocupado.

Barrí las flores de pelusa, el polvo

Células de piel muerta, pelo,

Fibras y un poco de carcoma,

Escondidos por días

Debajo de los dos sofás.

Las persianas

Se quedaron abiertas.

El sol de medio día

Sobre el embaldosado

Brillaba con una claridad

Desconocida.

Luego,

Cuando me acostumbré

A esa luz de sol

A ese vacío,

Ella se instaló allí,

En esa habitación desierta,

En esa luz oblicua de las tardes.

Nadie la vio, yo no la vi tampoco.

Pero ahí estaba, muy pequeña, sutil,

Omnipresente, ocupando el vacío

Que dejaron los muebles.

Vegetation

Why do I see you

In the rough, dry earth,

Between roots

And odd kinds of soil,

That I cannot name,

Between lime and pieces of cement

Fallen on the ground?

Or between lizards and crickets

Jumping in the dust and weeds,

While you are ashes?

I tremble,

Because I feel you alive

In this microcosm of soil.

Because now you live in the vegetation …

Perhaps reborn in those pale roots,

Or scattered on the earth.

Vegetación

¿Por qué te veo en la tierra,

Áspera y reseca,

Entre raíces

Y formas irregulares del suelo,

Que no sé nombrar,

Entre cal y trozos de cemento

Caídos en la tierra?

¿O entre las lagartijas y grillos

Que brincan en el polvo y la maleza,

Mientras tú eres cenizas?

Tiemblo,

Porque te siento viva

En el microcosmos del suelo.

Porque ahora vives en la vegetación…

Tal vez has renacido en esas raíces pálidas,

O estás esparcida en la tierra.

María José Claros received her degree in English from the University of Alcalá, Madrid and continues to live and teach in the city. She has a deep love and interest in modern and contemporary Irish poetry.

mnx2ou

42tfho

3oi4xe