ANNIE BIEN

★ ★ ★ ★

FLASH FICTION

The South Middle Kingdom Sea

Daddy spoke about not speaking, about not wanting to remember but remembering. Mommy spoke about not wanting to remember, pointedly remembering to forget. Daddy’s eyes scanned through life episodes as he surveyed the backyard. Mommy dug weeds, her mind reminiscing the Fragrant Harbour, a reluctant memory. I watched my parents, absorbed in their unshared panoramas.

The neighbor’s cat crouched on the fence, eyeing the white rabbit, suddenly leaping after its prey. A long, high-pitched scream emerged from my baby rabbit who sprinted, crying for life not death. I pulled the sliding door apart, ran, shouting. The cat disappeared. I held my quivering bunny. How would I care for the Easter gift Mommy brought home on a whim?

“Maybe carrots like Bugs Bunny,” said Mommy, my still unnamed bundle shivered in the cardboard box. “Maybe this was a mistake. But I only paid a dollar.”

Bunny didn’t eat carrots but did eat carrot tops; he didn’t know what was good or bad for him. He was a frightened bunny; and I, a frightened girl. I wished I could turn the page to the end of Bambi when he was grown and wise.

My best friend had a rabbit, but I don’t remember the food inside the cage. She was long gone though. The longan tree dropped ripened fruit into the backyard, a sweet scent rising in late afternoon sun, trampled fruit eaten by squirrels, sticky on the shoes.

I don’t know how to take care of you, Bunny, what will happen, is this what happens when people don’t know do what to do, do they stand there hoping something will change without doing anything?

I watched Daddy reading the newspaper through the sliding door. My best friend’s rabbit had outlived her.

Mommy chopped scallions. She’d chosen to forget dirtying her face when she walked, escaping the Communists, escaping the Japanese, her toenails bruised black trudging day after day from where they could no longer stay, plodding to where they would arrive. Mommy thanked God, or was it Buddha, for not being beautiful; she watched women dragged away by men who foraged for bodies to molest, left bloodied, bruised, dead. Mommy blocked out the cries, the rotting flesh and feces, trusted her feet, made sure she smelled foul and silent, covered herself to look unappealing, maybe not even womanly, hiding food in her pockets, silent, her memory shaving sharpness to blunt as she watched, like a grazing impala on a savannah trying to see if it was time to run, stand still, or fall limp. Mommy squashed the memory of being cursed as bad luck by a fortune teller, abandoned by her mother, sent to grow up with impoverished relatives who fed their own son her monthly allowance. She grew up small, unfed, uncared for, until Grand Nai Nai interceded. These memories exploded when my brother and sister suggested Mommy wasn’t well, maybe had Alzheimer’s. Mommy asked me, “Please believe me, I’m okay?” I hugged Mommy.

Hidden deep in his pocket, Daddy withdrew a pocket watch with chain, something he’d never looked at in the open during the War, in case someone wrested it from him. Now he showed me: “This was your grandfather’s. I kept it because sometimes I just needed to know when it would all be over. Now I don’t need that. That was before you.” He held me tight.

Mommy fingered the wedding ring hidden in her pocket, so no one could cut her finger off for it. “This is the ring your Daddy gave me.” I knew she loved him no matter what she said.

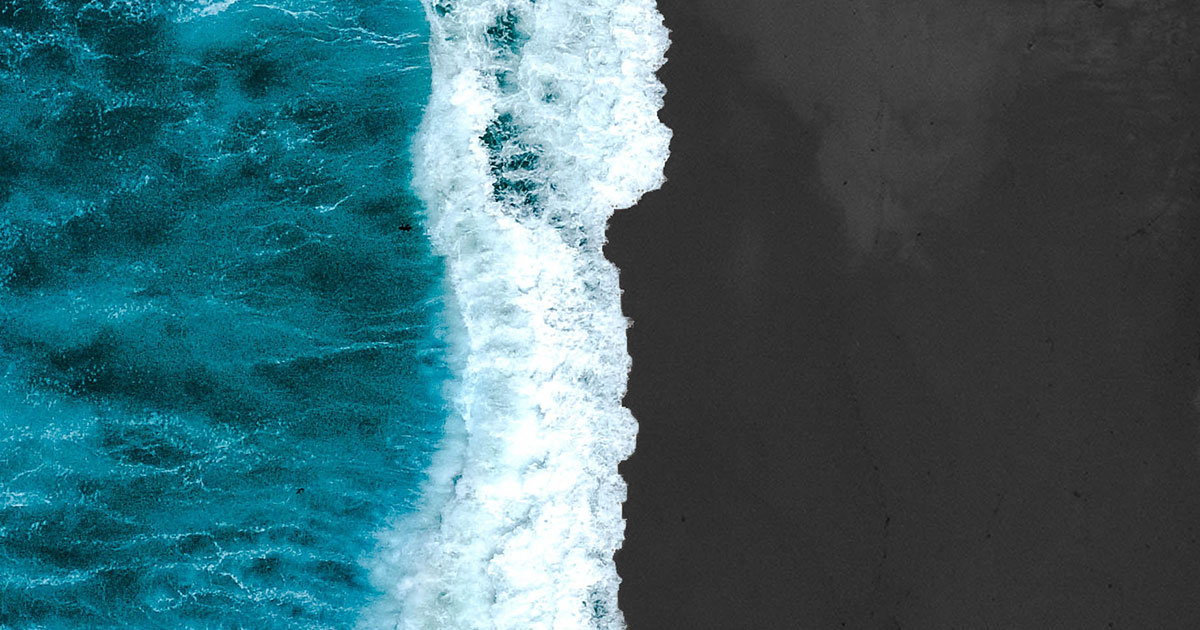

They’d witnessed people and animal bodies in roadside ditches, prayed to survive, to escape, to arrive where they’d rest their heads on pillows, sleep at night in quiet beds at the Fragrant Harbour, Hong Kong, a refuge island in the South Middle Kingdom Sea. The waves resounded with past, present, and future.

I went outside. Bunny lay on his side, panting, flat, draining heat. Then his breathing stopped, his body cold. Mommy pushed me aside, putting the rabbit in a shoebox, tying it, instructing Daddy and Bro to drive to the dump, throw it away. Bunny became valueless, first bunny, then rabbit, animal, shoebox—please don’t say, I only spent a dollar. I went too, maybe they wouldn’t dump Bunny, maybe they’d bury him. Maybe. But I didn’t say anything aloud, only wished it.

My brother pitched the shoebox into the sea of trash.

Forgive me, Bunny. Please. I wished bunny heard my apology as he was thrown through the air. I hadn’t given him refuge, given him a place to sleep quietly. Was it because we were landlocked?

May waves from our South Middle Kingdom Sea, known as South China Sea, still swarm and recede as before, harbouring hope in storms.

Image by Nicholas Vreeland

Annie Bien has written two poetry collections—Under Shadows of Stars (Kelsay Books, 2017) and Plateau Migration (Alabaster Leaves Press, 2012). She is a nominee for the Pushcart Prize 2020, has published flash fiction in print and online magazines and been a finalist and shortlisted with Strands International Flash Fiction, A3 Press and Review, and Reflex Fiction. She is an English translator of Tibetan Buddhist scriptures for 84000: Translating the Words of the Buddha. http://anniebien.com

DEAR READER

At The Wild Word we are proud to present some of the best online writing around, as well as being a platform for new and emerging writers and artists.

As a non-profit, the entire site is a labour of love.

If you have read the work in The Wild Word and like what we do, please put something in our tip jar to keep this amazing platform alive.

THANK YOU FOR YOUR SUPPORT!

As a young boy, I raised rabbits outdoors. One cold winter, a mother rabbit laid her babies in two different places in the nest I’d prepared. I didn’t know to move them together—mother knows best. But while she was sitting on the babies in one place, the others froze.

As a young boy I raised rabbits outdoors. One cold winter, mother rabbit laid her babies in two different places in the nest I’d prepared. I did’t know to move them together—mother knows best. But one night while she sat on one group of babies, the others froze.