FROM THE INSIDE

★ ★ ★ ★

FLASHBACKS

Image by Bernard Hermant

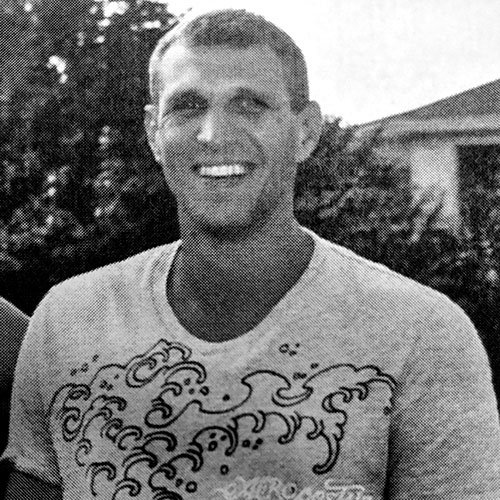

By Ryan M. Moser

I remember when times were easier. Taking a lunch break by the Delaware River and walking over to a shrub of canary-yellow trumpet honeysuckles. Picking one carefully and then slowly, methodically, pulling the thin stem from the blossom to reveal a small drop of sweet nectar that I put into my mouth. The August sun beating down on my bronzed arms. An Eagles song playing in the background from my parked truck as I look down the line of split-rail fence that my buddies and I just finished erecting.

They sit in the pickup bed eating lunch while I walk towards the mossy canal—the little brother of the meandering Delaware a hundred yards away. I drop down into the sandy silt banks and sift through the damp grit, looking for old arrowheads or a musket ball. I light a Marlboro and kick over a stone, searching for history. Think about my date tonight. I wade across the shallow canal and head east, making my way past gnarled pines and through a thorn bush (startling a white-tailed deer), past a rusted wheel well to the rope swing on the river bank. The dog days of summer are sweltering, and the woods are quiet.

I remember when times were harder. Standing in a row of inmates stripping in front of ten correctional officers on my first day in prison, getting lice powder thrown in my face and on my naked body as redneck guards with dip in their mouth spray curses and insults our way. A boy has his tooth knocked out by an obese sergeant because he doesn’t comply fast enough.

“Shut yer fucking mouths you cocksuckers and do what ya told!” the guard yells.

Walking through a metal detector in boxers, past a line of holding cells that smell like urine, the desperation of men being treated like animals filling the air. We stop at the next station for our weight, height, and age—tagged as human livestock to be warehoused, forced into labor, and abused until release into the wild or expiration.

I take my work boots and wet socks off, tossing them to the side, flick my cigarette and throw my tee shirt and jeans in a heap on top of a rotted stump. Standing in my boxers on the high riverbank and looking down, I grab the frayed rope in between my calloused hands and pull to test the old swing. Above me, the arching arm of a Pennsylvania oak bends out over the cerulean current, moving steady as I step backwards and jump up, letting my momentum carry me towards the flowing, ancient water channel born of the Catskill Mountains.

My bangs cover my face and the wind whips. I swing out to the end of the rope and let go, dropping into the cool expanse. When I come up for air, I plant my bare feet into the coarse and rocky riverbed, leaning towards the flow with my knees bent, water splashing off my chest into my eyes. I dig in against the strong current without worry. I’m 17 and have grown up here in this river. I will not be swept away.

The only worldly belongings I possess are stuffed into a brown bag that I clutch against my chest like a baby: toothbrush, toothpaste, soap, pencil, and one change of prison blues—shirt too big and pants too short. The guards spit invectives from the gun tower above, throwing trash down while laughing at the new fish. I quietly and secretly want them to fall to their demise.

There are no trees outside the razor wire fences, no landscape to be seen but russet dirt and brick and steel. The gates clink and clank open and close as we enter the block and I look around. My cell number is written with a marker on my bag, and I scan the cells for 13B—I’m housed on the second floor. I climb the metal stairs carefully with my chest out, surveying the residents and looking for threats as the guards back out and shut the gate amidst hollering and chaos. I’m 29 and worry about losing my first fight.

A boy drowned in this very spot many years ago, downstream from this murderous rope swing—I always wondered if someone had left it hanging out of memorial or forgetfulness. George Washington and his small army crossed the Delaware right here, 250 years ago. As I look around at the tree-lined banks of Pennsylvania and across to the foliage of New Jersey, feeling the rush of water against my skin, I realize that Washington’s crossing is my paradise.

Before I reach my cell door, I look down and see blood stains on the concrete floor. Bright fluorescent lights shine on the cavernous three-story block; I stop walking and look over the rail at men playing cards at tables, watching TV, and hustling in and out of darkened rooms. Cigarette smoke drifts upward and clings to the light ballasts like a cloud at twilight. No guards. No hope. Loud commotions and confusion permeate every comer as I step towards the opening of my cell.

Ryan M. Moser is a recovering addict serving a ten-year sentence in the Florida Department of Corrections for a nonviolent property crime. Previous publications include Evening Street Press, Storyteller, Santa Fe Literary Review, The Progressive, themarshallproject.org, medium.com, thewildword.com, thestartup.com, and more. In 2020, his essay “Injuries Incompatible with Life” received an Honorable Mention award from PEN America, including publication on pen.org. Ryan is a Philadelphia native who enjoys yoga, playing chess, and performing live music. He is a proud father of two beautiful sons.

This column was made possible with the help of Exchange for Change, a non-profit based in Florida that teaches writing in prisons and runs letter exchanges between incarcerated students and writers studying on the outside.

Exchange for Change believes in the value of every voice, and gives their students an opportunity to express themselves without the fear of being stigmatized. Their work is based on the belief that when everyone has the ability to listen and be heard, strong and safe communities are formed, and that with a pen and paper, students can become agents of change across different communities in ways they may otherwise have never encountered.

0 Comments