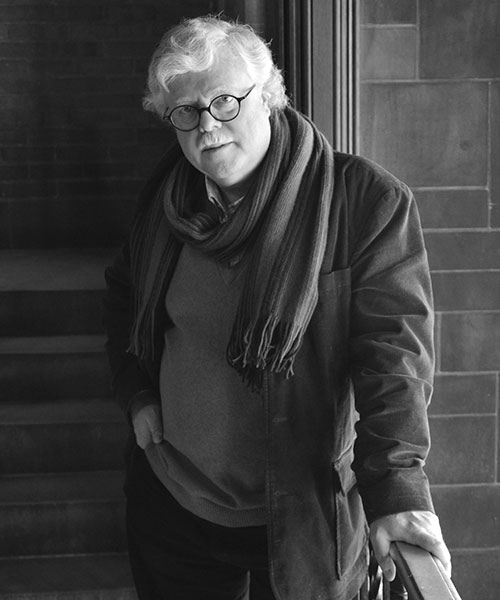

BRUCE MEYER

★ ★ ★ ★

FLASH FICTION

Image by Jordan Whitt

‘Aces’

When my brother and I were young, we were captivated by the exploits of the World War One fighter ace, Billy Bishop. He was a flier of our grandfather’s generation, and though the old man never spoke about his own experiences in the trenches, he would talk incessantly about Bishop.

Grandpa would tell us the tale of how the famous aviator had been posted to a squadron at the front, and how he rose before dawn on his final morning there. He would point a finger on his left hand at us – he’d lost most of his right hand in the war and wouldn’t talk about how had only a thumb and index finger remaining – and say, “Boys, bravery is doing what you don’t need to do. Billy Bishop didn’t need to get up in the darkest hour that day. He was going back to Blighty at eleven. But instead, he climbed into his cockpit and as the sun came up over the front, he shot up a German aerodrome and registered five kills before calling it a day.”

We asked him if he’d seen Billy Bishop during the war. Grandpa thought for a moment. His eyes darted back and forth. Then he nodded. Yes. He’d seen the famous flier. He’d looked up one clear spring morning and witnessed a dogfight above him. That was all the old man would say.

My brother and I found Bishop’s autobiography in the local library. I had just begun to read, and my brother would listen as I struggled with the words. We marveled at the passage where the ace recounted how he’d wanted to fly before the war began, how he’d built an airplane out of junk wood and orange crates and attempted to glide it off the slanted roof of his boyhood home. We decided we could do the same.

Bishop was lucky. He only broke his leg. In photographs, the great ace is pictured leaning on the wing of his Nieuport scout, and the walking stick he required is either settled on the silver wing or leaned against the fuselage.

The week our parents were away in New York, my brother and I figured out how to climb the tree outside our bedroom window and started hoisting found lumber into the tree with ropes.

The war had left our grandfather deaf, so the old man was none the wiser to the hammering on the roof. When we’d come inside for dinner, he’d ask my brother and me if we were behaving ourselves and remind us not to stray too far from home.

As our airplane neared completion, my brother went into our mother’s dresser drawer and found swim goggles and a yellow swim cap with rubber daisies garlanding the crown. I wanted my brother to turn the cap inside out when he flew – he had demanded to go first. I was to give the aircraft its power by pushing it over the shingles and past the eavestrough.

Our grandfather had a habit of getting up in the night and passing our door on the way to the bathroom, and on his return, he’d look in our room and check to make sure we were asleep. We thought we’d timed his trips according to how many cups of tea he’d had before bed, but that night we got it wrong. The sight of our empty beds panicked him.

He’d told us that empty bunks in the Officer’s dugouts signaled who had been killed or missing in action.

He saw our bedroom window open with the cool night air playing in the curtains. When Grandpa went to the window, he saw my brother fly past as our contraption dove nose-first into the yard. It smashed a wing against the tree on its way down and ejected him from the broken wicker lawn chair we’d cut down for a seat.

By the time I scrambled down the tree, my grandfather was already bent over my motionless brother who had a strange smile on his face, not of happiness but calm.

The old guy was weeping.

He kept asking why. He looked at me with a terrifying and accusatory intensity and muttered something about looking after the little guy and what on earth was I thinking.

Then he crouched in a ball next to my brother and shook.

The sun was coming up on the late summer morning but in the dewy air, I could see my breath. The grass glistened.

The yard was littered with broken lumber. My brother lay at an awkward angle and the strap of the swim goggles cut into the crown of rubber daisies. He hadn’t listened when I told him to turn the swim cap inside out to look like a real ace.

Bruce Meyer is author of 68 books of poetry, short stories, flash fiction, and non-fiction, and his stories have won or been shortlisted for numerous international awards. His most recent collections of short stories are Down in the Ground (2020), The Hours (2021), and Toast Soldiers (2021). In 2022 he will release two more collections of short fiction, Magnetic Dogs and Sweet Things. He lives in Barrie, Ontario.

0 Comments