MY FEMINIST MOMENT

★ ★ ★ ★

By Rebecca Menzel

My feminist moment hit me in a stressful traffic situation. I managed to hit a car while trying to park and had a confrontation with the driver in which he called me ‘a stupid, dumb woman’. The exchange left me stunned and I was so upset I ended up filing a defamation report with the police.

Even though I had made the report I was reluctant to stand in court beside an ugly-minded guy and tell everybody why his comments insulted me. It made me feel weak in a strange way, as if by appealing to the law, I was lacking in self-confidence. I felt a strong inner conflict with a feminist motivation. Somehow the idea didn’t connect with my self-perception as a modern, independent woman. But why did I feel that way? Is there a link between my personal idea of being a “modern” non-feminist women and the special history of feminism in Germany? What does feminism mean to my generation of women in Germany, raised in the 1980s, having benefitted from the achievements of the women’s movements, but still struggling between professional and family life?

My mother was a stay-at-home-mother all her life, busy with four kids. She describes her marriage as happy, but was well aware that her work at home was not valued in society the way my father’s career was. She has a bookshelf full of feminist literature that she acted out silently. She did not join in demonstrations, but she always urged me not to become financially dependent on a man. Despite this, that is exactly the situation I am in now. Working freelance with two kids and a husband who works full-time, I struggle to earn enough money to make a living of my own. I feel for my husband when he is stressed out from long working hours and doesn’t see the kids as much as I do. But at the same time I am often angry that I spend much more time on household and family organisation than he does. Did I unconsciously follow my mother’s life track, and lose my set path of self-determination?

The media upheaval for the “protection” of females after the violation of German women by foreigners during New Year’s Eve celebrations in Cologne started a moment of revelation. The whole “gender problem” was nullified by saying that gender equality is part of the German constitution. That argument denies the fact that neither German laws and enactments as a whole, nor the experiences of women in everyday life, correlate to the basic right to equality in an adequate way. I couldn’t help but wonder why nobody raised the question of existing structural gender inequality in Germany.

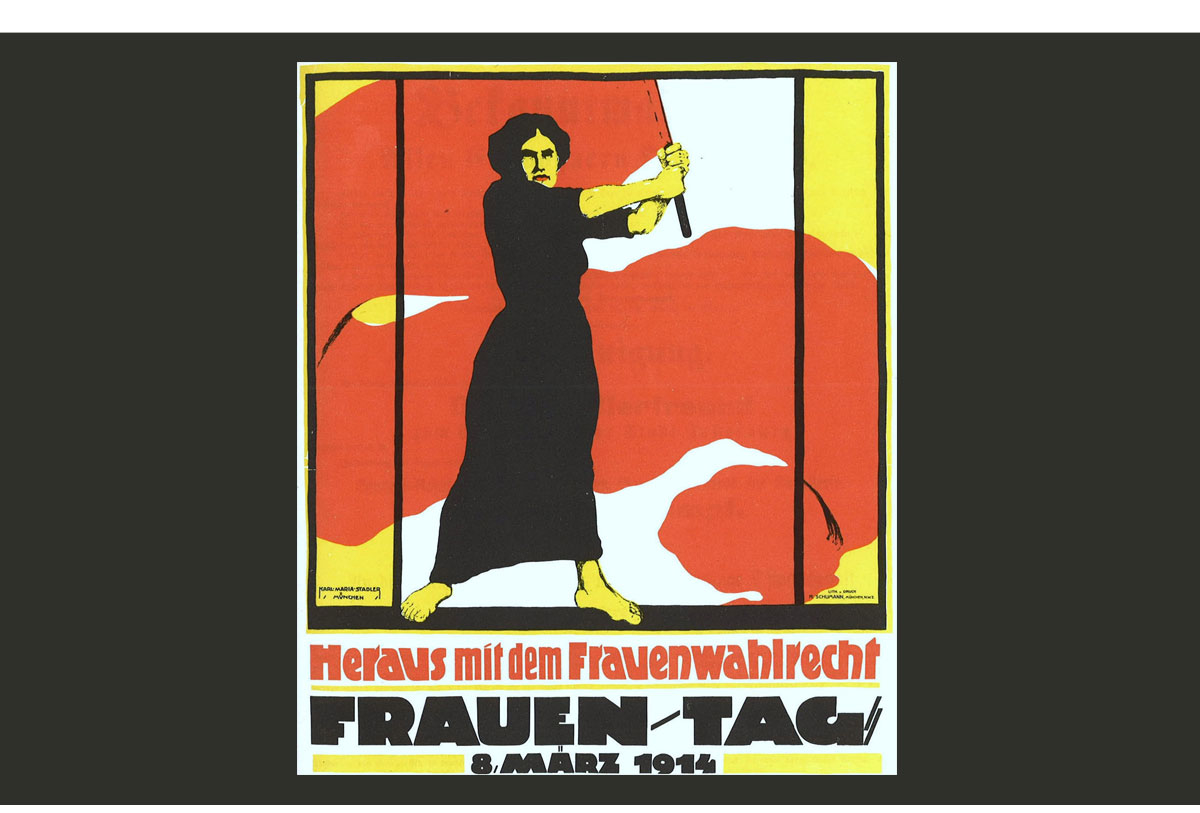

The strong tendency to marginalise feminist arguments against structural inequality in the German public debate has a lot to do with both the development of, and the persistent negative response to, the women’s movement right up until today. Since 1968, when female members of the Socialist Students’ Association (SDS) published a leaflet that showed an axe-carrying woman under a gallery of severed penises with the names of male SDS leaders, feminists have been classified as aggressive and politically disloyal. The campaign expressed women’s frustration that gender inequality was not seen as a major part of the leftist political fight against a bourgeois and patriarchal society. Conservative opponents succeeded in pushing aside women’s issues by referring to a popular communist threat, pointing out that the GDR forced women into the labor market. Caught between political ideologies, leftist women interpreted motherhood as a hindrance to political dedication, which cut them off from a positive perception of family life. The fight for legal abortion that dominated feminist debate in the 1970s united women from different political viewpoints in a broad protest movement, but at the same time promoted the belief that feminism was mainly a matter of individual sexual freedom. The major changes in German legislation that have had a much greater impact on women’s everyday life, like the 1976 reform of the marriage act, passed somewhat silently. This lopsidedness in the public perception of women’s issues has prevailed today. Feminism still has a tangy smack in Germany, which makes it hard to connect to a worldwide discussion about the interference of gender roles and social criticism.

Just recently the German weekly newspaper Die Zeit offered an interesting inside view of a gender discussion in their editorial department. They had planned an article about their personal struggle between family life, relationships, and work. All the female journalists refused to contribute, deeming it too private an issue. None of them thought it would be worthwhile to take up the mantel of the past or present women’s movements. In the end, the two male journalists wrote an interesting piece about being a father and of always feeling insufficient. They received enthusiastic letters from the readers. What was more interesting was their retrospective opinion that the “forces of society” are too demanding to allow the cutting back of working hours. I ask myself if someone with a feminist perspective would have argued the same way. I don’t think so.

Often both men and women today try to cope with working in highly competitive fields that don’t go well together with family life. Many couples feel how the pressure of competing in the professional field impacts their private life when they argue about who invests more time in washing, doing the dishes or helping the kids with their homework.

Gender inequalities still have a strong impact on our daily life, especially if you look at persisting wage differences. Women still earn 20 percent less than men. Studies show that the main reasons for the gender pay gap are continuing gendered career choices. Women still predominantly do the lesser-paid (social) jobs, while men do the better-paid (technical) ones. Another reason is that maternity leave still means a severe setback for a women’s career. Women with kids more often work part-time, and even if they work the same hours women don’t get the same pay because companies silently make the assumption that they don’t work as effectively as men. Many women try to cope with the time-consuming requirements in highly competitive fields, where they are confronted by work standards often set by men who don’t suffer the same pull between home life and professional life. Studies show that women still invest much more time in family work than men. If they fail, they often hold themselves responsible, not the system.

In times when global competition and self-determination feels like a mantra, it is hard to think about consciously opting for less in a professional career, for both men and women. That’s where modern feminism should step in.

Rebecca Menzel is a freelance historian and journalist and published a book about jeans in the GDR. She now works on her dissertation about alternative lifestyles in FDR and GDR.