FROM THE INSIDE

★ ★ ★ ★

THE POWER OF FRIENDSHIP

Image by Ire Photocreative

By Marina Bueno

Evenings are mayhem in prison dormitories. There are showers running, TVs blasting, radios booming and conversations occurring. Even in the quietest dorms it is hard to hear the person in front of you. A dull roar.

That is until the officer announces “mail call!” Then all conversations stop mid sentence: TVs are turned off, radios extinguished, eyes fixed on the officers holding a stack of envelopes.

It doesn’t matter if you’ve never received a thing, if night after night your name is never called. There is always hope that one of these days you will be one of the lucky.

One day, it was my turn.

But the return address was unfamiliar – not from my parents who have written to me regularly. It was a name I did not expect, Noel. He’d been my best friend in high school. The weight of the envelope was incomparable to the weight of the shock that I felt. I took the letter into my room and stared at it for a while before opening it, thinking back to the first day we met sitting in a booth of Scorekeeper’s Sports Restaurant.

I don’t remember what we talked about but after that day we were best friends. Our lives converged and abated countless times throughout decades. Life blew like a calm breeze and battered us like a hurricane in turns.

I flew in and out of his life on missions – chasing any and all of the vices that the world had to offer, girls, booze, drugs. Going off radar for months until I landed in the mess I was in now.

I hadn’t been in touch with Noel before my incarceration, nor had I heard from him in the years I’d resided in custody. My parents told me that there were some mean posts on my Facebook page about me getting locked up. I was ashamed about the state of affairs of my life so I accepted that I wouldn’t be hearing from any of my friends. I hoped that everyone would forget who I was.

I didn’t want to open the letter. I was afraid.

Holding Noel’s letter I was ashamed. I thought about all of the things he had to see me go through, all of the destructive, drug-induced behavior. I cringed remembering that I had been a mean and ugly person. I dreaded that he would echo all of those thoughts.

But on one page I got none of this. He wrote to me to say hello. He wrote to me to say that it had taken a long time to write because of life and he hoped I’d write back.

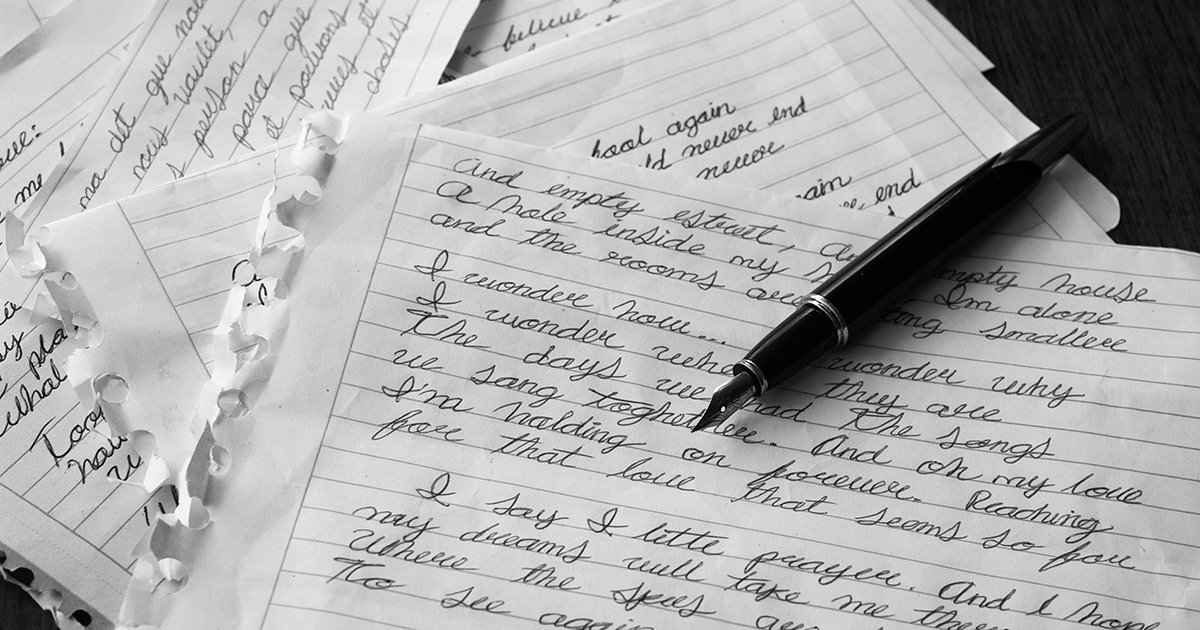

I began my letter by apologizing for sounding weird. I told him that I’d missed him. I missed knowing someone that remembered me before the uniform. I was sick of being by myself in my head. I asked about the others, the other friends who didn’t come around. I wrote a short letter so I wouldn’t freak him out with the twenty page letter that I actually wrote but didn’t send. And I sent it that same night so that he would get it quickly.

Noel was the first person on my visitation list that wasn’t my family. We wrote back for some years until life got a hold of us both and I hope that life will spin us around in each other’s paths again.

Corresponding with him helped me a lot. It forced me out of the head cave that I languished in, spinning around like a dog tied to a short tether in a yard carving a track in the furrowed ground.

It is not just the barbed wire that holds me but the grey wrinkles that grow up around the pictures of the past in my mind. It is how shame shapes memories, making them the ugly movies that play on the back of my eyelids late at night. They change the good, turning them into the same weapons that I punish myself with.

It was nice to have someone, even for a moment, not to tell me that those stories weren’t true but to assure me that despite how it was and how it ended, I could still be a friend through it all.

Marina Bueno is a Cuban-Russian immigrant that was raised in sunny South Florida. She’s been published in Prisoner Express, Prison Journalism Project and Scalawag. When not obsessively jotting down ideas and stressing her editor, she enjoys reading science and fantasy fiction, taking long walks on the recreation field with service dogs in training, and peer pressuring her fellow residents in prison to take Exchange for Change courses. She’s been incarcerated for 15 years and has a huge backlog of journals from which to pull material for her column From the Inside.

This column was made possible with the help of Exchange for Change, a non-profit based in Florida that teaches writing in prisons and runs letter exchanges between incarcerated students and writers studying on the outside.

Exchange for Change believes in the value of every voice, and gives their students an opportunity to express themselves without the fear of being stigmatized. Their work is based on the belief that when everyone has the ability to listen and be heard, strong and safe communities are formed, and that with a pen and paper, students can become agents of change across different communities in ways they may otherwise have never encountered.

lxcvg8

y9x6hx

ml03w2

ghgdxr

4f1bxd

9u3bss

5gepiq

9wyeie

vd5dnh