THE DEEP END

★ ★ ★ ★

Essays from the depths

By Richie Heffernan

About a year ago, before my family and I left Dublin for Berlin, I woke one morning in a sweat, repeatedly and urgently whispering the name ‘Kropotkin’ into the early light.

I had no idea who he was, but I’d just come from a dream of persecution, imprisonment and exile in which I’d been him. Rather like watching myself as Ben-Hur instead of Charlton Heston, but unfortunately I’d woken early and missed the conclusion.

Mystified, I was convinced something life changing had occurred in my sleep, but that waking had let slip away.

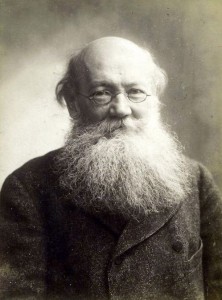

The name was surely too specific not to be real. I looked it up. Pyotr Alexeyevich Kropotkin (1842-1921), a Russian prince, scientist, writer and philosopher, who after declaring himself an anarchist at the age of 30 lived a long life of imprisonment and exile before returning to be feted in post-1917 Russia.

It had been a year of nightmares. Nearly every night I woke disturbed by increasingly black visions of the world in which I had somehow failed to avert disaster or apocalypse. We were living next door to my wife’s parents in the same type of suburban house I myself had grown up in. Renting with an agreement to buy when the landlord was ready to sell. He’d lived there with his wife until she’d died a few years ago, then remarried and moved away. He offered it to us for reasonable rent so we could start saving in earnest for a deposit.

I can’t say it was what I ever wanted from life. I had imagined more. Row after row of characterless housing, devoid of playgrounds or any culture other than that on offer from TV or the local shopping centre was certainly less than I’d dreamed of, but after years of trying to work up some sort of alternative I felt myself beaten into submission by the property speculators and policies that consistently denied us the chance of a decent home.

But the fact was our kids were growing fast and they needed a stable place to grow, as we’d had ourselves. So the offer of the house seemed a blessing. My wife would be close to her parents, my kids would have a road to play on and we would have a community. So we saved hard and got on with life.

One night, a couple of years later, the landlord announced he wanted to meet us and we started frantically preparing for an offer. I’d recently been to a Bowie exhibition in Berlin that had tantalised me with the possibilities of a creative existence. I’d bought the catalogue, come home and opened it up in bed some nights later. The first random page I read spoke of the suburbs being the death of the soul. Shortly after I had my dream of Kropotkin. It was becoming increasingly obvious that I was worried this decision was going to cost more than a mortgage.

We met the landlord and his wife, all smiles and best behaviour, only for him to announce he’d changed his mind and wanted to move back in. It was one of those moments when you watch the course of your life diverge from all previous expectations. My wife was absolutely heartbroken. I was upset for her and very angry at the betrayal, the security of our entire future yet again premised on some fucker’s whim. She really felt at home here, it was at the core of who she was and how she felt about herself. It was a working-class community with a strong sense of solidarity and it was the road she’d grown up on.

I’d spent the first ten years of my life in a lower-middle class estate half a mile down the road, which had been far less connected. The houses were the same in every respect, by the same builder, except with a square metre of stone cladding by the hall door as a marker. Many of its residents had aspirations of trading up.

In contrast, few ever left the road my wife grew up on, nor saw any reason to do so. They had all started out together as part of a purchasing scheme run by the council, partying hard through the formative years of the seventies as young parents with kids who had the run of the place. Dads finished their long shifts in the pub, while mothers juggled part-time work and full-time parenting, managing through tea and gossip as they passed round the valium so readily prescribed by the local doctors of the time. Nothing was or could be hidden, the transparency and honesty often brutal, but there was also a corresponding lack of shame.

At a glance many of the kids might have had a slight air of neglect about them with education somewhat incidental. But the stability and freedom of the road and its surrounding lanes gave them the measure of themselves, laying down the rules and codes that would matter for them. They were raised with a strong sense of who they were and who they weren’t – solid, well-turned out on a Sunday, and sure of no more than a few hard slaps from parents who provided unconditional love and support to their own, no matter what might befall them in life. There have been casualties along the way, but no more than from any middle or upper class area of comparable size. In that regard they have much the same story to tell. Most have ended up meeting the expectations they, or their parents had of their lives. And there’s a quite practical streak of not believing the bullshit, even when it’s not. What they have works and provides for their happiness as well as any other, a conviction that things won’t get appreciably better no matter what you do. That nothing comes without a cost.

And as the community has aged, with the urgency of their earlier lives receding, the essence of the road has declined. TV has something to do with it. As does the housing bubble, with kids driven elsewhere by inflated, impractical prices, and now the old magic is only seen on Sunday visits, funerals or the rare party sing song. As if a giant syringe has been slowly and quietly sucking the vitality out over many years.

But it’s also life; they’ve gotten old. A few are still working in their seventies or help out with the grandkids, but for many, the daily visit to the shops or the increasingly frequent visits to the doctors waiting room have now become the only social highlight in a backdrop of quiz and antiques shows. And as they slowly die, the dynamic communion of their productive years is being replaced in fragments by newcomers too overwhelmed with their mortgage and childcare to sustain their own. And what’s left in many respects is more of a remembered or imagined community. But then so, I suppose, are they all.

In her teenage years my wife wanted nothing more than to get out of there. She felt defined, but also trapped, by the lack of vision she felt her community held out for itself. But as the years went by, and we had kids of our own, those values seemed to increasingly appeal to her. By the time we’d tasted some of the less palatable housing possibilities that the Celtic Tiger had to offer, she was happy enough to head for home.

I grew up with parents who permanently aspired to more. Strong believers in education as the great improver, they switched me from the local mixed school at age seven into a private Catholic boys school in the city centre that was straight out of Dickens.

My Dad was a painter/decorator who worked long, long hours all through my childhood to fund that education and the bigger mortgages they had to sustain as they climbed the housing ladder. Theirs was a different sense of community. It mattered more to them what other people thought and as a result they were more private. Appearances mattered. Troubles weren’t shared or admitted to, with a resulting pretense that could be very isolating. There was, of course, a profound love, but a notion that you could only ever really depend on or trust your own, and that the rest of the world was to be guarded against as you plotted your way forward.

As an inherently open and optimistic young lad I found this worldview crippling. My education stifled and terrified me and I became increasingly detached. By the time my parents settled in their final home, I began to search for more. Largely managing to avoid the more serious consequences of drugs I had used, I turned instead towards anarchism. Not the Sex Pistols crap, but the sounds and art of a band called Crass, pacifists who mirrored how I felt about the world – mesmerisingly cynical, an acute sense of injustice and a conviction in getting things done. These were bullshit detectors I could respect, possessing a streak of self-righteousness that bordered on English puritanism. On their album covers, works of art in their own right, was printed ‘Pay no more than 99p’, an instruction ignored by every record shop in the country.

They perfectly mirrored the increasing rage and rebellion I felt against the expectation of all the adults around me. Actually when I first heard their music I was quite shocked, but my parents were so appalled that it seemed something was right. I had had no idea that something so base could be classed as music. But then that was the appeal – it was something I could do myself, as had the hundreds of bands across Britain signed to Crass’s label. Like the Great Leap Forward, lack of experience and skill could be overcome through sheer will and creativity. Fervent belief and action would make a thing real and you just made the rest up as you went along. While it might sound redolent of Thatcher’s bootstraps philosophy, its difference was the re-imagining of a sustainable collective of individuals rather than an individual at the expense of community.

This was an era when the ideas of things I intuitively cared for – relationships, people, community, were being routed by the prevailing culture of greed and selfishness; a culture proudly espoused in the pedagogy of my upstanding school and (in fairness to them) unconsciously propagated through the aspirations of my parents. And I had a growing sense that I was being groomed in service of this culture, that I was being set up. There was a keen sense also that Ireland was in many respects a failed state, that many of us would have to emigrate – at tremendous cost to ourselves, and our communities.

Though punk’s rage and narcissistic energy had long burned itself out, it provided a surrogate for me as I found the faith to turn from that path my upbringing had set out for me. Crass were a primer for some things I had never known or been taught in my apolitical household – feminism, ecology, sustainability, activism, anarchism and the courage of difference.

We had very difficult times in our house as I learned what these concepts might mean in my life. It caused the most terrible hurt for all of us and really took everything I had to hold out for my sense of self and not warp or buckle under the weight of expectation. I hated every fight more because it hurt my parents so, and to see the pain and confusion of their whole being as they essentially just tried to be true to what they felt was the right thing to do by their kids.

I always had a keen and sensitive understanding of this. I was a very outward-looking teenager, not at all selfish or self-obsessed, and this felt like a wider drama we were all caught up in, the working out of generational stuff, and me being the first-born made it all the more difficult. It all came to a terrible head one day when they decided to clamp down heavily and threw everything I owned that they disapproved of into a big black sack. It was crazy – like that film Footloose where the town passes a law against kids dancing. In that moment I knew if I was to survive with my sense of self intact I would have to escape.

I plotted, patiently hanging on until my final day at school and then bolted to a squat in London and self-imposed exile. It was an act of faith that took me right to the edge of my existence, broke my parents’ hearts and took years for us to recover from. I quickly discovered exactly how fickle the alternative to mainstream community can be. Within weeks I was robbed, beaten, homeless and broke. Peace and love my arse.

And yet, this time on the streets proved to be the most exuberant of my life – in casting myself adrift from all expectation and responsibility, I found warm companionship with others who’d done the same. A cast of characters, chancers and underdogs, some with very real reasons to forget, some just out for the craic. It was the late eighties and in the wake of a significant economic crash that had just torn through the city of London. It was also a time of such inequality that we felt no shame in our status. We’d spend our nights tapping a few bob and drinking around the streets of Soho, and it felt like we’d the run of the place. I’d never felt so free. Even after ending up in jail one night after giving out to a bobby over someone’s arrest, I felt no fear, with the scores of elderly homeless I met in there, all arrested for begging, just confirming my sense of indignation at the system.

I learned there to make a home in the comfort of my own daily routines and rituals, in my sense of self. I was never short of company – friendships of convenience, many of which filled the glaring void where family used to be. And while it opened my eyes, I knew I couldn’t be there for long. The shock of meeting many who were plainly gone, never to return; young girls and boys who’d turned to sex and men and women aged and ravaged by their demons and the rundown of the state; in time lost to drugs, disease or the cold.

When I could bear it no more, I scrounged my fare home from the Irish centre in Camden and came back to Ireland to try my hand at art before returning to London a couple of times and then on to a German commune for a couple of years before variously devoting myself to music, politics, social work, philosophy, film, cabinetmaking, sculpture and a host of other interests.

But always Ireland beckoned. Something called me home. Then sometime late in the evening of the 5th December 1996 my younger brother Barrie and his friend Gavin died of a methadone overdose. They were found in his bedsit a couple of days later by a friend. It was Barrie’s first home away from home and he’d been there a month. He and I were very close, yet I had had no idea of his problem. He’d hidden it well from me and I’m still in shock.

His loss destroyed my parents. Our Dad declined quickly and visibly and was little more than a shell of himself before losing his own life on a beautiful August morning a few years later, when his bike went under a truck on his way to work. He died at the scene, not much more than a stone’s throw from the house. His sandwiches that he made for lunch still lay on the ground when I arrived some hours later. We had long since reconciled and had also become very close. Despite having just previously become a father myself, I felt very alone in the world for a long time after.

Our little family stayed with my mother nearly every Friday night for the following eleven years, until our move to Berlin. Her home has been her greatest refuge through her grief and the connection and routine of our visits have helped us to live with our own.

All through these years my wife and I both looked on in dismay as the boom-and-bust economy denied thousands of us, of our generation, of our rightful place at the table. Many like us, who were forced to rear families in a climate that was intolerant of families, to pay criminal childcare costs while servicing mortgages that entailed a lifetime of disconnectedness from family. My wife and I chose differently from many – we didn’t go for the childcare, instead we tried to keep one of us at home for the children, but as a result couldn’t raise the inflated price of a home.

I’ve never given up on my belief in the power and possibility of difference, that diversity is our strength and the fountain of our inherent creativity and that our belief in better might win out in the end. The punk dream, the idealist’s dream. And also as I found out, Kropotkin’s dream – the belief that cooperation rather than competition could secure the long-term existence of humanity in this world. He renounced his title for it, turned from the path for which he was reared and then paid with a long life of exclusion.

Things have changed much since his time, and also indeed since Thatcher’s heyday. Our murderous dance with capitalism has perhaps now brought our species to the edge of extinction. I bring my children up on a planet where it’s commonplace in our culture for them to imagine no home at all for humans on the planet due to our blind commitment to competitive growth.

My upbringing always warned me not to stray from the path, and would no doubt have viewed the man who came to me in my dream last year as a harbinger of darkness, a bogeyman. After the fiasco with the landlord we decided, after many years of visits, to try and make Berlin a home for our hope and as a place to try to renew a sense of possibility for our somewhat fragile selves. And while it hasn’t been easy, as the song goes, we’re willing to give it another try.

Richie Heffernan is an artist and writer. From Ireland, he now lives with his family in Berlin, Germany.