ARTIST-IN-RESIDENCE

★ ★ ★ ★

MARIANNE SZLYK

We love artists at The Wild Word.

Our Artist-in-Residence page provides a space for artists to showcase their work and to spread their creative wings. In their month of residency, invited artists are encouraged to collaborate with other contributors within the magazine, to experiment and develop new projects, while giving us an insight into their creative process.

Our THE HEAT OF THE SUMMER issue Artist-in-Residence is poet Marianne Szlyk.

Marianne Szlyk is the editor of The Song Is…, an associate poetry editor at Potomac Review, and a professor of English at Montgomery College. Her second chapbook, I Dream of Empathy, was published by Flutter Press. Her poems have appeared in a variety of online and print venues, including Silver Birch Press, Cactifur, Of/with, bird’s thumb, Truck, Algebra of Owls, The Blue Mountain Review, and Yellow Chair Review. Two poems have received nominations for Best of the Net and a Pushcart Prize respectively. Her first chapbook is available through Kind of a Hurricane Press. She hopes that you will consider sending work to her magazine. For more information about it, see this link: https://thesongis.blogspot.com/

Writing Poetry in the Summer

When I started writing poetry in 2011 after two years short of a quarter-century break, I promised myself that it would not interfere with teaching, that, during the semester, I would concentrate on my students and my classes. As the summer draws to a close, I feel antsy about my writing. I know that I do not have much longer to draft poems, so I jealously guard my time. Yet I worry that I will feel the urge to continue writing poetry even when the semester and its five classes start. Coming at the end of the summer, being an artist in residence becomes both blessing and curse. Of course, I want to be able to make the most of this opportunity, but I worry that it will take time and energy from starting my five classes, easing my students into the semester, and participating in the service activities that the department and college always seem to come up with each year.

For the most part, my poems are summer poems, conceived and birthed during this season. As I tend to write in season, these poems are about the summer as well. For some poems, this means the freedom to travel. For others, it means the suburban and urban nature that grounds them. For still others, summer signifies the claustrophobia I feel when I hide away from Maryland’s heat and humidity—and the anxious frustration when I emerge from my house to crawl to the gym, my father’s, or Metro. I would wish for fall’s cool and crisp weather, but I do not have time to write in that season. My escape from the heat is writing about summer further north. (I haven’t tried writing about other seasons. Strangely enough, it feels like cheating for me. Although I do not write haiku, I admire its grounding in each season.)

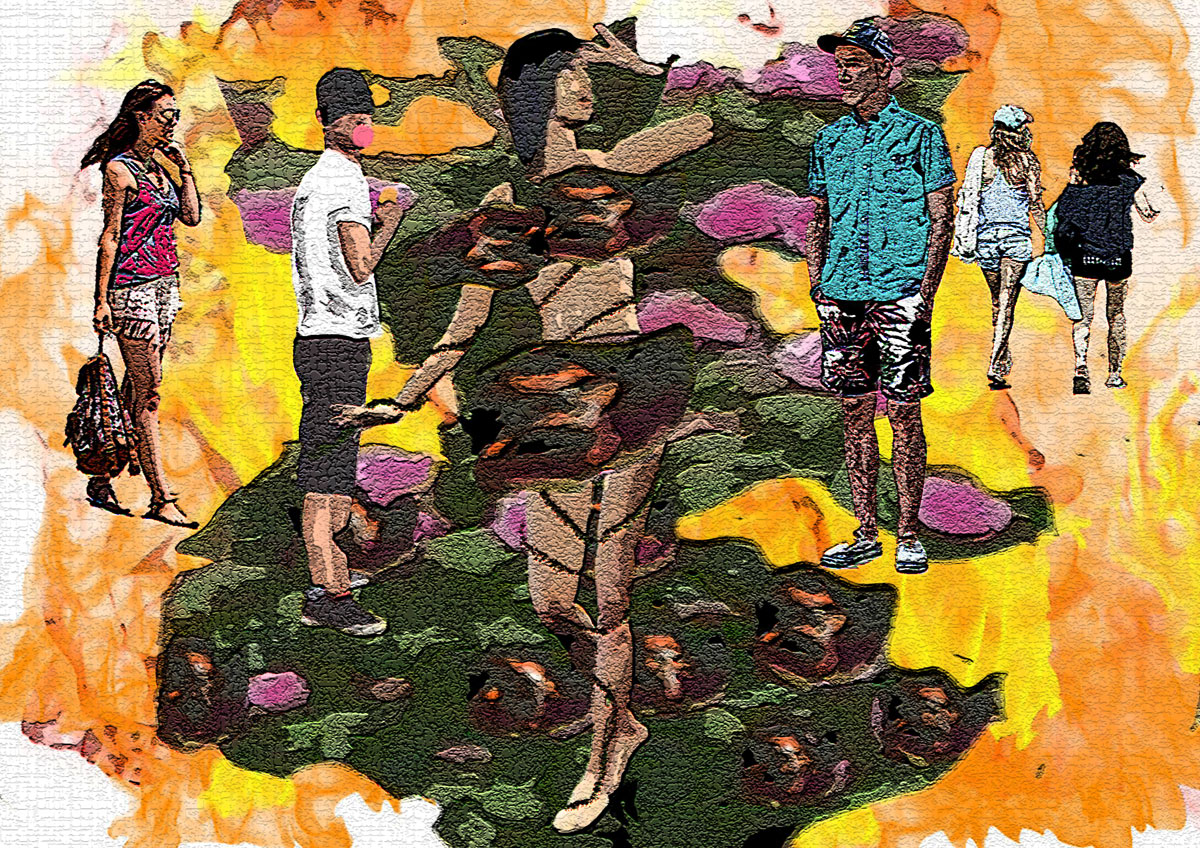

The Wild Word’s theme “The Heat of the Summer” compelled me for all of these reasons. “Fusion #1” depicts the worst weather of summer, when the heat tortures me—and the people who walk the other way seem unaffected. They may even be wearing jeans! Furthermore, most of the people in my neighborhood have darker skin than I do, so sunlight is less fraught for them. For me it means worries of blotched skin, skin cancer, and melanoma. “Tonic” portrays summers in New England where I grew up, as well as the transition from childhood to adolescence. In childhood, one’s family shapes one into an individual, but as an adolescent, one becomes more typical, wanting the sun and fun that everyone else seems to have, submerging one’s identity and desires into those of the crowd. The Seekonk that I imagine in the poem may have more than a little Southern California in it, but more of the Southern California one sees in reruns of shows from the 1960s and early 1970s. I wouldn’t actually see that part of the country until I was a young adult traveling to grad school at the University of Oregon, and even then only from a train window. Finally, “Music for the Drought” reflects my response to Miles Davis’ late album Amandla in the morning of another hot day. Who knows how the music would have sounded if I had been able to write a poem in another season?

As you may have guessed, summer is not my favorite season. Before I became an academic, I preferred taking my vacation in the spring or fall so that I could spend my summer time at work in the air conditioning. Even now spring is my favorite season. I love how the day lengthens. I love seeing first the forsythia and crocus, then the surprisingly early magnolia blossoms, the leaves of maple and tulip trees, and finally roses and irises appear in my neighborhood. Fall is my favorite season for fashion as I enjoy wearing tweeds, wools, jackets, long skirts, jeans, and even boots.

However, summer is more than just the tension between vacation and weather. Writing in the summer gives me the opportunity to explore different topics and then to wipe the slate clean in the fall. Looking back on each summer’s batch of poems, I see how my approach varies from year to year, taking on different topics, perspectives, and even techniques. Reading over my earlier poems, even poems from last summer, I realize that I have written fewer persona poems this summer. I continue to write in third person, but fewer fictional characters inhabit my poetry these days. Despite these changes, place and environmental themes have always been especially important to me. Unlike many Americans, neither my husband nor I own a car. I have never learned to drive. Instead, I walk a lot. Walking around Rockville, I have become concerned about our environment and climate change. Rising temperatures and erratic weather patterns make it more difficult to get around in a landscape that is more suited to cars than to people. It is true that Montgomery County does have a good public transportation system (for the United States), but sometimes it is easier and more pleasant to walk. I also wonder about the impact of future climate change, especially the rising sea levels and changes in plant life, some of which we are already seeing.

Last summer I began my experiment with counted verse, focusing on the number of words in each line. Most of the time I limit the words in each line from my very first, handwritten draft. I find that this structure enables me to polish my poem more quickly. After all, the format is set. At first, I also worked in two and three line stanzas, lacing the poems into a tight structure. This summer I am continuing to work with counted verse, but the stanzas are more irregular. Some poems are even one unbroken whole. “Music for the Drought” appears to be a throwback to last summer since I am experimenting with haiku-stanzas. Counted verse gives my poem a certain structure, but I am also beginning to question its limits. “Tonic” began as counted verse, but, during one of the later drafts, I changed the line breaks to something more organic. “Fusion #1” never was counted verse. It began as a prose poem. Perhaps next summer I will try something different. After all, I will be wiping the slate clean at the end of August.

Image by Ashling McKeever

Fusion #1

The act or process of liquefying or rendering plastic by heat

She knows it will never be hot enough to melt plastic,

but this humidity is like a shopping bag

melting around her face and arms.

Fumes bitter the air. Sky and earth

barely blot out the liquid. Soon

acrid waters will rise from the lawns

but not fall from the skies.

Marigolds and asters become hard to the touch,

break off like the fake flowers

in her mother’s closet. Pink roses melt

into brown goo. Their bush withers

to a thorny stick.

Her bones and marrow melt

as she inches home, much more slowly

than her usual clip.

Teenagers bounce past her, eating

orange potato chips and drinking

radioactive yellow sports drinks

from the Chinese bodega.

The girls bubble up like soda,

checking the latest social media.

They resist this fusion.

She cannot.

Image by Juan Tituana, Copyright 2016

Tonic

Chiefly Eastern New England: soda pop

Morning thunderstorms keep us home,

away from swimming lessons and

the round of suburban errands.

Heavy, buggy clouds rumble;

lightning flashes beyond the pines.

Yesterday’s humidity still clutches at us.

My mother sends my brother

to the basement to shut off

the electricity. The fan sputters,

then dies. We listen

to a transistor radio.

Jagged static interrupts

last summer’s soft rock hits.

I sneak diet ginger ale

before it is tepid and flat.

Next summer I’ll be working

for my father in the city

in the air-conditioned,

windowless office

on Dorchester Avenue.

Drinking icy cans of Pepsi

from the corner store,

listening to the Providence station,

I will imagine summer in Seekonk.

It blazes with classic rock

and feels as smooth as coconut oil

while storms keep my brother

and my mother home.

Images by JD Moore, Copyright 1992

Music for the Drought

After Miles Davis’ Amandla

Metallic trumpet

rises like heat mirages

over cracked asphalt.

echo like the sidekick’s fingers

on his closed window.

a blank land before breakfast.

Mountains are just haze.

days away from this road trip.

Keyboards mimic rain.

Miles’ trumpet scorches white

earth one cannot own.

The Song Is…—Reflections on a Blog-zine

Just over two years ago I began my poetry (and flash fiction) blog-zine, The Song Is… Since then, it has served many purposes. It has honored jazz musicians, both classic and contemporary figures. I am especially pleased by the work that poets Felino A. Soriano and Bryn Fortey have done, drawing readers’ attention to a wide range of musicians from Marian MacPartland to Charlie Haden to Lil Hardin (Louis Armstrong’s second wife) to British saxophonist Kenny Graham. Kerfe Roig has united words and images to honor Sonny Rollins and other greats. I have also met many poets and expanded my own poetry through this blog. Angelee Deodhar has encouraged me to explore the haiku and haibun, and she has turned some of my poems into haiga. Will Mayo has noticed some trends in my work, which I will talk about in my reflections on environmental poetry. Reading Felino A. Soriano’s work has given me enormous respect for his tremendous work ethic and a broader idea of what is possible in poetry. Finally, I must mention my epistolary friendship with the inspiring Mary Jo Balistreri and with Catfish McDaris who has judged a number of my blog-zine’s contests.

However, I am also proud to say that I have provided a venue for a variety of poets, including emerging poets, some of who were my students and some who live outside the United States. As an educator, I recognize that we have to support and encourage emerging writers. Without support and encouragement, there will be no next generation of poets. Moreover, the support that I have received over the years has shaped my ideas of what I could do, as well as what I actually did do.

Even if I weren’t an educator, I realize that I have reached the time in my life when I must also be a mentor. Belonging to the D.C. Poetry Project and the D.C. Poetry Spot encouraged me to create a heterogeneous community of poets. Both of these poetry groups bring together expert and novice poets for writing, performance, and fellowship. Inspired by these groups, I seek to curate a blog-zine that is welcoming to a wide variety of poets. Sometimes this is a struggle as I worry about the balance of poems, but overall I like to think of my site as an online version of an open mic. Moreover, I believe that novice poets can learn from the expert poets among them.

Fairly early on in my blog-zine’s history, I invited—probably urged or even begged—my former student Eric Lloyd to submit a poem. When Eric was in my creative writing class, his stylish poetry impressed me. I was particularly excited by one poem set on a treadmill as he ran to the electronic music of Swedish House Mafia. As a result, I let him know that I had started a blog-zine and was looking for poems. He sent me this wonderful poem—“Jazz Most Elusive”.

Amber Smithers and Alex Conrad, also former students, have appeared frequently at The Song Is… Amber, in fact, began on a high note with “A Lullaby to My Son,” an entry in a contest for political poetry mourning the death of Michael Brown. (By the way, Amber’s poem won).

A Lullaby to My Son

Hush little baby,

Don’t you cry.

Mommy’s not gonna let you die.

Don’t let those demons

Take your light.

I’m sorry I wasn’t there that night.

But now mommy’s gonna win this fight.

Mommy’s gonna love you through the night.

Hush little baby,

Don’t you cry.

Mommy’s gonna make sure you survive.

— Amber Smithers

Since then, she has submitted poems on a variety of topics. Fellow poet Rita Marie Recine remarked that she could truly relate to Amber’s “I use to want to be a siren…”:

I use to want to be a siren.

Bringing men to their knees.

I wanted to be Mother Nature,

Giving men a high they could not deny.

I thought I could be Eve.

Made by Adam’s rib,

Making him do anything I willed.

Now I wish to be me.

Not just a complex,

Trying to find adoration in his eyes.

But a woman with a mind.

—Amber Smithers

Amber continues to grow as a poet. Among her most recent poems at The Song Is… was a very personal piece about bulimia. She is also beginning to submit to other magazines, a necessary next step in her development as a poet, even if she meets with occasional rejection.

Alex has also contributed to the blog-zine, reviewing Valeri Beers’ chapbook details… and submitting much striking poetry. His first entry brought together several of his best poems from our poetry class: “Self-Portraiture as a Rain-Soaked Weeping Willow” and the bilingual “Within the Darkness of Dusk” especially impressed me both in class and at the blog-zine. In his most recent entry, Alex augmented his wise, searching poetry with arresting images. It is true that his is a very visual generation, but his approach fits in well with The Song Is….

Blogspot allows me to include not only links to music but also images. Several entries have been more visual than verbal. The collaboration by former student Jerry A. Scuderi and photographer Juan Tituana comes to mind here. A mature student, Jerry himself displays a distinct style in his poetry. (Jerry, by the way, is also a winemaker.)

My blog-zine has become a teaching tool, not only for my former students but also for novice writers. Recently, poet and educator Avis D. Matthews sent me some powerful poems by a former student of hers, which I will be publishing later in September. I also published the poetry of Gabriel Eziorobo, a high school student from Nigeria. Initially, at times, I had thought of my blog-zine as being separate from my work as an educator, but now I have come to view it as very much a part of my profession. Sometimes I have been disappointed that promising students did not submit work. Over time I have realized that my “students” online and at the blog-zine will be different from my students offline and in the classroom, but education is not limited to a select group. It must be available widely.

Images by Juan Tituana

The poems below are my teaching poems. The first, “The Poet Charlotte Drives Away,” imagines the British author Charlotte Turner Smith (1749-1806) as a 21st-century adjunct instructor, writer, and single parent in the Washington, DC area. One could also say that this poem is a tip of the hat to my life as a student of 18th and 19th-century British literature, a time that seems very far away now. The second, “When Addison Road Was the End of the Line,” reflects on my own days as an adjunct instructor, a “subway flyer” teaching at various colleges, including Prince George’s Community College, a bus ride away from the Addison Road Metro. The last, “Writing with an Empty Mind,” was inspired by reading an anthology of poems by LGBTQ teachers, This Assignment is So Gay, ed. Megan Wolpert, in particular Nathan Daniel Terry’s “A Student Says She Hates Nature Poetry.” Terry showed such grace in responding to his student that I wanted to emulate it.

The Poet Charlotte Drives Away

Her brain buzzing with botany,

backpack crammed with ungraded papers,

Charlotte wants to create a found poem,

transmuting the latest scientific research

from Memoirs of the New York Botanical Gardens

into poetry about lichen and peat mosses.

She crosses the quad,

contemplating the students

amongst the bricks and roses.

A girl in a sari tries

to sell her a samosa.

A grad student in a burkha

retreats to the library.

Charlotte holds her head high

and buys nothing.

She wants to write free verse

arguing against hiding

in cloth & custom

from the sunlit life.

There will be neither

lichen nor roses

nor research

in this poem.

Unburdened

by sari or burkha or skirt,

Charlotte in capri pants

hops into the driver’s seat

and peels herself away.

She imagines writing

a poem for children

from the perspective

of a girl in a hijab.

A driver in a wig and micro mini

honks at her for traveling too slowly,

too thoughtfully on the highway.

Charlotte puts her sandaled foot down

and rockets towards home.

Somewhere further along,

past the clot of malls,

she merges into traffic,

and her mind returns to a sonnet

about a man shouting

at waves crashing

on an empty English shore.

She will write this one down

in her house like a beekeeper’s hive,

one of many in a row

on the site of a fallow farm.

Her children will buzz around her

as bill collectors call.

When Addison Road Was the End of the Line

Beyond there were only buses

the C29 down the highway

past strip malls, past farm stands,

past the DMV and the gas station,

to the front door of the college.

Then she was a moon-faced girl

in black among the masked faces,

the stout security guards,

and the boys to men

with blank white shirts

and shorts past their knees.

That was nearly ten years ago.

She looks like her mother now,

tightening a gunmetal belt

over a navy cardigan.

She walks to work.

Someday she might come back

to see what Addison Road has become:

the new town center, the stores,

the station

a village green with

Kenny the mayor on Foursquare;

it’s no longer the end of the line.

Writing with an Empty Mind

Writing with an empty mind,

I wonder what words will come up

to fill this emptier page.

Reading, I find

phrases to build on

in the new fashion. Poets to quote.

I stop at one poem

to a student in Carolina

who would rather write about the body

than about nature.

I am reminded

Of my students who are tired

of trees in poems

Of others who argue

against birds

when we talk about wind farms

Of myself once

pretending that the wood

behind the house was a city

and then walking every inch of it.

A collaboration with Marianne Szlyk and Angelee Deodhar

An eye surgeon by profession, Dr. Angelee Deodhar, is a haiku poet, translator, and artist. Her haiku, haibun, short stories and haiga have been published internationally in various books and journals, and her work can be viewed online too. To promote haiku in India, she has translated six books of haiku from English to Hindi, the other official language of India. She has edited both Journeys and Journeys 2015: an Anthology of International Haibun (available on Amazon), which has a total of 145 haibu by 31 poets of international repute. She lives and works in Chandigarh, India.

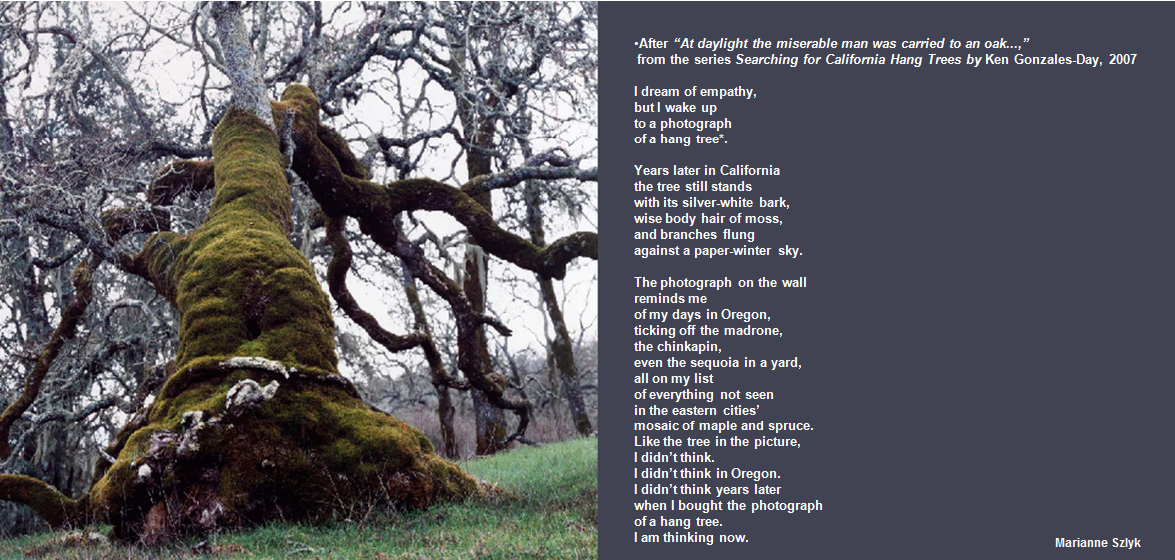

Writing about the Environment

I struggle to write political poetry—except when it comes to the environment. The environment is an important cause for me and my husband. As I mentioned in my first post at The Wild Word, neither of us drive. He bikes, and I walk. We both feel anxiety over climate change and the degradation of our planet. In particular, I worry about growing old in this environment of erratic weather, poor air quality, and shortages of potable water alongside the ocean’s floods. Not yet old, I imagine summer as a season of cabin fever.

Place is also important to me. I grew up in New England, a part of the country with a strong regional identity that was even more dominant during my childhood in the late 1960s and early to mid 1970s. As a child, I spent much time with my grandmother, who did not drive, and so walked everywhere in her small, run-down city of Fitchburg, Massachusetts. Since my mother did not fly and my father did not like to leave his dental practice on extended vacations, we traveled within our region or up to Eastern Canada. I ended up going to school near Boston where my classmates from New York ridiculed my then-strong regional accent, and I spent too much time wandering around aimlessly with a man I eventually married and then divorced. I finally left home for graduate school in Oregon, another part of the country with strong regional pride. Indiana, the state where I completed my graduate studies, has a similar pride. I still remember how much students enjoyed writing about growing up in small towns, farming, hunting, and being part of 4-H, an international agricultural organization that encourages young people to learn by doing, in their environmental autobiographies. For these reasons, it’s not surprising that I gravitated toward environmental poetry.

The poems that I’ve collected here are just a sample of my poems on the environment. Moved by the ongoing drought in California (where my then husband and I had once considered living) and an obsession with Detroit’s ruins, I wrote ‘We Disaster Tourists Travel to the Salton Sea.’ Each stanza of this poem, by the way, is in haiku format. Recently I was shocked to learn that Massachusetts, my home state, was experiencing drought as well. ‘The Drought Closer to Home’ was my response. It especially pleased me that Russell Streur chose this poem for his Plum Tree Tavern, a blog-zine for poems of environment advocacy. One impact of climate change is the migration of plant and animal species from one zone to the next. ‘Crape Myrtle’ depicts this. (The poem appeared in the Taj Mahal Review as ‘Crape Myrtle in East Rockville,’ that is, in my current neighborhood.) Flooding is yet another impact, which I portray in two poems, ‘She Wonders What Will Become of Everything’, where the speaker contemplates the future, and ‘Easter 2116’, where the speaker inhabits a time of holograms, flooding, and mosquito-borne illness. I conclude with ‘At Low Tide’. Although it is not a political poem, it evokes the beach, specifically York Beach, Maine, which is not just high tide and sunshine but also low tide and fog. If we are to cherish the environment, we must recognize its diversity as well as its value in itself.

We Disaster Tourists Travel to the Salton Sea

Last year’s flowers stand,

sun-bleached kindling for the fire

about to happen here.

Blue sky flames, a torch

in the earth’s hands. The sun is

the white-hot center.

No one smokes. Engines

do not idle. Air effaces

smells of death and life.

All that remains in

the sea’s heart will never quench

the flames we wait for.

We wait, take small sips

of bottled water, then wait

some more. We tourists

Fly from disaster

to disaster, our quick flights

adding fuel to the flames.

The Drought Close to Home

So close to the sea, the Scituate reservoir

contracts to shards of clouds and sky.

Smashed on thick mud, these shards

shrink from the tree trunks and stones

rising where water once flowed.

Humid air promises rain but does not

release it. Blue sky persists

though towering clouds form.

No storms arise,

even rumors of thunder

off the coast.

Afternoon sun

grinds the shards to dust.

She Wonders What Will Become Of This City

The sky above swells into a bruise over a blood vessel.

Swarms of mosquitoes rise from puddles and gutters.

It is always about to rain, sometimes about to thunder.

Acid rain cannot cleanse the ground or the air.

The pages of books dampen and thicken,

becoming too heavy to turn, too blurred to read.

The green fuzz of moss grows over trees

like plaque on teeth. Bones ache with decay.

Buses stall. Last year today would have been Code Red.

No one walks. No one rides for free.

She wonders what will become of this city

once the oceans rise and ghost towns form like coral reefs.

The real coral reefs will have crumbled,

all color leaching away into the corrosive sea.

She wonders if the people huddling miles inland

will ever visit the abrasive waters

and imagine what might have been

in the ghost town where she now sits.

Or will they avoid the scouring waves

and build their lives on mountains, now islands

above the waters, above the swarms of mosquitoes,

above the trash of daily life in a ghost town?

Easter 2116

Among the late-afternoon walkers in the square,

I tighten the hood around my pale face

and squint through goggles for

any scrap of sun that squeezes through.

I could be on Bradbury’s Venus on the sweltering day

when the sizzling rain pauses, but I am on Eaarth.

In the absence of wind, showers, and past birdsong, I hear

my robe swishing. I will myself

not to think about music, my own earworms,

or suggestions sent to me like headaches.

I hear only the buzz of mosquitoes, balked by the heavy cloth.

Shuffling, weighed down, I watch holograms hover

over the soft stones of the square that resist ceaseless rain and wind.

The holograms show skin, unlike the living.

Mosquitoes will not bite them. They have no blood to poison.

Holograms do not talk to me. I am too poor and homely.

They are as silent as the electric cars and aircraft

that swarm the city and beyond.

I walk to the shore of the acid ocean, the beach

lacquered with toxic jellyfish and seaweed.

I smell nothing. I have been walking

here forever in search of something.

A hologram in cargo shorts floats above

like a new-age Jesus going out to Peter’s boat.

I look out to the horizon. The waters cover the cities

where, as children, the holograms wore Easter outfits

and couples sauntered out in the sweetly-scented sun

so many years ago as music played from transistor radios.

The rain will resume. The music will as well.

For now, I enjoy their absence.

Crape Myrtle in East Rockville

In each yard, lavender, white, and scarlet

spring up like bouquets in children’s drawings.

These trees never grew this far north before. Yet now

they color my neighborhood when roses and lilies wilt.

Someday kudzu will compete with ivy for my neighbors’ fences,

for the yards of abandoned houses, for the trunks of trees.

In all seasons, palmetto palms will flourish. Away from acidic winds,

Spanish moss will hang from branches.

The people still living here will keep banana trees

on their porches. Brave neighbors will pick

the finger-sized fruit for breakfast, a curiosity

like this crape myrtle once was.

At Low Tide

Already a ghost at twenty-three,

the singer Tim Buckley howls,

scaling octaves, stretching out syllables

until they dissolve in salty mist.

His fog of consonants and vowels,

salt and smoke, hovers, grazing

the skin of the dark-haired woman

standing by the window, holding

a candle in a baby-food jar.

Outside stairs to the second floor

quiver beneath keyboards and bass,

heavy footsteps of a ghost.

She turns away from the sea.

Cupping her hand around the

white flame, she blows out

her candle before the voice

breaks the last barrier

between indoors and out. Nobody

walks out on damp sands,

so far from cold water,

much further from yesterday’s warmth.

Nobody walks out at low tide.

Even the seagulls dissolve

as if they were salt.

The woman at the window

has turned away. Her man

will not climb up to her,

not this morning, not tonight,

not when the fog wails

and salt embitters the air.