ARTIST-IN-RESIDENCE

★ ★ ★ ★

CHARLOTTE BRISLAND

We love artists at The Wild Word.

Our Artist-in-Residence page provides a space for artists to showcase their work and to spread their creative wings. In their month of residency, invited artists are encouraged to collaborate with other contributors within the magazine, to experiment and develop new projects, while giving us an insight into their creative process.

Our DREAMS issue Artist-in-Residence is Charlotte Brisland.

‘A Day in the Life’

6.30am – Wake up call

Get up before the kids get in trouble, make breakfast, eat breakfast. This morning its BBQ crocodile as we’ve chosen to live temporarily in Florida.

8.45am – Mad panic, scramble up the street to school, through the school gates, bell

8.50am – silence

8.55am – running, thinking, sea.

The sea and my feet fall in and out of synch. I watch as the waves move, lap, rise, fall, breath, deep green this morning, one of the most expensive colours on the spectrum next to pure pigment lapis lazuli; cobalt turquoise. The sand and pebbles have gone orange, a deep yellow, cadmium. The sky teases blue behind heavy grey cloud. It might rain.

11am – The studio is tidy so I quickly pull out all my images, pens, books, paint, brushes and think. Today there are no blank canvases or large works underway. I’m working on smaller pieces on card.

The lines begin, entwining forming, growing, spreading through the white page and become….uncertainty, abstraction, contemporary, a figure, a tree, a rock, shade, there’s some renaissance in the sky.

And then it speaks.

‘Let’s do something different today, I’m tired of the same old same old, let’s branch out!’

‘What? Where’s this all coming from? What about that eclectic thing we discussed?’ I ask, ‘Couldn’t you just be a bit more visceral, cut and paste from moments in Art history?’

‘Not today. Today I’m thinking about fairy tales, why not do one of a hedgehog, kittens maybe?’

‘That wouldn’t be very good, too reactionary. We have to stick to the program, be consistent. Anyway, why kitsch all of a sudden, we aren’t thinking of adorning chocolate boxes suddenly?’

‘I don’t want to be monochrome anymore’, the painting huffs stubbornly.

‘Well, see, that’s just irrational.’

Silence.

‘Ok, look, how about for today we use a bit of colour? It might be alright if its small scale’ I coax.

Smiles.

‘I’ve only got pens in colour, so what shall we do about that? It won’t even be a painting. I’m a little concerned about change,’ I say.

‘You know, just begin and see what happens, you’re an artist, and it will just grow.’

‘Thanks,’ eyebrow raised, cynical, wondering where all this is going.

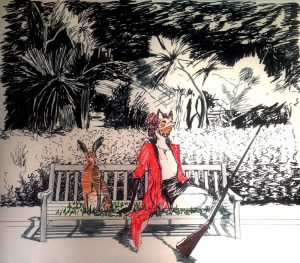

So I begin with a thick black pen, and some narrative grows into it. I finish.

‘This looks like an illustration’ I observe.

‘It’s still monochrome,’ grumps the picture.

‘Don’t worry, I’ll add some colour…there, some red, green, yellow…ok?’

3pm – collect children, playground screams, happiness, school bags.

Let’s go to the park, it didn’t rain after all.

Chats with other parents, a jewellery maker, an illustrator, an actor. All taking a break with small children, we’ll get back into it soon.

4.30pm – get in from the playground and start dinner. The children draw, I join them briefly between pots and pans. Sophia lends me some new pens of hers for more colour variety; I think the picture will be pleased.

7pm – book and bed, gentle snores follow.

8pm – tired.

Look through some Art magazines and apply for a few competitions, exhibitions. Watch a little TV.

10pm – sleep.

STRANGE AND FORGOTTEN CORNERS

★ ★ ★ ★

‘Block’

‘Corner’

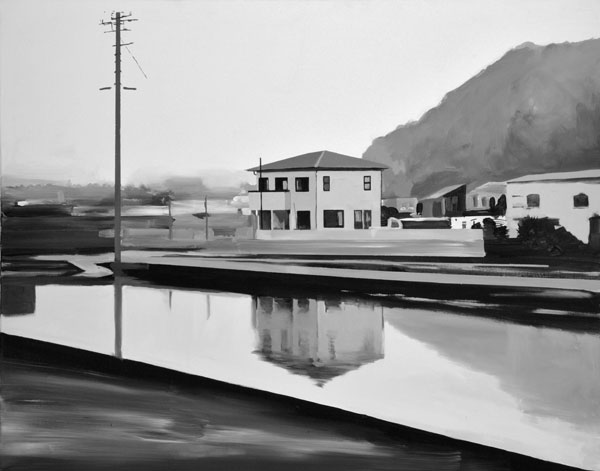

The paintings I make are always of the landscape, placid and distant. The brushstrokes are sometimes broad and visceral balancing precariously into photorealism. What is depicted figuratively within the composition is often a single building or piece of street furniture. Why are we looking at this house or this building or this tree? There is never a real response to that, nor do I want there to be. There is a building, that is all. But there is more, there is the sense from the viewer, their own ideas, the possible ideas of the artist and how it is positioned in contemporary dialogue.

The work has always been inspired from seeking new landscapes, placing myself in unknown environments, cultures and countries such as Japan, France, Berlin and Switzerland. It was never enough to simply visit these places, I lived and worked and engaged fully within all of these places. Only through that whole experience did I begin to see the strange and forgotten corners and spaces. Overlooked and secondary those spaces became important to me for that very reason.

As featured in the international, independent art magazine – FreshPaintMagazine

‘Block’ and other works are available as prints. Each print is £40. Limited edition run of 75, all signed.

For further enquiries contact the artist directly at charlotte.brisland@outlook.com

CONVERSATION WITH A PAINTING

★ ★ ★ ★

‘Conversation with a Painting’

By Charlotte Brisland

In my opinion, the most fascinating thing about the creative process is the conversation between the work and the maker. Yes, the work talks back, when the process is really, really working. There is a relationship between the work and the artist that exists across all fields, between the instrument and the musician, the sculpture and the sculptor, the text and the author. The conversation is silent or musical, there is intuition and spirituality.

I have an artist friend who recently described her paintings as sometimes behaving badly, “like bad lovers they finish way before me”.

A stream of artists commented in whole-hearted agreement,

“Absolutely! Couldn’t agree more! Hit the nail on the head, couldn’t have said it better myself”.

My own comments were there too – “Wow! That’s exactly it”.

There are moments where everything falls into place and it is just ‘finished’, the process is over, the last page of the book has been read. Occasionally I’m relieved when a particularly long and difficult painting is finished. There are others I’ve simply had to walk away from when the composition or the paint were too problematic. Then there are the ones to be secretly proud of, when I quietly muttered ‘yeah, that didn’t go too badly’ (warm inner smiles). Those are the ones that end well, mutually agreed, never to be forgotten. They aren’t always the collector’s favourites either and that makes my relationship with them ever more intimate.

The process is the most sacred part, building the stretcher, stretching the canvas so that it isn’t too taut or too billowy. There is a sound the canvas makes when it has been perfectly stretched, flick it and it will make a deep reverberating dooong, like a drum. Then goes on the primer, which has to be mixed to the consistency of double cream. Pull the mixing brush out of the jar and there should be no break as the liquid flows downwards. The first layer of the primer needs no less than 24 hours drying time before the next layer, the subsequent layers need only 2 hours. There must be at least 5 layers of primer for a good surface, do not attempt painting for 24 hours after the last layer has been applied. Preparation time for each canvas is at least 3 days. More days and more layers equal a zingier painting. Each layer means more pigment remains on the surface, so more colour is visible.

If the building of a canvas is all care and patience the painting is an experience unique to each individual artist. For me it begins in an aeroplane, let’s say mine is red, perfectly compact, vintage, quirky. The painting will only really ‘work’ if this aeroplane, who I will call Lily, can find the time and energy to get up the speed she needs to take off. There must be a clear space, time and concentration, any distractions in that phase will mean Lily either can’t take off or she crashes, both are extremely frustrating. Once she’s in the air there is some freedom to kick back and play in the air, letting the paint brush glide across the beautifully prepared canvas, creating abstract forms before getting bound into line and direction.

The doubt is the worst. Sometimes the painting will take up the role of the gentle lover and assure me there is beauty, it is worthwhile, there is a place for it in the world. Sometimes there is only abandonment, failure, loss. But that’s all part of it. The doubt is beautiful too. It’s just the other side of the process.

When a painting looks to me as though it might end I sometimes cheat and walk away for a while, just to prolong the process and my relationship with it. Once the work is finished it belongs to the world, it needs a home. It needs to be admired and loved, cherished and cared for. The process of making the work is what keeps me doing it, time after time. Each canvas takes up the conversation from the last one, and so it goes on and on for years and decades and a whole lifetime.

‘The Edge of the Sea’

★ ★ ★ ★

‘THE STUDIO’

My studio is in my home and is in a constant state of change. It’s the place where my children play, toys get muddled with paint pots, ideas get discussed, friends come for dinner at my desk/dinner table next to the work and then I paint sometimes too. It isn’t an isolated room for quiet thinking, it has a buzz of life at all times and I love it.

Time changed for me once the children were born. It feels important to be quite fluid and compromising as I might have to put down tools in the middle of an important moment for the school run, sudden illness or doctor’s appointment. It’s changed me a lot, which I like. There’s not much room to dawdle or drink a bottomless cup of coffee for hours. I’ve got to be more disciplined but also more relaxed about things, which has given my work more energy and less neurosis.

Before I had my children, when I was studying at the RCA the message was clear, DO NOT have children if you want a career as an artist, ESPECIALLY if you are female. So when I made the decision to have a baby I put away my brushes and canvases and believed that would be the end. I was fully prepared to make the trade that I thought was inevitable because I really wanted my children. As the months past and my belly grew around my baby I got fractious and decided to make just one more painting. For some reason it was the most focused and energetic painting I’d done. Having children was definitely not stopping me as an artist, it was propelling me. Protecting and thinking about someone else for most of the time took away a lot of cluttered thinking and made me stronger as a person and an artist.

A COLLABORATION BETWEEN MOTHER AND DAUGHTER

The World is a Special Place

★ ★ ★ ★

The World is a Special Place

A place to be

a feeling inside

a heart full of things,

a wonderful place to be

A little loving song that makes you happy

whatever comes

in your way, love them

What a place to be

we all have a special place to be

inside

Written by Sophia Manss (age 7)

‘The psychological landscape’

By Charlotte Brisland

The invisible barrier between the conscious and subconscious, between real landscape and dreamscape, is anchored in a single certainty of the self. The idea of the ‘self’ is so ingrained in the physical that it can’t and shouldn’t be ignored — it is pivotal. How I see is also how I perceive. Sometimes perception can begin to shift so that what was once familiar becomes unfamiliar.

My own experience of this shifting balance, which manifested as anxiety, began as a teenager. Going home began to get difficult when I was around fourteen. Meandering around blocks, walking back as slowly as possible and then feeling the fear and trepidation five or six doors away became a daily experience. The house I’d grown up in took on a silence and a weight that was never there before, but it was coming from me. I hid in my room and sank into the dreamscape of my paintings. They helped me to focus on something other than the present; I could think and control my own world. I would do that for around five hours every evening between getting home from school and going to bed.

As soon as I was old enough, I began to travel, first through Europe and then Japan. I didn’t know it at the time but I was running into landscapes that had nothing to do with me perhaps in an attempt to counterbalance my own sense of malaise. A feeling of ‘uncertainty’ is something everyone will experience when they move to a new culture. At least that sense of ‘uncertainty’ was real to me, and somehow exciting. The landscape looks similar—a cup is a cup everywhere, a table still stands on four legs, food is wrapped in a plastic film—but the packaging is different, the words on the package are unfamiliar, something has shifted. At first that’s exciting, but over time that becomes something else. Frustration overrides, the individual slips into what is known as “the uncanny valley,” and they can feel lost and isolated. When my experience of feeling lost and isolated got too much I moved to another country until I began to feel weary all over. When I arrived in Berlin I had already “lived” in three countries; not including the UK where I grew up. I made the conscious decision to stop running and decided to make it my home. After Japan, Berlin did feel more familiar to my European western upbringing. I met a boy, thought I was in love, and started a family.

During the pregnancy my husband drank alone, which he had done before. It was upsetting to me, but it didn’t seem to be such a big problem that I was willing to sacrifice my relationship. We had a little girl. It was the happiest day of my life when she was given to me, a perfect bundle of baby, all purity and life and love.

In that moment I changed completely; I was no longer a child running through life in a dream. I had to be a fully functioning grown woman. I promised her I would keep her safe and perfect forever. In that moment my husband seemed to disappear from view. He became more and more distant, hiding under the banner of a “mother’s instinct”, or “I’m too tired”.

I thought he just needed time, but as our second baby was born he was hiding bottles of liqueur around the house and using bottles of mouthwash as a way of hiding the smell of alcohol in his breath. He slunk away from doing anything in the house and the verbal abuse crept in. I began to take anti-depressants and slipped into a numb dream state.

I told myself it would pass and that he would go back to being the loving husband I had married. But he didn’t. He just stopped hiding everything else, denying anything was wrong or that he had done anything to hurt me. I drifted into a state of almost total invalidation until it came to my children. I knew they needed me.

I finally got up the courage to move back to the UK without my husband. My family were not supportive. They dismissed me entirely, saying I had post-natal depression and had made everything up. They wanted me to go back to Berlin and stay with my husband. I spent some time without a home and in a hand to mouth existence. But I knew it was heaven compared to where I had come from, I also had the unwavering belief it would get better. The worry that I might not be able to feed my children was constant, I don’t think that has really ever left me.

I still haven’t been back to Berlin because even to remember it can send me spiralling back. It isn’t Berlin that is the trauma, the trauma is in me. My perception of Berlin is a landscape shrouded with negative memories.

The landscapes I have been painting since I was twenty-one were always about my anxiety, but it has only been in the last two or three months that I really understood why. The paintings turned monochrome just over a year ago when the trauma of these events began to take hold. I always rationalised the decisions in my work through academia, and I will continue to validate them that way, but they come from the deepest part of me and that will always be two steps ahead of my conscious self.

Painting: Block. Acrylic on Canvas. 2015. 100x120cm. Charlotte Brisland

Private collection, Dominic Fitzgerald.

At the age of 7 Charlotte Brisland wrote a letter to Father Christmas asking that instead of presents that year she would prefer “to become a famous art worker”. As an adult; age 12, Brisland made the decision to begin her career as an artist and began painting in all her free time. Her first-ever exhibition was at the public library in Portsmouth when she was 17. When she realised the landscape was possibly the most profound thing she could work with, Brisland decided to take long vacations to foreign countries as a way of truly experiencing them inside out. Sometimes the long holidays became independent residencies between 1 and 5 years. During that time, Brisland’s late Christmas present arrived in the form of an acceptance letter to the Royal College of Art in London. After that, Charlotte Brisland began to exhibit all over the world in Europe, Japan and New York. Recently, as a very old lady of 37, Brisland has settled right back where she began in the seaside town of Portsmouth with her two children. She is very happy.

Fabien Leseure is a French composer and musician. He lives with his family in Berlin.

For information on his music you can visit his SoundCloud page.