THE NARROW FELLOW

★ ★ ★ ★

FICTION

Story by Erin O’Loughlin

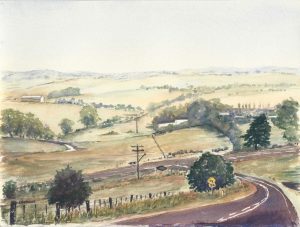

Watercolours by Lorraine McDermott

Driving out to the farm could take two hours or a hundred years. Once you turned off the highway, little pockets of loose time littered the road. Bermuda triangles that had captured primary school friends back in the eighties and swallowed Main Road bakeries and grocery stores whole now regurgitated them into the path of oncoming cars. Ghosts of friendships past slithered in through the windows and pooled in the back seat. By the time my wheels were spitting up dust and gravel on the dirt road, twenty years had come and gone inside my Toyota. As I reached the end of the driveway, I saw a knotted huddle of calves crowding the top paddock. Somehow they had escaped the butcher’s knife and been deposited back here, with their fuzzy heads that used to butt up against me trustingly, the hoofs that trampled my boots in their baby bovine excitement. God, the innocent sweetness of their long bluish tongues licking milk off your fingers, and the enthusiastic way they sucked at the rubber teats Dad had fixed onto the old yellow bucket! I looked for the one with the white flash on his forehead, but these were reincarnations, not carbon copies. Still, they had the same big brown eyes that waited patiently for someone to come fill their bucket, maybe scratch their heads the way Jen and I used to do. No one came out of the house though, not even in answer to the sound of my car pulling up. I got out and slammed the door a little loudly on purpose, hoping Mum would hear it, then felt childish. Coming home always brought out the teenager in me.

Myxie was waiting for me on the veranda steps, and I leaned down to scratch her head while she rubbed against my legs. Mum liked to say Myxie was as ‘white as country music’, but white was the wrong colour for an outdoor cat—in summer I had to hold her down each morning while Jen put sunscreen on her pale pink ears and nose to stop them burning black. But in all other ways she was a country cat—that blend of house-proud hearth kitty and stone-cold killer. She’d attack anything smaller than a poddy calf, if it made the mistake of coming onto her farm. Rabbits were her speciality, little limp, bloody bundles of fur that she left outside the back door for us to find in the morning. We called her Myxie as a joke, after myxomatosis, the virus that scientists released back in the fifties to decimate the rabbit population. They say that within weeks the dusty fields were full of twitching, brown bodies, riddled with tumours. Ninety percent of the rabbit population was gone just like that, goodbye Bright Eyes and Thumper. But science had forgotten that rabbits, even just ten percent of them, go at it like rabbits. Before long, there were plenty of children filling up the empty burrows. Myxie stalks the descendants of the survivors now, the ones that developed immunity and bred their resistance into the next generations. What doesn’t kill us makes those who come after us stronger.

The back door was unlocked, and Mum was asleep inside on the sofa, grey hair falling across the cushions. Putting my bags down quietly, I picked up the blanket that lay over the armrest and spread it over her. I was trying to be gentle, but she woke up anyway, and immediately started to fuss.

‘Nina, when did you arrive? I must have fallen asleep!’

‘Just right now Mum, don’t worry.’ Adolescent impatience in my every syllable. ‘I just came in, literally this minute. Relax.’

‘No, no. I’ll make you a cup of coffee. Or tea? Are you drinking caffeine?’ Her eyes strayed to my belly and then back up again.

‘Just relax Mum. I tell you what, you make us some tea, and I’ll go out and feed the calves. I saw them all up at the top of the field.’

Her shoulders slumped, and I saw a look of relief pass across her face.

‘Would you, love? That’d be great. I’ll get dinner started. Dad’s old gumboots are by the back door.’

Dad’s boots were such a back-door fixture that I hadn’t even noticed them on the way in. They sat there strangely vacant, empty in a way they’d never been empty before. They’d always sat there, in various states of muddy, except for the time I’d lost one. I used to take his boots to walk in the long grass in the back paddock, although it made him furious to find them missing when he wanted them, and I hated to make him furious. But they felt safer than mine, coming all the way up to my knees like armour. I was a knight, off to my own kingdom, down where the river red gums screened me from view of the house, and the steep erosion formed a personal canyon. I wasn’t supposed to go back there alone. The creek was unsupervised water, its depths dark and alluring on hot days. One time Jen swore she’d seen a platypus near the bend, where the water swirled deepest.

I was running to the creek the day I lost his boot. Racing for the fun of it through the long yellow grass that slapped around me, dry and scratchy with the end of the summer. Dad was meant to have cut it into bales already, but he was late that year, and the grass seemed to tower over my head. One moment, it was just me, alone in an endless wave of late afternoon gold, and the next moment, I was rising in the air, my body somehow leaping over a huge brown snake my brain hadn’t registered yet, long and hefty, lying in the middle of a swathe of flattened grass. We’d been learning Emily Dickinson at school. A narrow fellow in the grass. His notice sudden is.

Country kids are always taught to stand still if you see a snake. But you never really react the way you’re supposed to. You don’t walk calmly to nearest exit, you never tell your teachers what he did to you, you don’t remember how many compressions and breaths per minute, or hurry during a fire drill. I was jumping before I even knew I’d seen it, and from mid-air I watched in horror as the gumboot slipped off my foot, on a perfect trajectory for that bronzed designer-handbag skin. I was on the ground and several meters away before it hit, and the whiplash body coiled up and struck the boot several times. I ran all the way to the fence without stopping, then clung onto it, my heart beating hard and my mouth dry.

Such a long walk back to the house. The afternoon light slid away from me before I was halfway there. Each step with my one bare foot was terrifying. The tremors of the grass sent shudders through me. I could see the lights coming on at home, and hear the sound of the calves being called, and I knew Dad would have noticed the missing boots.

He was waiting for me by the chook shed, his furious aura making the chickens cluck nervously. His scowl grew darker when he saw my one boot on, one boot off, and I knew I was in for it. He threatened to send me out there barefoot, but even with his big fists right there in front of me, I wouldn’t go back. I could see those fangs sinking into the boot, even though I had been running in the opposite direction. He stared at me coldly, then grabbed a shovel that was leaning against the shed and stalked off into the paddock. I was in my room when he came back, lying low, and he came and stood at the door, the boot in one hand. I thought he might throw it at me. Instead, he raised the other hand and showed me that thick, brown body, dangling from his grip like a rope. I felt sick.

‘Biggun,’ he grunted. ‘You were bloody lucky.’ And he left.

He hung the snake from the back fence for a while, until something made off with it one night. I remembering wondering what ate snakes, and whether they got poisoned by the venom.

Now, I tapped the boots against the veranda, and turned them upside down and shook them. Then, because city living was really making me soft, I pushed down on the toes as an added precaution, squashing them flat a few times before slipping my feet in. It felt cheeky to wear them, like I was playing at being Dad, feeding the cows. Later that evening, I had the same feeling as I sat in his big, green armchair, while Mum made me a cup of herbal tea.

We sat in silence, real silence, the kind that comes with darkness on a farm, and listened to the fire pop and hiss.

‘I should work on my thesis.’

‘There’s plenty of time for that.’ Mum looked at my stomach again, the barely-there bulge. ‘Have you thought about names yet?’

‘There’s plenty of time for that.’ We both laughed. ‘Am I sleeping in my old room?’

‘No, I’ve put you in Jen’s old room. The bed’s bigger.’

‘I can’t believe you just said that.’ My amazement was genuine. ‘ My entire adolescence you denied Jen’s bed was bigger. It’s like…’ I searched for an appropriate comparison. ‘It’s like if you told me you never really liked my mother’s day gifts in kindergarten!’ She laughed at that.

‘ I kept those things for years! I loved those.’

‘ Exactly. Or like if you said you don’t go to church anymore, after making me go every Sunday my whole life!’

Something in the play of firelight on her face gave her away, eyes dropping to the floor sheepishly, like a child in trouble. I gaped at her.

‘You can’t be serious. You don’t go to church anymore?’

‘Oh well, love, you know. Once you kids finished school, we didn’t seem to know anyone anymore. There didn’t seem to be much point.’

I stood up. ‘I’m going to bed.’

* * * *

In the following days, time was fluid, non-linear. Each day I would retrace some childhood ritual—the steady stirring of viscous honey into camomile tea, cutting French toast into precise regimented soldiers—feeling echoes of my childhood self one moment, catapulted forward into a parent’s role the next. Mum was the one curled on the sofa under a blanket, who needed a cool hand on her forehead, a caring smile, and someone to seamlessly take care of things while she listened to gardening shows on the radio or read Georgette Heyer novels.

‘You’re not going to turn into your mother,’ was the last thing David had said to me, as he loaded my suitcase into the car. He was so literal-minded sometimes, misunderstanding my little joke as I mimicked her pre-road trip ritual, flicking the sun-flap down before I got in the car, in case there were any huntsman spiders lurking on it.

‘No, I…’ I realised I didn’t have the energy to explain, and just kissed him goodbye instead. But we were both wrong anyway. My mother, or hers, or anyone’s, it didn’t matter. We all shared the same cycles of worry, the digging for unknown strength, the mundane daily love. I’d always had a child’s desire to protect my mother, curled up inside the desire to protect myself. I could hear Jen whispering in my ear, ‘She made her choices Nina. We have to live our lives.’ I wished so much that Jen was here. We could giggle together late at night about old classmates grown fat, who’d married who, and who had never left. But Jen was living her life as far away as possible.

‘I need to get some work done on my thesis,’ I told Mum on the fourth day.

‘Go on then, love. That’ll wait.’ She gestured at the washing I was folding up, but she didn’t get up to help. Myxie leapt up onto the chair I was placing everything on, batted a pair of socks onto the floor, and started to chase it around. I kept folding, while an old lady with a quavering voice called in to the gardening show to ask whether she really needed to cut her roses back very hard this year. ‘Listen Beryl,’ the host replied bombastically, ‘You can’t let it slide for a single year. You have to cut off all those old, weakened branches, so that you get new strong ones growing through. You let all the light and air get into the plant, and that’ll help to protect it against fungal diseases and the like.’

Dad had taught me that, outside in our scarves at the end of winter, me as high as his armpit, staying close to his comfy bulk.

‘You have to cut it right back, or you won’t get any new growth.’ Our heads bent together as he showed me the new buds on the branches, and how to trim on an angle just above them. He handed me the secateurs, and held the branch to show where I should cut. Too big in my little, inexpert hands. The edge of the blade caught his finger, and bit deep into his flesh.

‘Fuck!’ The secateurs went spinning away. Blood speckled the leaves. His face was a red rush of anger, his whole body suddenly hard and mean. ‘You stupid little-!’ He slammed into the house.

An hour later, when mum had bandaged him up and calmed him down, I showed him the rose bush I’d pruned all on my own.

‘I cut off all the dead wood, Dad.’

‘They’ll look stellar this year Nina,’ he told me, resting his bandaged hand on my shoulder. The roses were covered in aphids that year, as it turned out, but we agreed that the bushes had a beautiful shape.

‘Mum, why do you listen to this? It’s not like you do any gardening.’ I leaned down and tried to rescue the socks from an upside-down Myxie. She sank her claws into them and tugged them back to her chest.

I drove to the shops, I scrubbed the bathroom grout with an old toothbrush, I mowed the lawn around the house and weeded the garden beds. Finally, I got out the box of sympathy cards that had been sitting on top of the dresser.

‘Are we supposed to answer these?’ I asked Mum. ‘Do you send thank-you notes for sympathy cards?’

‘Of course you do.’

‘Seems a bit unfair,’ I shrugged. ‘I mean, you’re the one…’ Her look stopped me. ‘Where are the envelopes?’

She came over to the table with them, and sat down beside me.

‘I didn’t want to answer them.’ She said in a low voice. ‘There’s people in there who never gave a damn about him while he was alive. His brother.’ She shook her head agitatedly. ‘Why should I accept their sympathies?’

‘You don’t have to,’ I said. ‘I won’t write to him. I’ll just do the others.’

‘Oh, they’re all as bad as each other!’ She exclaimed. ‘And he was no better than the rest of them.’

‘So do I write them, or not?’

‘Of course.’ She said. ‘I’ll make you a cuppa.’

Time was a river of endless cups of tea, punctuated by the mundane chores of death. I drove dad’s clothes down to the Salvo’s, but I left his gumboots sitting by the back door. I felt somehow soothed by their presence, but they stirred some germ of latent independence in Mum.

‘We should get rid of them.’ She put her book down and got off the couch. ‘I should get rid of the whole damn lot of it.’

‘You don’t have to.’ The sudden cleansing rush of energy was shocking, unseemly. ‘We could do something decorative with them—paint them white and plant lavender in them or something.’

‘Imagine the look on his face!’ She snorted with pleasure at the idea. ‘Nope, I wanna get rid of it all.’ She looked at me, her eyes suddenly ablaze. ‘For over thirty years I’ve had that man’s things around the house! His bloody pictures on the wall. That ugly great armchair that doesn’t match the sofa!’

I looked around our time-capsule living room, a shrine to her years of deference, to his anger and frustration, his iron grip.

‘Where do we start?’ Like it was a cheerful, healthy task we could enjoy together.

‘I’ll do it,’ she said. ‘You’ve been such a love this week, getting everything done. But I’ll do this. You go and do some of your own work.’

I picked up my thesis from where I had stopped weeks ago, when death had set time running in all directions, and enjoyed the absorption of doing my own thing. I had so much still to do on it, and I wanted to be finished before the baby arrived, so I would have all the hours in the day just for us. There was a unique pleasure in clicking word after word into place, watching hypothesis become research, and research become fact. After a while, I managed to tune her out, getting lost in my experiment notes, the prosaic reporting of replication factors and cell cycles. Generations gave way to the next in regimented order, their linear nature an antidote to the temporal pull of the farm.

Frenzied sounds came from the rest of the house, as Mum boxed and binned items she had known for half a lifetime. I knew I should stop her—this might be some phase of grief that she would regret later—but there was something so triumphant in seeing her throw him off. It was at once manic and therapeutic, as if she could clean her way forward into a world ruled by her will.

A sudden shrill yowl ripped through the house, penetrating the little bricks of science I had been steadily laying around me. Mum’s voice rose above it.

‘Nina, help!’

My notes flew off the table as I ran outside. Mum was by the washing line, her arms wrapped around the central pole, perched on top of her upside-down washing basket. ‘Nina, help! It’s gunna kill her!’ She was pointing at Myxie, an electric ball of white static and claws, making that unearthly yowling sound, and darting forward and back at a big brown snake, which whipped and wove on the hot footpath.

‘Oh, for god’s sake Mum!’ An unexpected wave of fury washed through me, tinged with hot fear. Why was it me coming to rescue her? A quick glance and my eyes fell on a bundle of broken tools by the back door, ready for the tip. An old shovel, its blade rusty and crusted with dirt, but still sharp. I strode forward, releasing anger in vaporous trails in my wake. In one brutal movement, I sent Myxie spinning towards the veranda, a hissing, skidding muddle of legs and tail, and drove the blade of the shovel down through the snake’s neck, blood spurting as it bit through the glossy scales.

I realised I’d cried out as I’d stabbed, an athlete’s grunt of effort and triumph. In the loud stillness that followed, I felt a small rabbit’s kick of movement in my abdomen, uncertain and tiny. I put my hand down in wonder, and looked up to find my mother standing in front of me.

‘I thought Myxie was a gonna.’

‘Jesus, Mum.’ I dropped the shovel to the ground and wrapped my arms around her. ‘What are you going to do?’

‘Well you’ve killed it now, haven’t you?’

‘There’s going to be other snakes.’

‘Let’s clean this up.’ She looked down at the bloody mess on the path. ‘Remember that poem your Dad liked?’ She asked me. ‘How did it go?’ She was right, I’d recited it for him by the fireplace, after he’d come back with the snake and the boot that night, all his anger dissipated in his satisfaction.

‘I remember how it ended,’ I stared down at the slender, disembodied head and nudged the strangely light coils with my foot. ‘But never met this Fellow, Attended, or alone, Without a tighter breathing, And Zero at the Bone.’

‘That’s about right.’

* * * *

The drive back home to David seemed fast. I sped along the highway, as if I could overtake that last image of her waving. Myxie was rubbing around her feet, and the calves were milling hopefully in the top paddock. The shovel was propped against the side wall, and as the sunlight caught it, I imagined I could see a deeper red mixing in with the rust. Mum’s figure grew smaller and smaller, a straight-backed peg doll, standing proudly by her doll’s house, growing smaller, but not dwindling. My baby rabbit fluttered inside me again, little movements telling me not to worry, that the next generations would be stronger, smarter, safer than the ones that had gone before.

Erin O’Loughlin is a writer, translator and self-confessed foodie. Originally from Australia, she has lived all over the world including Japan, South Africa and Italy. Her work has been published by Leopardskin & Limes, Brilliant Flash Fiction and FTB Press. She lives in Berlin, Germany.

Lorraine McDermott lives in Melbourne, Australia and is a member of the Plenty Valley Arts Society.

She has been painting since 2005, frequently attending classes and workshops with established painters such as Amanda Hyatt, Malcolm Beattie and Julian Bruere.

She works mainly in watercolour, enjoying the challenge of mastering the techniques and unpredictability of the medium. Her favourite subjects are Australian landscapes and seascapes drawn from her experiences while holidaying and travelling throughout Australia.

Another wonderful story Erin, I love your poetic almost melodic descriptions. Even though it’s a work of fiction I still see biographical flashes- the Heyer and Sundays. Fantastic.