AN IRISH BOY IN THE BRONX

★ ★ ★ ★

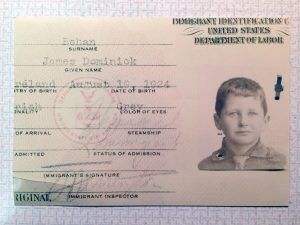

James Dominic Behan

A Boyhood in Ireland and America, 1924 to 1940

My 91-year-old father’s tales of his early years mesmerized me in my own youth—and they still do. Hardscrabble and sometimes swaggering, they conjure up times and places we won’t see again, for good and ill.

Here’s an account of a conversation Dad and I had about some of his childhood memories on April 11, 2016.

—Maria Behan

* * * *

What do you remember from your earliest years?

I was born in Lucan, Ireland, in 1924. It’s a pretty crowded Dublin suburb today, but at the time, Lucan felt like the countryside. My family was living in the gatehouse on what I imagine had been the once-impressive Behan family estate. It was a big property, supported by my grandfather’s barge business. It’s across from what’s now the Finnstown Castle Hotel. I like to think that a few generations before mine, my family had a Big House like that one. But if so, it was gone by the time my father came of age. I’m not really sure what happened.

The gatehouse was modest, as you’d imagine. It had a thatched roof and no plumbing and was basically just one big room. I lived there with my father, mother, and two siblings (one brother, two years older; and one sister, two years younger).

We had a black-and-white dog named Prince. One day as I was playing in the fields, I fell into a ditch, then couldn’t climb back up again. I was probably about three. Prince may have saved my life, barking and barking until somebody came running.

It’s funny, the few odd details I recall now, nearly nine decades on. The thing I’d most like to remember is my mother’s face. She died of tuberculosis when I was four. I tried to find a picture of her for years, but never did.

How did you come to leave your boyhood home in Lucan?

With great sadness, our father found it necessary to go to America to try to improve our family circumstances after my mother’s death. He resisted the pleas of relatives who wanted to adopt us. If my Aunt Mary had had her way, she’d have taken me in and seen to it that I became a priest, that’s for sure.

Instead, we were placed in institutions run by the Catholic Church. My brother and I were sent to St. Patrick’s Industrial School in Kilkenny, and my sister was placed in a nearby institution for girls. We never saw each other after that. Not until our dad came back for us five years later.

I don’t remember much about that time, and I don’t want to. It strikes me as a kindness that I have almost no recall of specific events. I do remember that somebody once gave me a toy, a little red car. It could have been that one of my aunts had come from Dublin on a visit. I left it on a kitchen windowsill while I did a chore, maybe washing dishes. When I went back to get it, it was gone.

What are your memories of arriving in New York?

The year was 1933 and I was nine. All we really knew was that our dad had come back to collect us. My whole world had been limited to life at St. Patrick’s, so I didn’t have any expectations about what was to come.

America was in the middle of the Great Depression, and we were moving to a small apartment in a place called the South Bronx, where my father had been living with his new wife, also from Ireland. They’d had two kids together, my stepbrothers, Joe and Larry. With the addition of my brother, my sister, and me, we became a family of seven. Our residence was a small apartment on the fourth floor of a building on 138th Street.

Arriving in America was the beginning of a new life for me.

I have one vivid memory of that first day. In the taxi from the pier to our apartment, I noticed a boy on roller skates and I thought, “Wow, what a great country! If you hurt your feet, they put wheels on them.”

How did it feel to be an Irish immigrant in America?

My brother, sister, and I all had difficulties adjusting to life in America. For a start, we talked “funny.” At school, they weren’t sure what class to place us in, since the home in Ireland operated on a very different system, focused more on religion and chores than academics. We also had difficulty eating with a knife and fork instead of a wooden spoon.

But I never felt foreign in America. To me, it seemed like everyone I knew in our neighborhood in the Bronx had come there from some other place. People spoke different languages, or at least had different accents, but they usually treated each other well. In fact, the Armenian tailor down the block bought me my first bike. He was one of the many neighbors who showed me great kindness when I was a boy.

Were you ever homesick for Ireland?

Ireland, to me, was life at St. Patrick’s. I never missed it. I was now living in America and I had no desire to look back.

Then and now, the South Bronx is a poor area. Would you say you grew up on “the mean streets”?

In the sense that everyone I knew was poor, dirt poor, yes. But despite the poverty, there was respect for law and for people who were older than you.

Life was a struggle. My dad had to feed five kids and two adults on wages he earned as a hotel doorman or later, as a porter at the gas company.

Were you expected to help out?

I did what I could to get money. I think my first job was selling shopping bags on the street. I paid two cents a piece for them, then sold them for a nickel. In those days, there were no refrigerators, so one of my other jobs was delivering ice from a street vendor to his customers’ apartments. I also delivered groceries and meat. Those deliveries earned me pennies, sometimes a nickel.

Was there a social hierarchy among the kids you grew up with?

Oh, yes. The fastest runner. The longest hitter. The guy who owned a car. They were all special people in the neighborhood.

Where did you fit in?

The answer would depend on my age. It was difficult in the earliest years, because my accent made me stand out. That alone got me into many fistfights. But as life progressed and I got a little older, I became very capable at boxing and stickball, a basic form of baseball. I was accepted then. I generally got along well with the other kids in the neighborhood, most of them the children of foreigners, or immigrants like myself.

Tell me about stickball—and some of the other adventures you had as a boy.

We played a lot of stickball on the streets of the Bronx. We used whatever was there as our equipment. Before we could get a game going, somebody would have to steal a few brooms and mops from the fire escapes on the block. We’d break off the mop or broom part to make our bat, and we’d have a rubber ball. Then we’d improvise. A sewer grate was home plate. A telephone pole would be first base. Another sewer was second. Coming back to home base, you’d have to stop at third base, which was a fire hydrant.

The East River was not too far from where we lived. We’d find some old doors, lash them together, and go out on the water. I don’t think I could swim at that time. We’d just lie on those “rafts” and drift on the river, and that was our excursion for the day. A few times, the doors came apart. I’d just hang on to what was left while the swimmers towed us into shore.

Do any dramatic moments stand out in your mind?

I’m not sure what set me off, but at one point I became very unhappy with my entire situation, so I decided to run away. I walked a long distance to the railroad yard and looked out for a suitable opportunity to board a train. Then it was getting dark, I felt hungry, and got spooked by a drifter near the tracks who was looking at me. So I went back home.

Do you have any embarrassing memories from your growing-up years?

A funny thing happened to me when I was 14 or 15. It was Halloween, so all the kids dressed up in whatever they could find. I happened to wear my sister’s skirt. I went out with the gang, and we rang people’s bells asking, “anything for Halloween?”

On this particular day, I managed to collect enough money to leave the group and go to the movies. Two movies and about four hours later, it was dark when I left the theater. I’m on the street and look down, and to my horror, I see I am wearing a skirt. It took me a long time to get home that night because I had to hide in doorways any number of times. I did not want anyone to see me.

Do you think kids today have very different childhoods from the one you had in the 1930s Bronx?

Yes, definitely. Part of it is attitude. As a kid, I would never talk back to a grownup. We respected our elders—or we’d be in big trouble.

And there’s no way that kids today would have the kind of freedom that my brother and I had to make the streets our playground, or to float down the East River on makeshift rafts. On the other hand, my poor sister was usually stuck at home, helping my stepmother cook and clean, and girls do seem to have more options today.

During my boyhood, nobody had a television or a smartphone. We didn’t even have phones in our apartments. If someone wanted to reach you, they’d call the local grocer, who’d come by your apartment house and ring your bell or knock on the door yelling, “telephone!”

Looking back, how do you think of your youth?

The early part was hard. Losing my mother; being in the home in Kilkenny; then coming over to America, where I was behind all the kids. Trying to catch up, that was the toughest part.

But once I got going, I was able to take advantage of the opportunities presented to me. I wound up doing well at school, enlisted in the Marines at age 18 to fight in World War II, went to college on the GI Bill once I got back from the Pacific, then got a job in the IBM mailroom. I worked my way up while going to law school at night, eventually becoming a lawyer for the company.

Honestly, I’ve had a great life. I think I managed it pretty successfully and I had—and have—a wonderful family.

* * * *

The black and white photos of children in New York city in the 1930s and 1940s used in this piece are by Helen Levitt (1913 – 2009). She was an American photographer who was particularly noted for her “street photography”, and has been called “the most celebrated and least known photographer of her time.”

James Behan married Mary Zabatta, a Queens girl and the daughter of Italian immigrants, in 1951. A widower since 2008, he lives in California, not far from two of his three daughters. His hobbies include golfing and line-dancing.

Maria Behan writes fiction and non-fiction. And yes, she’s a daddy’s girl.

Well done, Maria! It’s a wonderful piece of work, I see some parallels with our own family, as a matter of fact one of my childhood memories is eating dinner while my parents didn’t and wondering why the lights were not working. “Borrowing” the cup of sugar or glass of milk from a neighbour. Yes Maria, we’ve been through it, but as an extended family and on the whole we did well, huh?

With best wishes, Daragh

We did indeed do pretty well as an extended family, Daragh! Sometimes helping each other along the way. Indeed, I’ll bet you it was Dad’s Aunt Rose, your grandmother, who gave him the red car he so loved when he was at the orphanage. Sending love to you and yours…

Absolutely wonderful! Great questions and memorable replies.

A wonderful memoir, so vivid and so important to capture: best wishes to yer Dad!

Thanks for sharing this amazing account of a life. I would love to know more about the Behan family in Ireland. This was the first information that I have heard. I loved every word.

We did indeed do pretty well as an extended family, Daragh! Sometimes helping each other along the way. Indeed, I’ll bet you it was Dad’s Aunt Rose, your grandmother, who gave him the red car he so loved when he was at the orphanage. Sending love to you and yours…

Thanks for sharing this amazing account of a life. I would love to know more about the Lucan Behan family. I loved every word.

I enjoyed the story Maria. I’m planning to share with my daughters. Thanks!!

As Cousin Daragh says, our extended family has had its ups and downs, but we’re doing pretty well now…Glad you’re sharing with your girls to remind them of that!

Lucky you to have this time/conversation with your Dad! I love hearing about his boyhood, his dog Prince and his ability to move to a new country and make such a good life. I’m sure you’re whole family is glad to have this written record of his past.

Thanks, Mary! I love the stories I’ve heard over the years of your dad and mom’s adventures at home and abroad.

Lucky you to have this time/conversation with your Dad! I love hearing about his dog, Prince and his ability to move to a new country and make such a good life. It’s surprising what people have lived through. I’m sure your entire family will love having these memories written up for all to share.

So great Maria! What a great conversation! I like the part where he would float around on old door rafts in the East River!

Maria, I find this so moving. As the story of your dad but also the context it gives me for you somehow. What a wonderful thing to do to document your dad’s story…. I wish so much I’d done it with my parents. Xxxxx B

Thanks, B! The idea came from The Wild Word’s wonderful editor, Kusi Okamura, who knew something of my dad’s history, and I’m so glad she asked us to do this piece. And my dad’s delighted with the final piece, including the way Kusi presented it. Because this material is so great as a family archive, I think I’ll forge ahead and see if I can get him to do a follow-on interview covering his time in World War II and then meeting my mom and starting a family.

Jim:

Today is lApril 11th, and I’ve just read the story of your life. It’s unbelievable that I found such an article by chance. I was looking up to see of Ilona was still alive, she isn’t, unfortunately, and so decided to look up other people.

I hope you’re still enjoying yourself out there in sunny California.

We are still here, however, Charlie is not well. We now have a two-year old grandchild who gives us very happy times. Christian picks him up from nursery school at night and stops here for a little visits. It makes our day.

We hope you have a Happy Easter, and I’ll write more soon.

Love to you and alleged amity.

Evelyn

Aunt Evelyn! Lovely to find you here! I’ll pass along word to my Dad when we’re together for Easter. Sorry to hear about Uncle Charlie. We’ll give you a call in the coming days to say hello… —Maria

Molly

I had the pleasure of meeting Jim Behan at Spring Lake Village, where we both reside in Santa Rosa,Ca.

Today we had a lovely conversation and he shared his website with me. I loved the story. He reminds

Me of my fatiher in law who had an incredible sense of humor and a love of people, no matter what their

Station in life.

THANKS Jim

Hello Jim! I was with you last night at the SLV hall party and enjoyed talking with you. You told me about this article about your life that your daughter wrote, and I looked it up this morning. I really enjoyed it and am always amazed how some children survive such difficult times. Good for you to make a good life for yourself and your family. Thanks for telling your story

Sincerely, Carolyn Miller Apt. H208

Hello Jim! I was at the SLV hall party last night and i enjoyed talking with you. You told me about this story that your daughter wrote about you and I looked it up this morning. I enjoyed it very much and am amazed how many children like you manage to rise above a difficult childhood. You have made a good life for yourself and your family and I am impressed. Thank you for sharing your story.

Sincerely, Carolyn Miller Apt. H 208

A beautiful piece, Maria. It opens up a whole new window into the life of your dad and my wonderful godfather. Such an astonishingly brilliant thing to do: to sit down with your dad and have some quiet and reflective moments with him; his recollections came easily, fluidly, and even poetically. A treasure, this.

I have the wonderful pleasure of working at Spring Lake Village where Mr. Behan currently lives, and without a doubt, he is one of best men that I have ever met in my life. The playful enthusiasm that permanently resides within him, easily spreads joy to everyone he comes in contact with. When he speaks, I find myself reverting back to a child, listening to a bedtime story. Hanging on to every word as if my superhero is going through another adventure. It is easy to gravitate to such a man with the care and compassion that he shows for others. He is humble and generous, willing to give his time to anyone in order for their day to be better. It has truly been an honor of mine to serve this man for the past 9 months and I look forward to many more memories. I would like to thank the author for taking the time to write this interview and share it with the world. He is a daily inspiration, a role model and, during a very dark time in my life with not much to be thankful for due to the pandemic, he is the best part of my day. The world could use more James Behan’s. Thank you!

On behalf of Jim Behan’s daughters, we truly appreciate your comments. It’s very comforting to know that our father was cared for by such a kind and compassionate person — and someone who “got him” and could appreciate who he truly was. Thank you for your thoughts

Jim is one of our residents at SLV that will always try to make our jobs easier for us. He is a true gentleman, always pleasant, and has a charming sense of humor and a cool and calm demeanor. He is a perfecr example of the generation that has class, civility, and a big heart. See you on our next trip Jim and thanks for the link.

Just read this amazing story of an American success story. I live at SLV also and nightly meet up with Jim going to or from dinner. Jim’ prodly wears his Marine Corp cap having spent 19 months in the Pacific during WWII. His story is a beautiful explanation of those that are called the greatess generation, a well deserved designation. I believe his service in the Corps would be an equally riveted description but understand – I have never one of those heroes who wants to talk about. Semper Fi Jim

Many people fail to realize that most of BX was very IRISH .

Clason point – FERRY POINT PARK & lots of east Tremont av.

South BX.

WEBSTER AV

UNIVERSITY AV

BAINBRIDGE AV

NOW THE LAST HOLD OUT * KATONAH AV.

Many people fail to realize that most of BX was very IRISH .

Clason point – FERRY POINT PARK & lots of east Tremont av.

South BX.

WEBSTER AV

UNIVERSITY AV

BAINBRIDGE AV

NOW THE LAST HOLD OUT * KATONAH AV.