ARTIST-IN-RESIDENCE

★ ★ ★ ★

JOHN O’LOUGHLIN

THE STORY OF THE BURNT POT

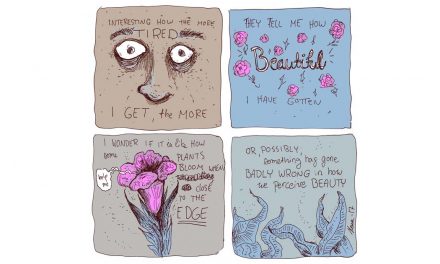

Sue’s friend telephoned her on a hot windy day last December to tell her ‘Sue, you have to get out of your house and head for a safer zone. There’s a bushfire raging in your area!’ Sue was inside her house at the time, no radio switched on and oblivious to what was happening outside. She left straight away. A half hour later her house was gone. Totally burnt to the ground by the bushfire, along with a number of others in the village. Sue told me that only one item remained intact in the burnt-out house: one of my pots that she bought from the Ballarat Art Gallery. Everything else that she owned was gone, burnt to ash.

You can only imagine the distress of Sue and her family at losing everything, but she is back at work and getting on with life. Today I was privileged to see the one remaining piece of her household goods, the pot. The bushfire was so sudden and so hot that it burnt away at the surface decoration of the pot. As the fire consumed all of the oxygen in the air it created the perfect ‘reduction atmosphere’ in the house (now a kiln), and it turned the copper oxide on the clay to red.

The little pot has a grey and reddish finish with some carbon blackening. It speaks to me now so much more than it did originally. Nature has applied it’s own finish to the piece, in a violent and vicious attack that destroyed everything but the piece of stone previously moulded by fire. The pot has been through the fires of hell but is not destroyed. The trauma has rendered it more fragile but now it is admired and wondered at in the regional Art Gallery where Sue works. A true wonder of nature, if we weren’t so mad at nature for her destructive whims.

John O’Loughlin

This is a photo of the pot and of its partner, as I made two pieces at the time.

I have given Sue the partner piece.

FIRE

Fire is such a primal thing. I am awestruck when I am firing the kiln, amazed by what is happening inside this big oven, at the dramatic change that is taking place in there. The wood kiln firing is the most dramatic, a long tunnel of a kiln and when the fuel is tossed in the flame roars out of the chimney into the sky. This is dramatic and symbolic, especially when one is doing a night shift as a kiln ‘rat’. I can’t help imagining what is going on inside the fire chamber, with wood ash rising and flowing with the flame, showering and glazing the pots.

The raw clay is fired to 980°C, becoming a soft stone that can be safely worked with to glaze and finish. Stoneware clays will stand being fired to very high temperatures. My work is best fired to 1222°C, or can go to 1310°C. In a wood-fired kiln the temperature can reach 1400°C.

I can hardly bear the three days of cooling time before the wood kiln can be opened, and then the unpacking and looking at all the pieces. They are laid out on the grass in the same position they occupied in the kiln so that the effect of fire and flame can be evaluated. I love the wood fire. I don’t have much access to this kiln so it is very special. The fire is an agent of change. The dull grey clay pot goes into the kiln, but when it comes out it can be a thing of great and unique beauty.

CLAY

I love the clay between my hands, soft but firm as it rises to the touch, blooms outward or inward according to my desires. I enjoy hand-building my “Reliquary” forms from slabs of rolled clay, pressed into one of moulds that I have made. I join the slabs to make sides, bases and lids, embellishing the vessel to give an over-decorated baroque feel to it. I am very content and completely absorbed when I am working in the studio.

Every potter has their own unique decorating style. Mine is to use a combination of engobes, oxides and glazes. Mine use a lot of bone ash to make it crackle and crawl, giving it an ancient feel, like a piece from an archaeological dig. This ancient feel is enhanced by the gas kiln firing process called ‘reduction firing’. This produces the wonderful copper red colours that the ancient Chinese discovered, or soft pinks or greens depending on the fire and heat.

I love the softness of clay, its infinite mouldability, its attention to the softest touch of a shell or a piece of sawn timber or a crease in a mould that leaves the finest of impressions on the surface of the clay. When I impress a thin slab of clay in a mould and lift out the informed piece, a perfect representation of the original, I get excited. I stay excited for the piece until it is through the decorating and firing processes and sits before me as a successful piece of pottery. Then I am satisfied.

For more on the art of John O’Loughlin and his artist residency at The Wild Word, click on button to go to the Artist-in-Residence page.