MAKING A STAND

★ ★ ★ ★

Image by Ashling McKeever

By Clare Lanigan

Growing up in Ireland, you learn to read silence. The space between words and the things left unsaid are full of messages that people who grow up here learn to infer and interpret. We all do it—it’s a hard habit to unlearn.

Part of that habit involves learning to read subtle messages about social class. Historically, respectable middle-class families were never, could never, be openly pro-choice. At the same time, the stigma against single mothers—that same stigma that sent girls to Magdalene laundries and as late as the 1990s meant single mothers were avoided by some neighbours—was communicated clearly and unequivocally. Only certain types of girls do that. Fertility could be negotiated, respectability could not. A short story written by Brendan Behan in the 1950s, The Catacombs, centres around a party held by a middle-class Dublin family to celebrate their daughter returning from England after an abortion. The reason for Deirdre’s absence is only barely alluded to in the conversations among the family members. They’re just relieved to have her back to “normal”, to have the status quo restored.

Since 1983, a constitutional amendment, the 8th amendment as it’s known, states that a pregnant woman and the embryo or foetus in her uterus have equal right to life. The aim of this amendment was to prevent legal abortions ever happening in Ireland. In that regard, it was, and still is, successful. Irish women had abortions before 1983, and they continued to do so after 1983, by travelling the short distance to England (not Northern Ireland) and availing of services there. The many groups that initiated the 8th amendment campaign did not lobby for pregnant women seeking abortions to be imprisoned in Ireland, especially after the PR disaster of the famous X case (a landmark Irish Supreme Court case which established the right of Irish women to an abortion if a pregnant woman’s life was at risk because of pregnancy, including the risk of suicide). They simply did what most of Irish society did and still does—exported and then ignored the issue, unless it threatened to return to our shores.

Growing up, I was aware of the injustice, but shut myself off from thinking about it too much. The topic was invisible in the political sphere. There was an assumption that the proximity of England made the issue moot. And what was the point of protesting anyway? I already felt that protesting didn’t do anything. Most of the formative political events of my youth seemed to centre around people lying, which cemented my already pessimistic tendencies. The revelation of years of child sex abuse and cover-up by the Catholic Church. The 2003 invasion of Iraq under blatantly false pretences. As far as I could see, trying to change things was a fool’s game.

The issue that made me change my political consciousness was nothing to do with abortion, but in retrospect it tied in with the greater cause of social justice. The financial crash of 2008 and subsequent austerity politics were pretty catastrophic for Ireland. There had always been homelessness in Dublin but from 2010 onwards the number of street sleepers increased dramatically. Suddenly my walks through town became marked by the sight of countless huddled forms in sleeping bags. Others tried to deny the humanity of these people—dismissing them all as selfish drug addicts who couldn’t be helped anyway—but their sheer visibility was a beam in our collective eyes. I had heard of and even shared prejudices towards marginalised people in the past, but this was too much for even the most self-involved late-twentysomething to ignore. Slowly, I began to become politically aware. Actually converting that awareness into action took a couple more years. For some time, I thought about volunteering with homeless charities, but I didn’t have the emotional robustness to deal directly with suffering in that way. I felt cowardly, but knew my limits.

In 2015 the marriage equality referendum was held in Ireland. While it’s now (already!) looked back on nostalgically as a magical time where the country pulled together and celebrated love, in reality it was a pretty traumatic experience for LGBT people, who were expected to politely beg for human rights in media debates dominated by aggressive and slanderous Catholic right-wing pundits. Meanwhile, the consensus among “respectable” Ireland was that the advocates for equality were not being “respectful” enough to those spitting hate in their faces. In the end, the landslide victory was chiefly won by the votes of those largely ignored by the mainstream campaign. Almost immediately after the referendum, people on social media began to talk about repealing the 8th amendment, and the #repealthe8th hashtag initiated by the Abortion Rights Campaign (ARC) began to gather strength. Some months later, I joined ARC, and began attending meetings.

There’s a lot of power in declaring where you stand on something. By nature as a young middle-class woman, I was never much inclined to “make a fuss” about things. For too long, I accepted as normal the fact that the State of which I’m a citizen had control over my body and that of other women. For many, it’s easier to continue that acceptance. But for a growing number, it’s not.

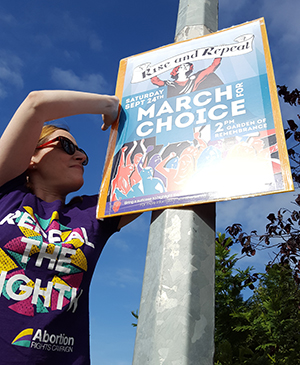

Joining the Abortion Rights Campaign and actively openly stating my support for repealing the 8th amendment and campaigning for free, safe, and legal abortion in Ireland symbolises my personal evolution from believing things can never change to believing they can. It symbolises my rejection of respectability politics, of accepting the status quo—not just in regard to abortion rights, but to social justice in general.

Despite the flaws of its campaign, the marriage equality referendum genuinely gave hope to me and many other Irish women that injustice is not intractable and change is possible. As well as giving me the courage to stand up for bodily autonomy—mine and that of the thousands of others who are denied it by the 8th—being part of the movement for reproductive rights gives me a sense of meaning I never had before, and never knew I needed.

There’s a long fight ahead, but this time I’ll be part of it.

Clare Lanigan is a history nerd who at the slightest prompting will tell you everything you didn’t realise you needed to know about gender roles in the ancient world. She lives and works in Dublin, and is a volunteer with the Abortion Rights Campaign. Follow on Twitter @clarelanigan

Trackbacks/Pingbacks